Temporal / Reclamation

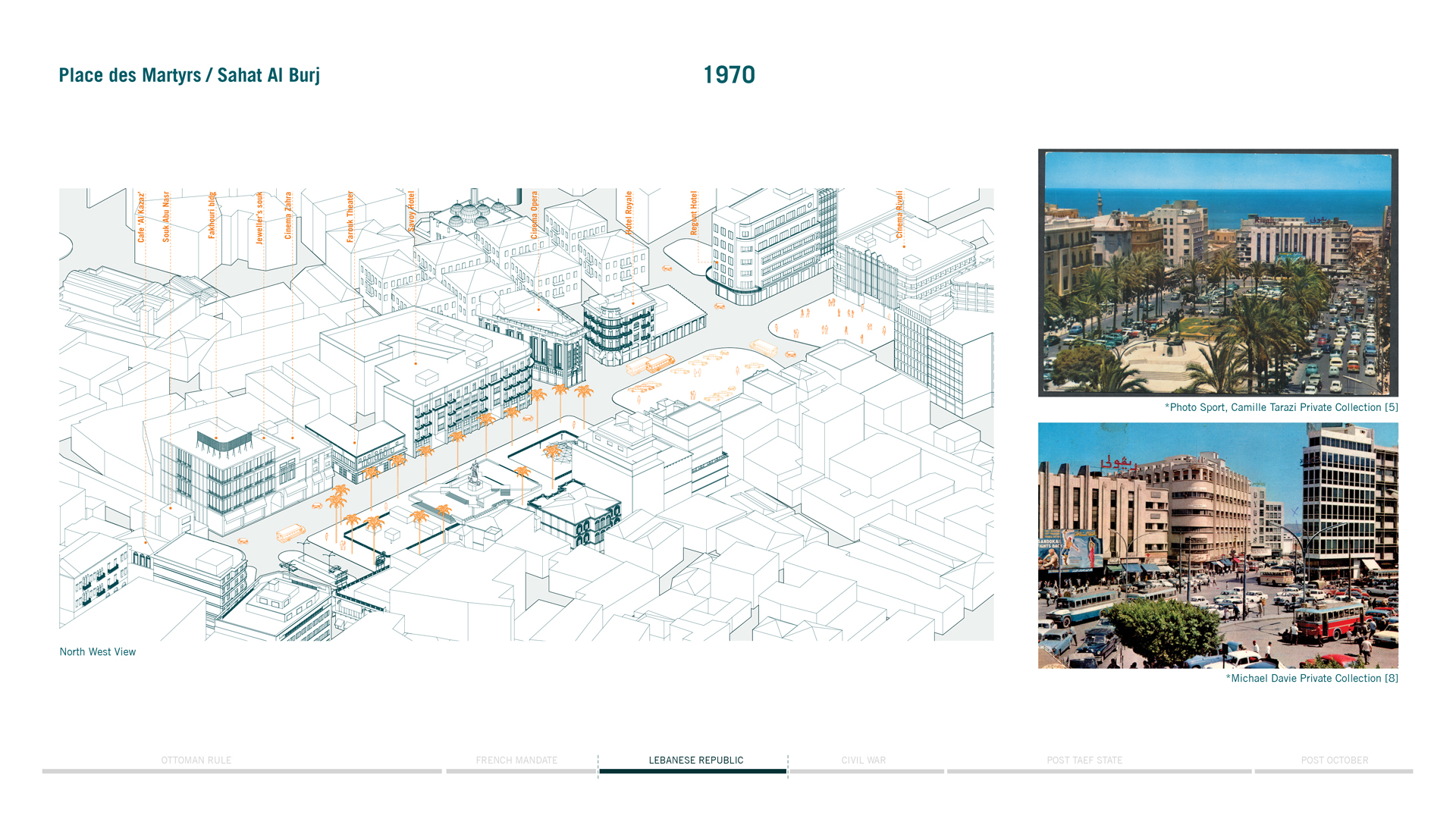

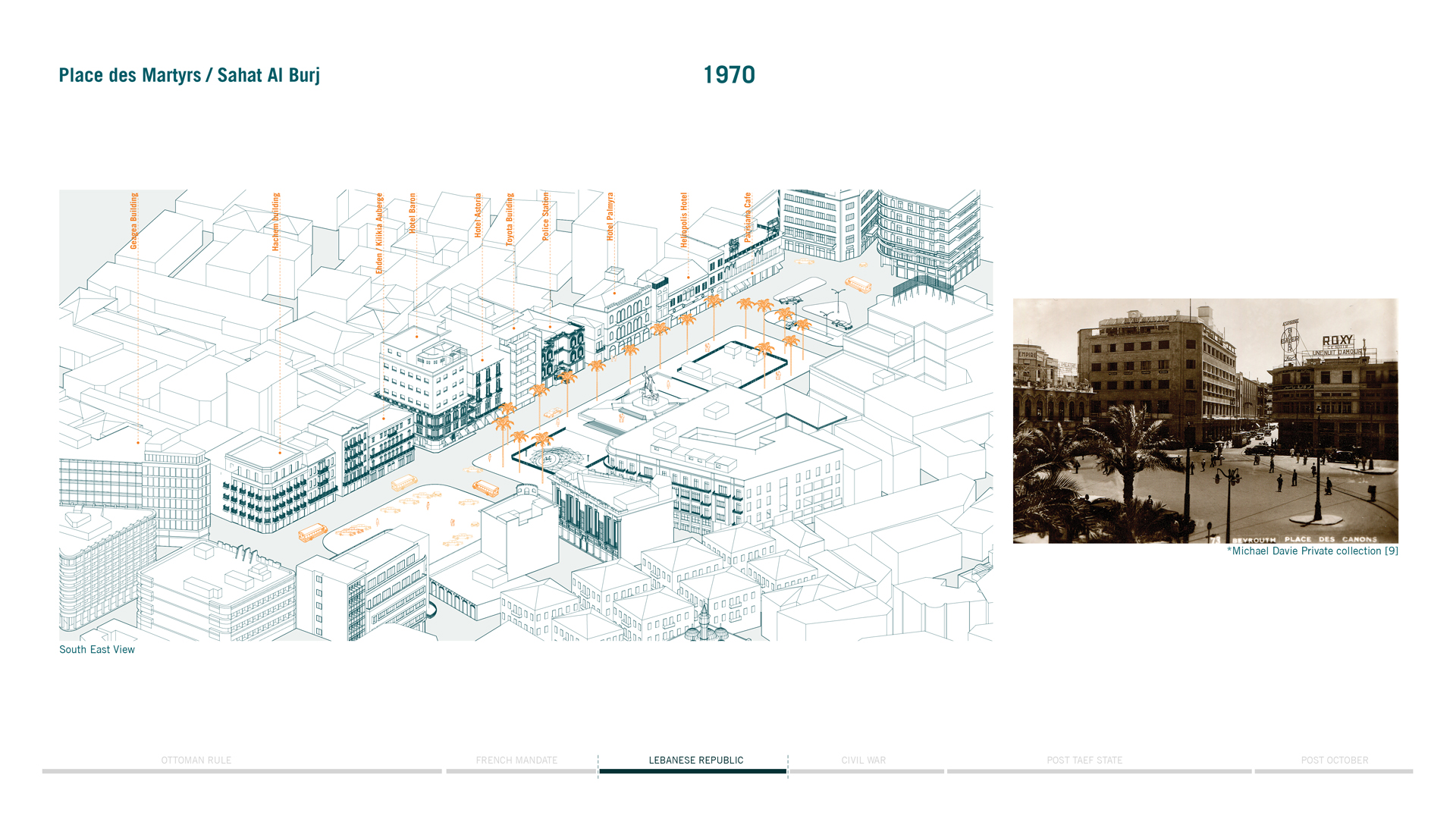

The Temporal lens focuses on the metamorphosis of Martyrs Square, Beirut’s collective space, through the ages, narrating its spatial history and ground manifestations through visuals, and archival photographs. Using a methodology of mapping, extensive photographic analysis, and detailed 3D modeling, the square’s transformation is reconstructed in 11 time periods, simulating its lost urban history.

The project looks at the ground through time, unfolding the genealogy of the city's prime space- Martyr Square- the fluctuation of its identity, urban form and public appropriation since the Ottoman period until the present. It traces its evolution to become the nation's space of appearance, foregrounding how its ground allowed the different communal expressions throughout its historic lineage. The work also considers its recent reclamation during the 17th October revolution as a creative act of commoning and a valuable lesson in collective city making.

The Temporality of Martyrs Square

Martyrs square, a symbolic space in the heart of Beirut, has always had the capacity to shape a local collective. Through the ages, the square in its drastically changing forms and names, has proven to remain the people’s central space of urban, social, and political reclamation. The continuous erasure of its built fabric has formed its identity and solidified its symbolism and significance. Through this work, we reclaim this spatial memory, reconstructing its faded spaces, walls, and events, as a necessary act towards moving forward.

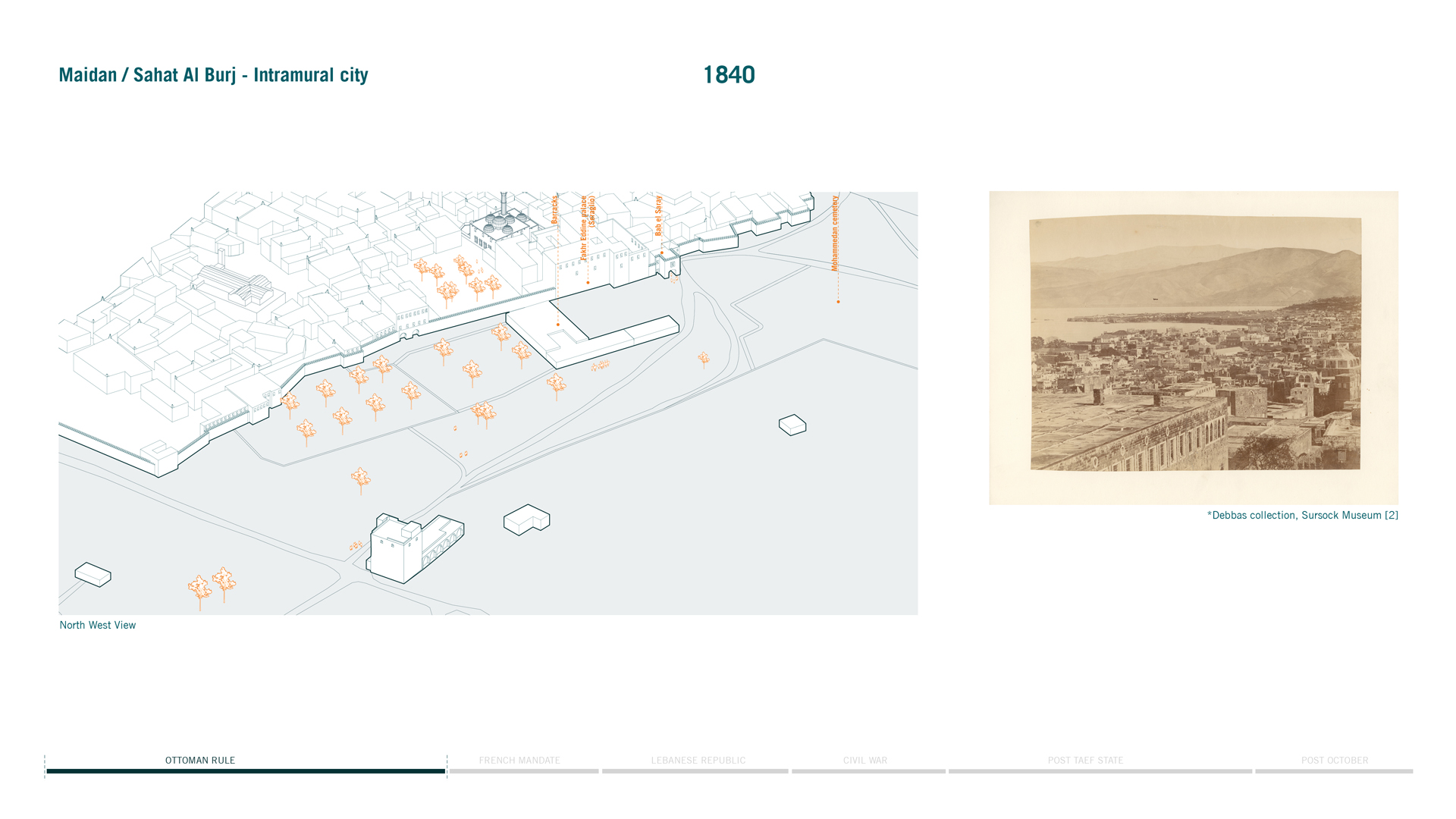

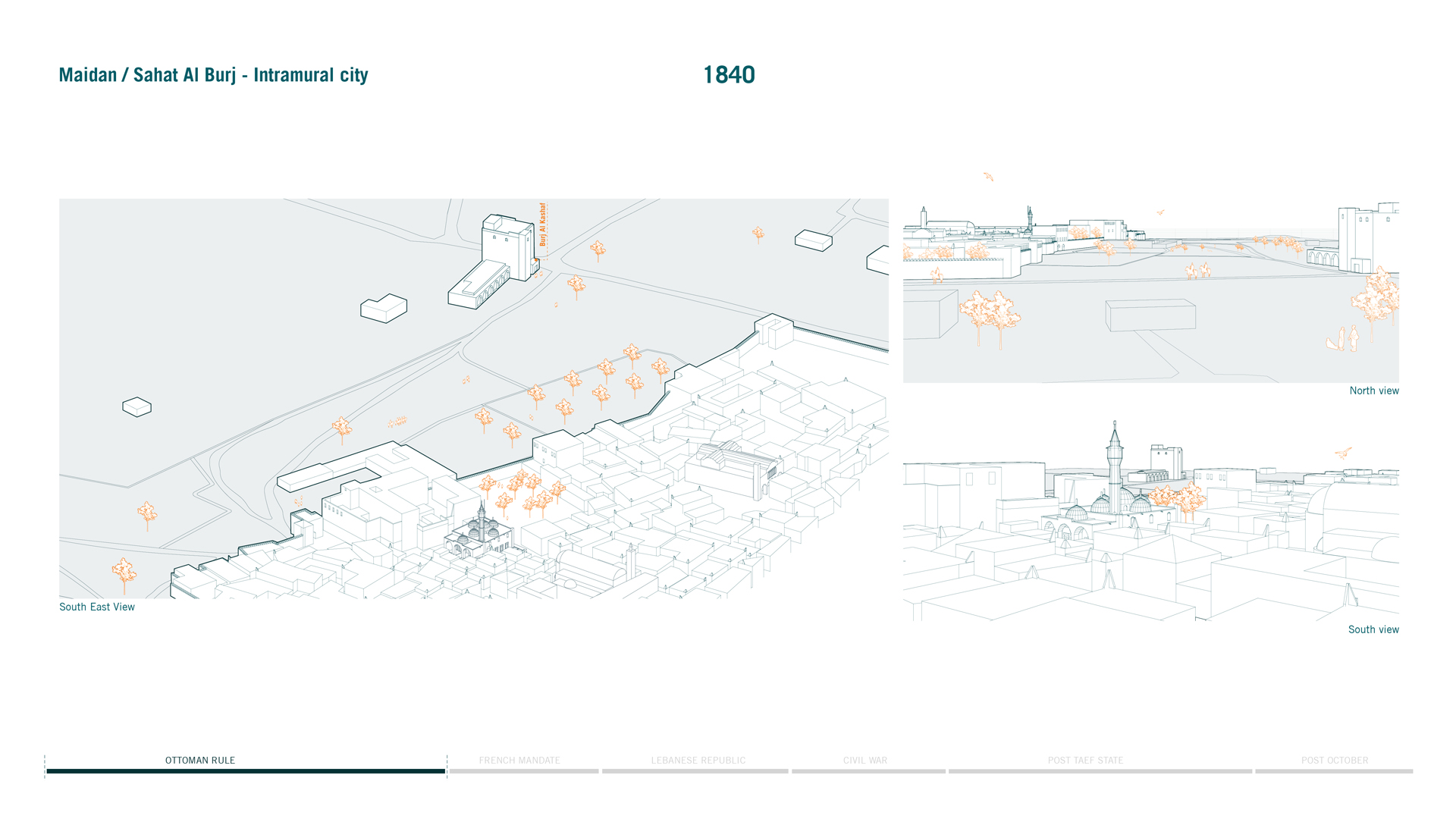

North West axonometric – 1840 to 2019

In order for us to live together, we must remember our spatial history, and how we lived, loved, fought, laughed, and survived together. So that we never forget again

Spatial Metamorphosis of Martyrs Square

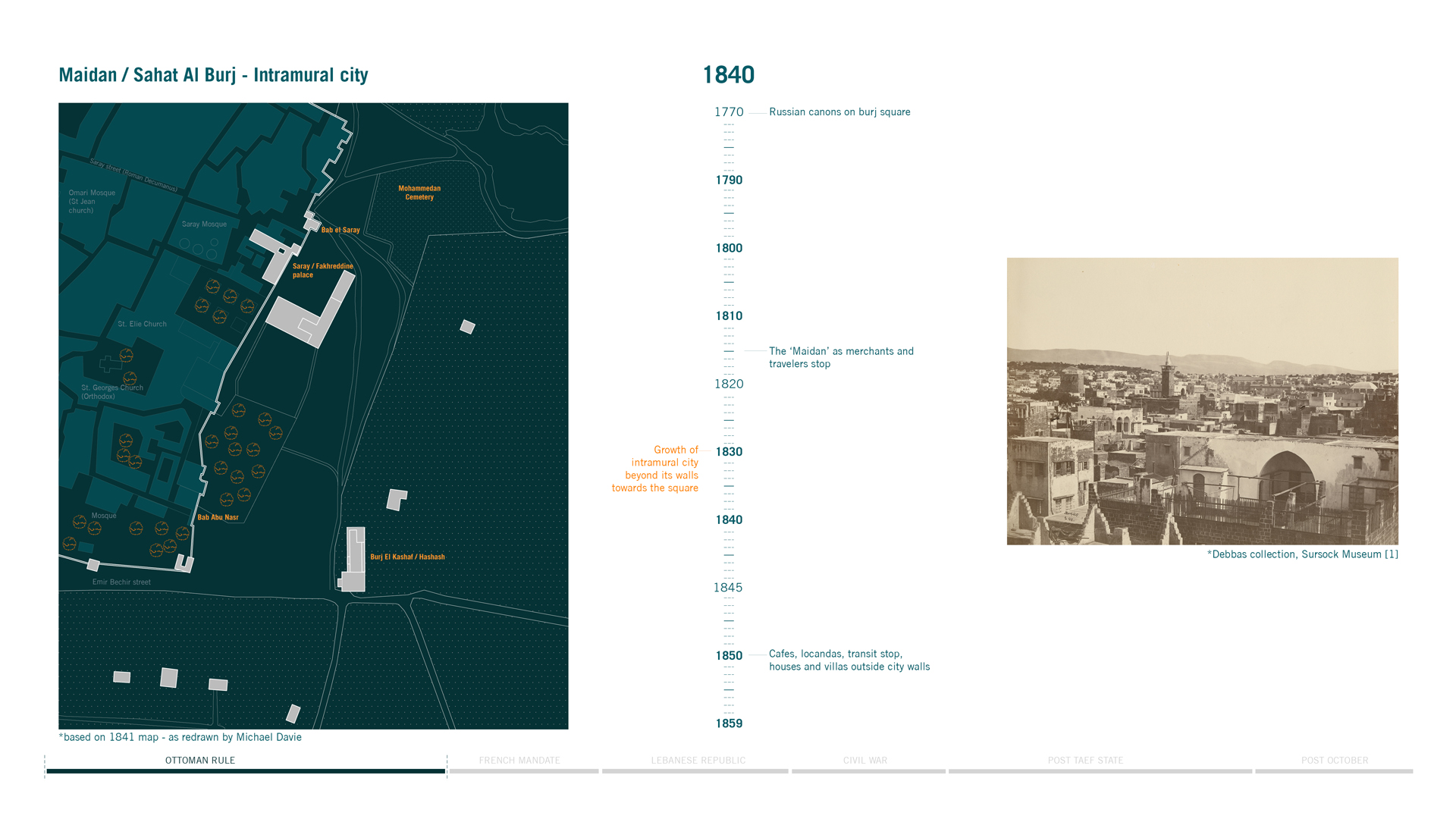

1840 - Maidan / Sahat Al Burj - Intramural city

The square in its earliest form was a free space, an open field to the east of the intramural city’s fortification walls. With its watchtower, Burj el Kashaf, naming it as ‘Sahat al Burj’, the open field was as a military training ground and the occasional traveler’s stop, a gateway to the city from the east. On the eastern hills, houses amid orchards rise, after the city started to grow out of its walls in 1840. On its eastern walls, a main gate ‘Bab Al Saray’ allowed entry into the old city, flanked by the Emir Fakhr Eddine Palace (Seraglio).

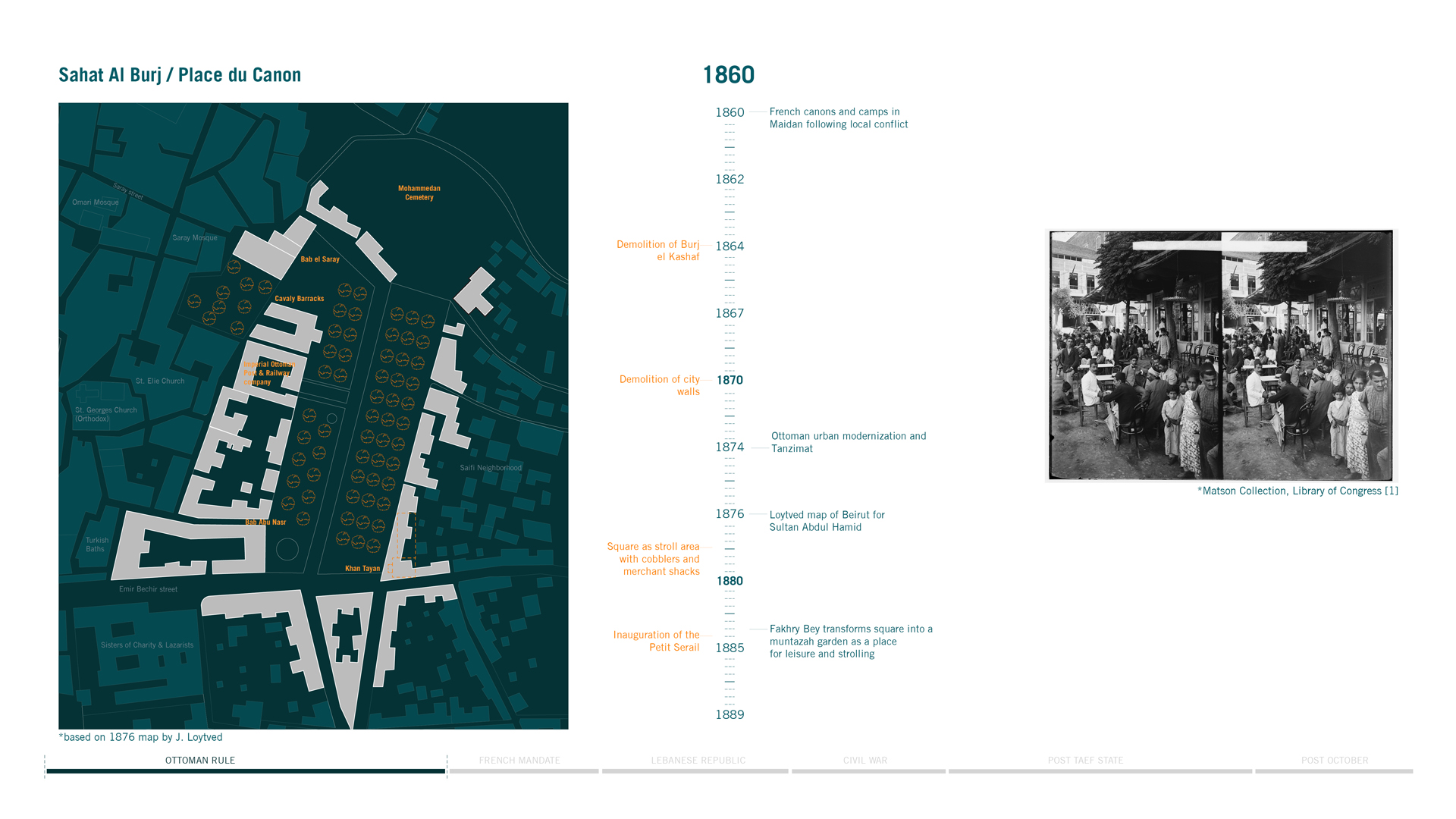

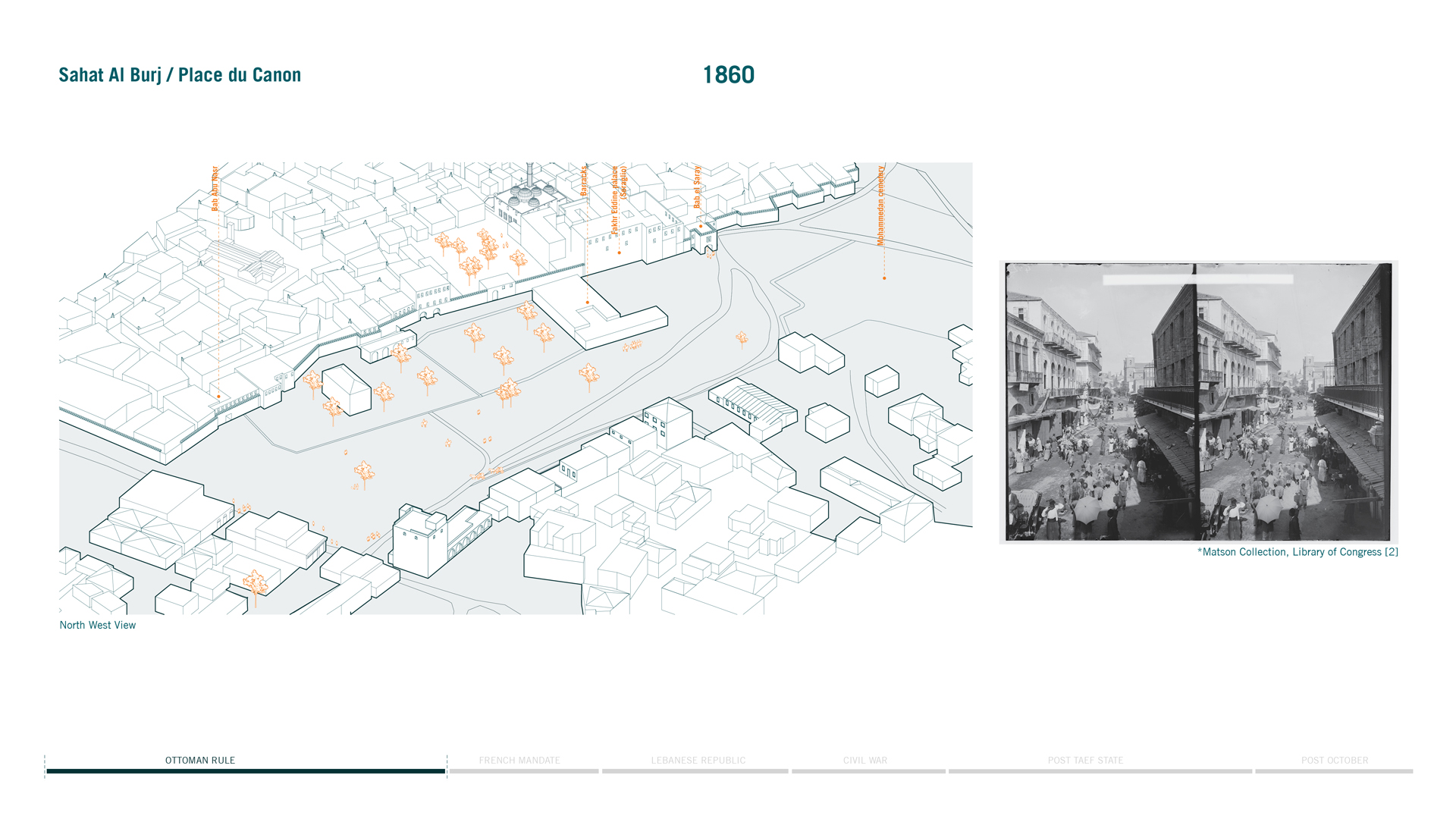

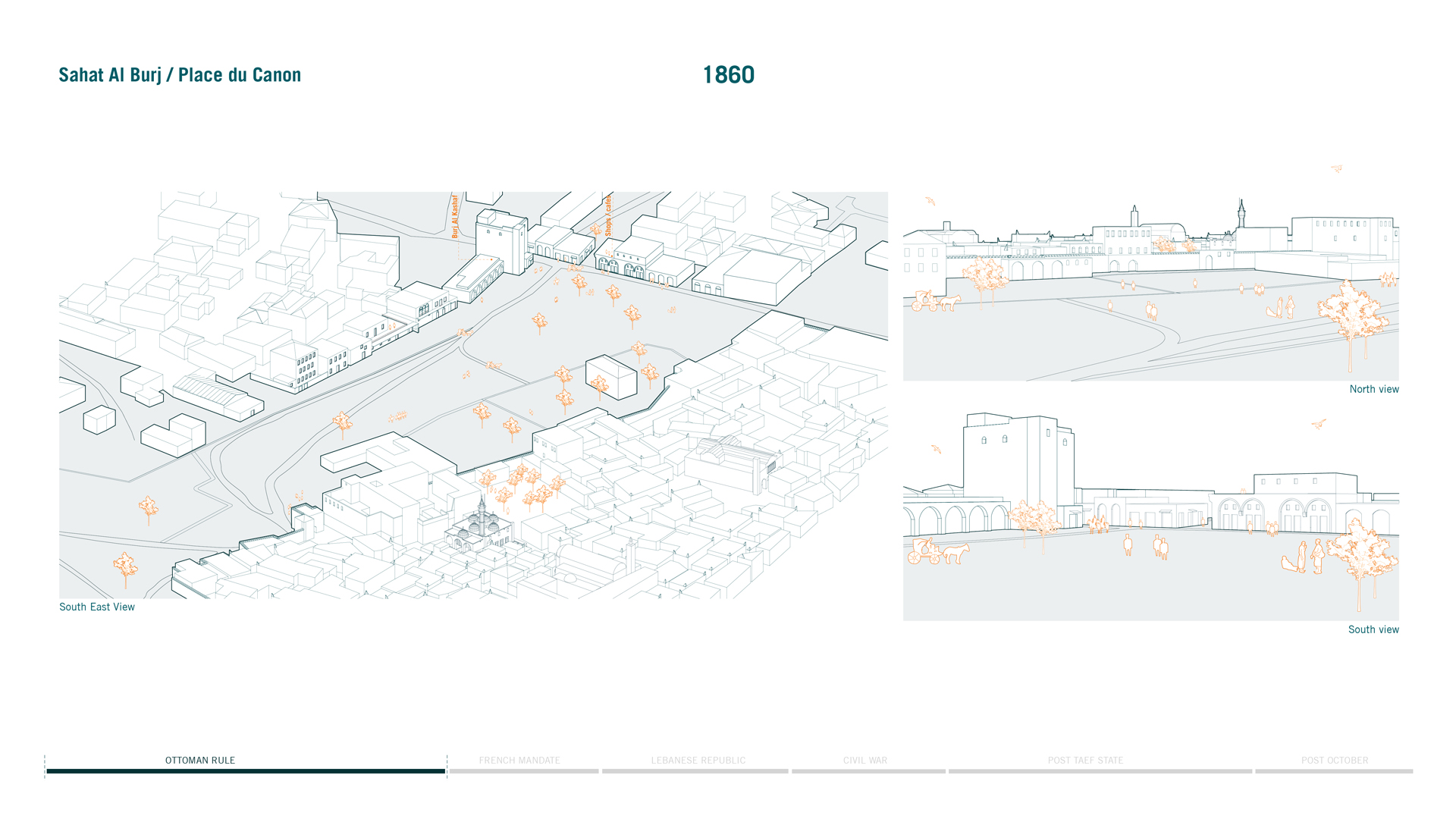

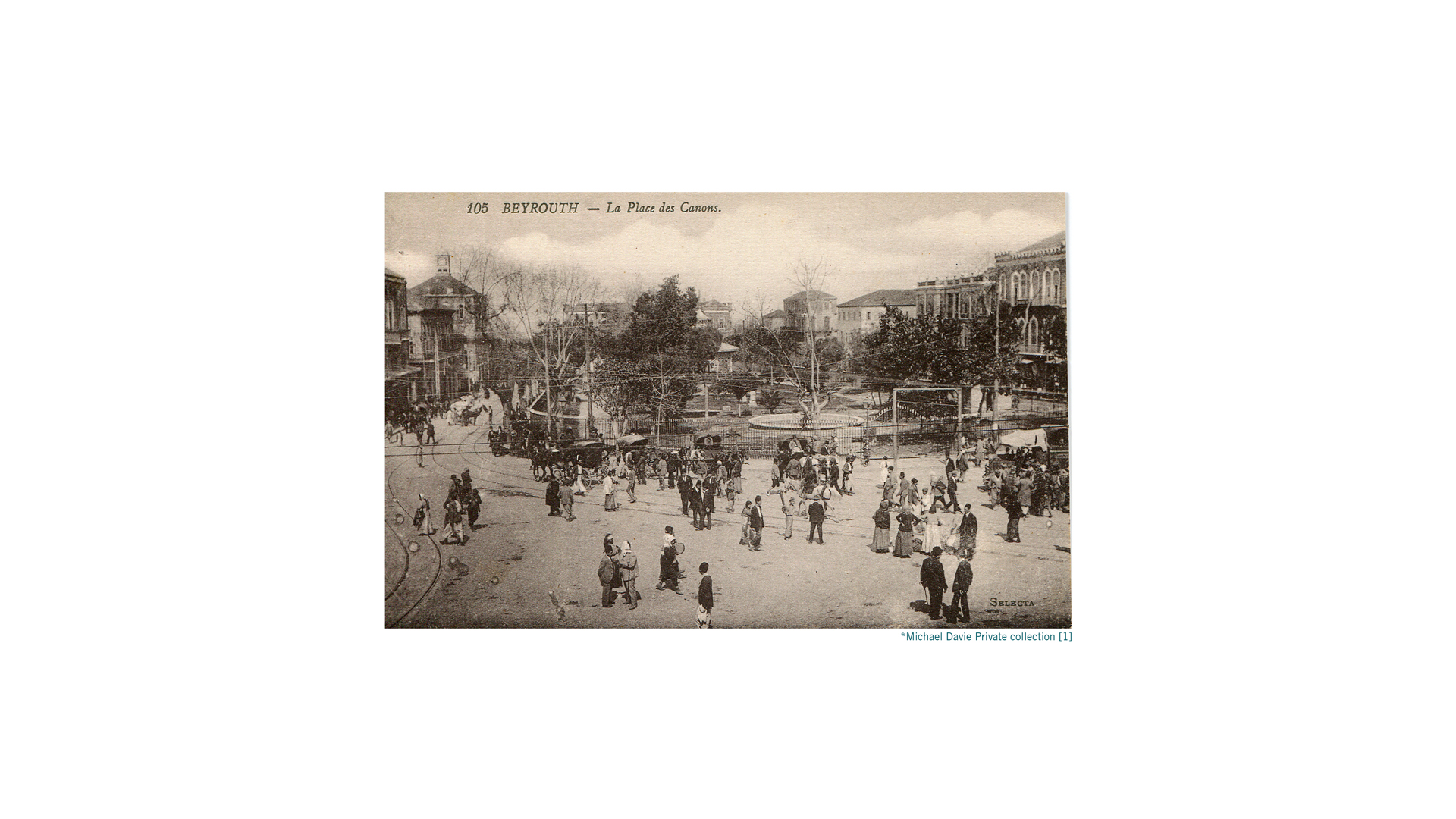

1860 – Sahat Al Burj / Place du Canon

By the 1860s, the field had already transformed into a vibrant space with shops, French run cafes, locandas, and houses and villas outside the city walls. Its location made it a vital transport and trade node, linking southward to Damascus and northward to the port of Beirut, by way of caravans and omnibuses. During this period, ‘Burj el Khashaf’ was demolished, although its name still remains attached to the square today. It bore a new designation however at the time, Place du Canon, as a result of French canons deployment in 1860, interfering to end local massacres in Mount Lebanon.

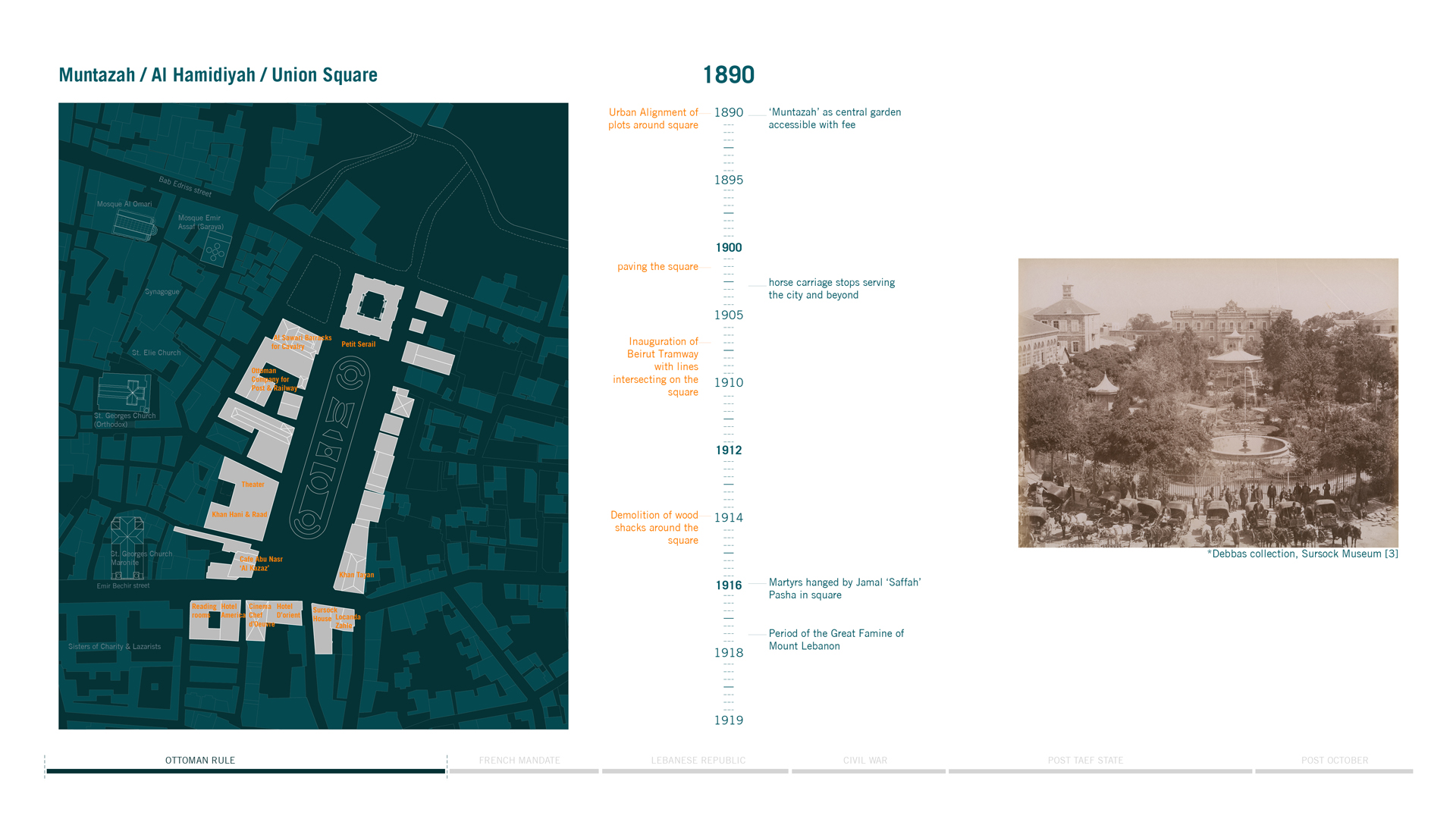

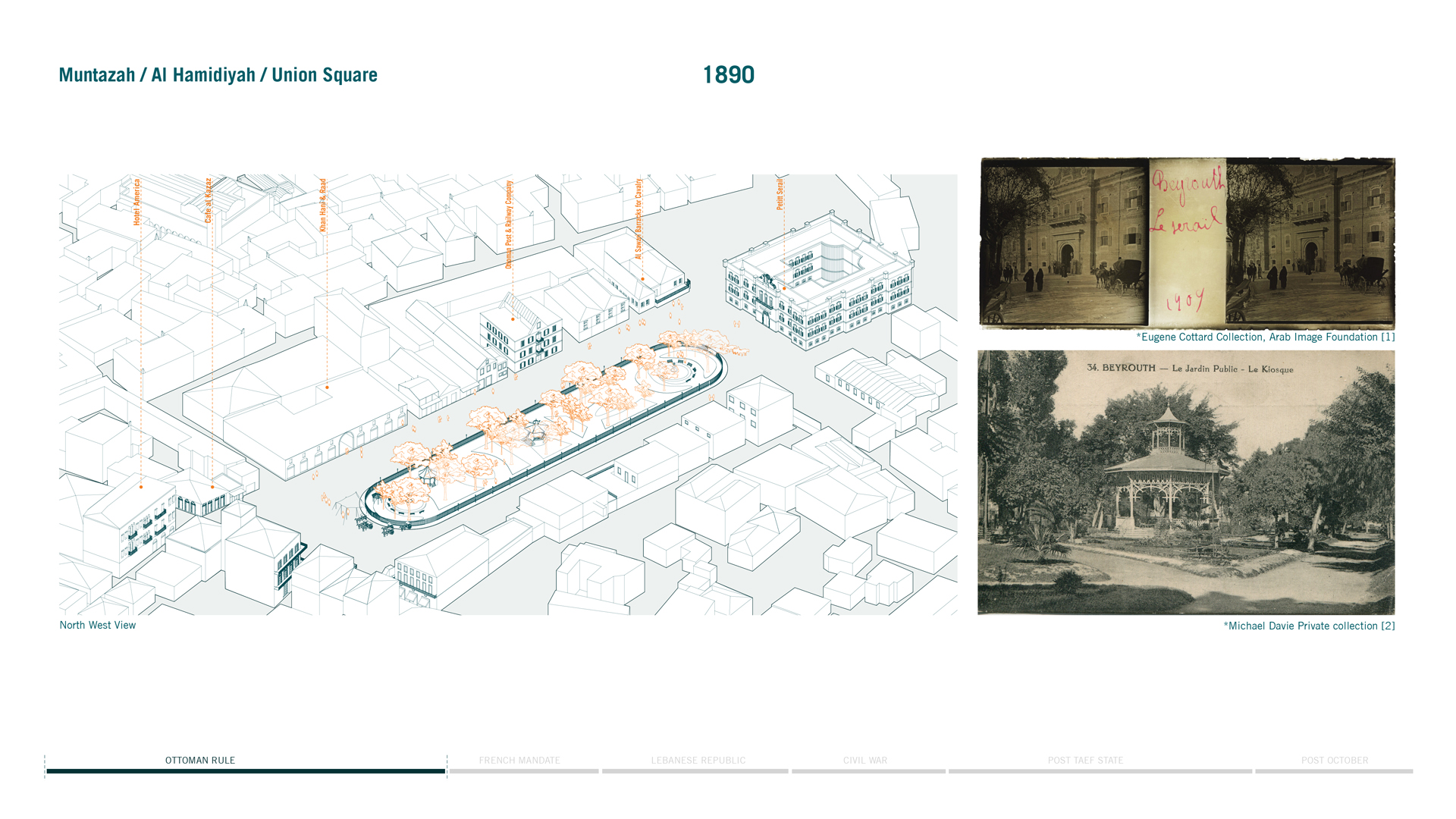

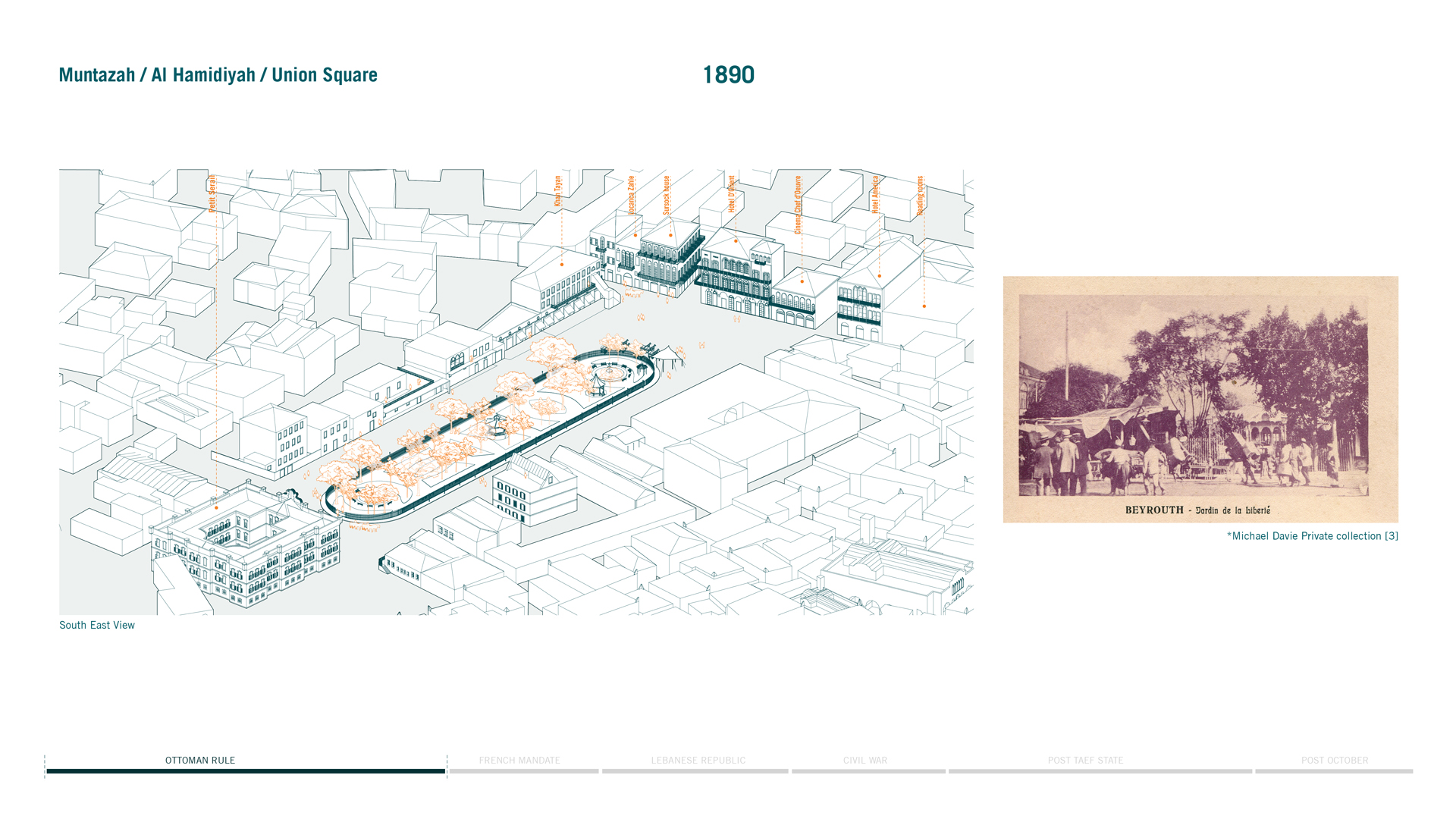

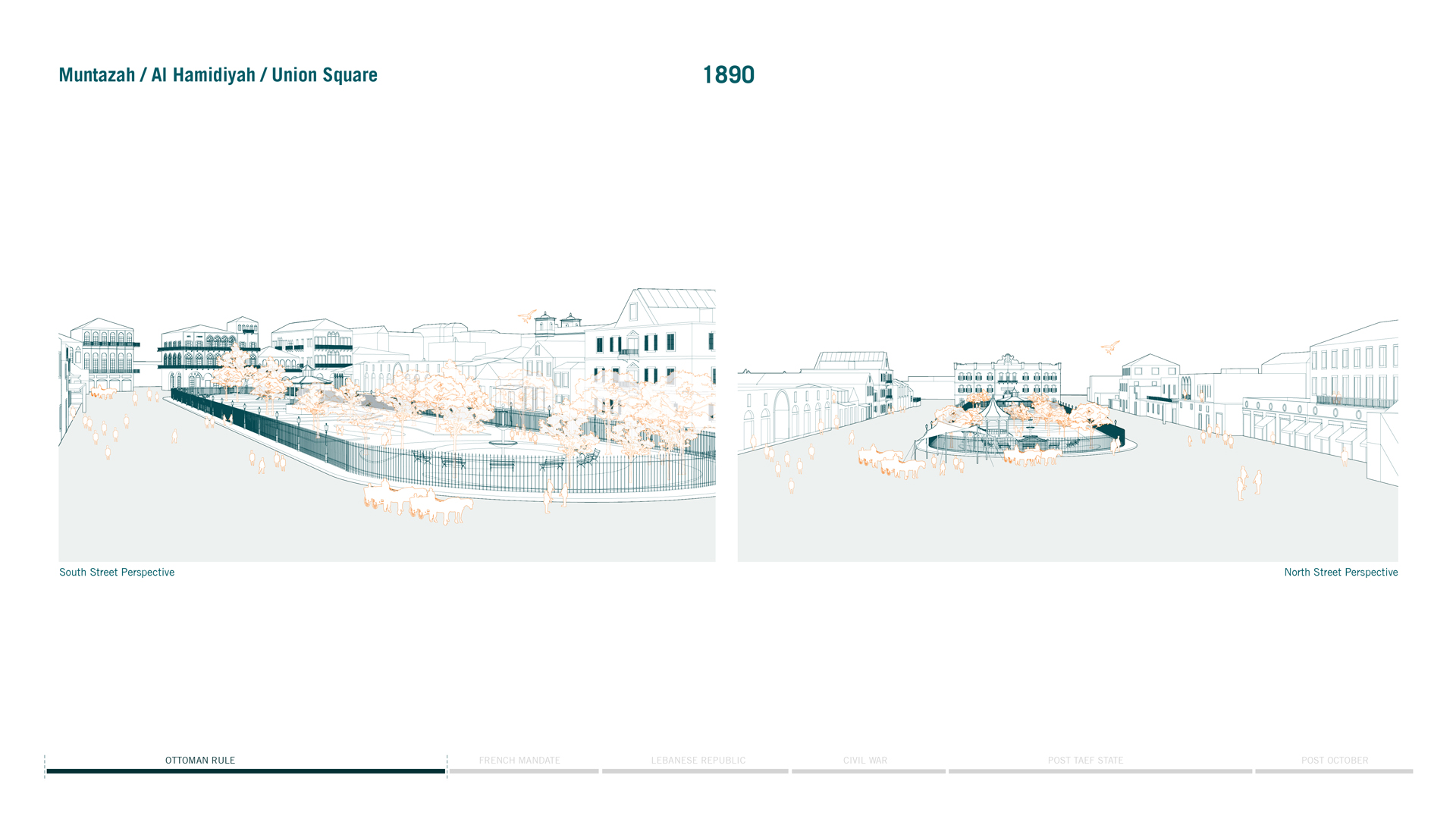

1890 - Muntazah / Al Hamidiyah / Union Square

During a period of Ottoman urban and infrastructural development (Tanzimat), the city rapidly grew in population and urban density outside its walls, with the square spatially forming as a closed and central urban space. Beirut governor advanced the redesign of the square as a garden for leisure (Muntazah), with an iconic government building at its northern edge, the Petit Serail. The period witnessed the Great famine of Mount Lebanon and the hanging of local martyrs on the square, sealing its designation as Martyrs’ square.

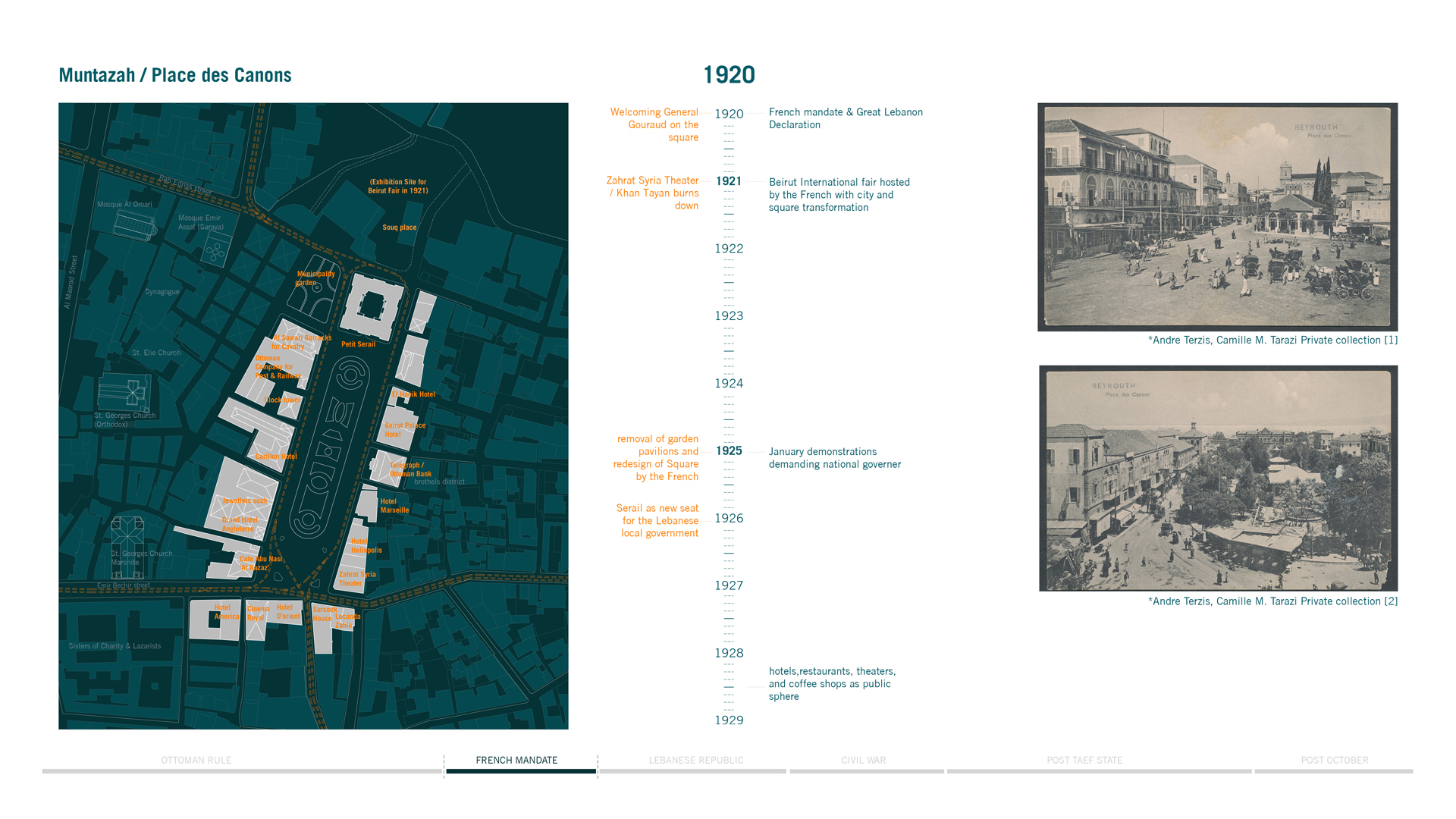

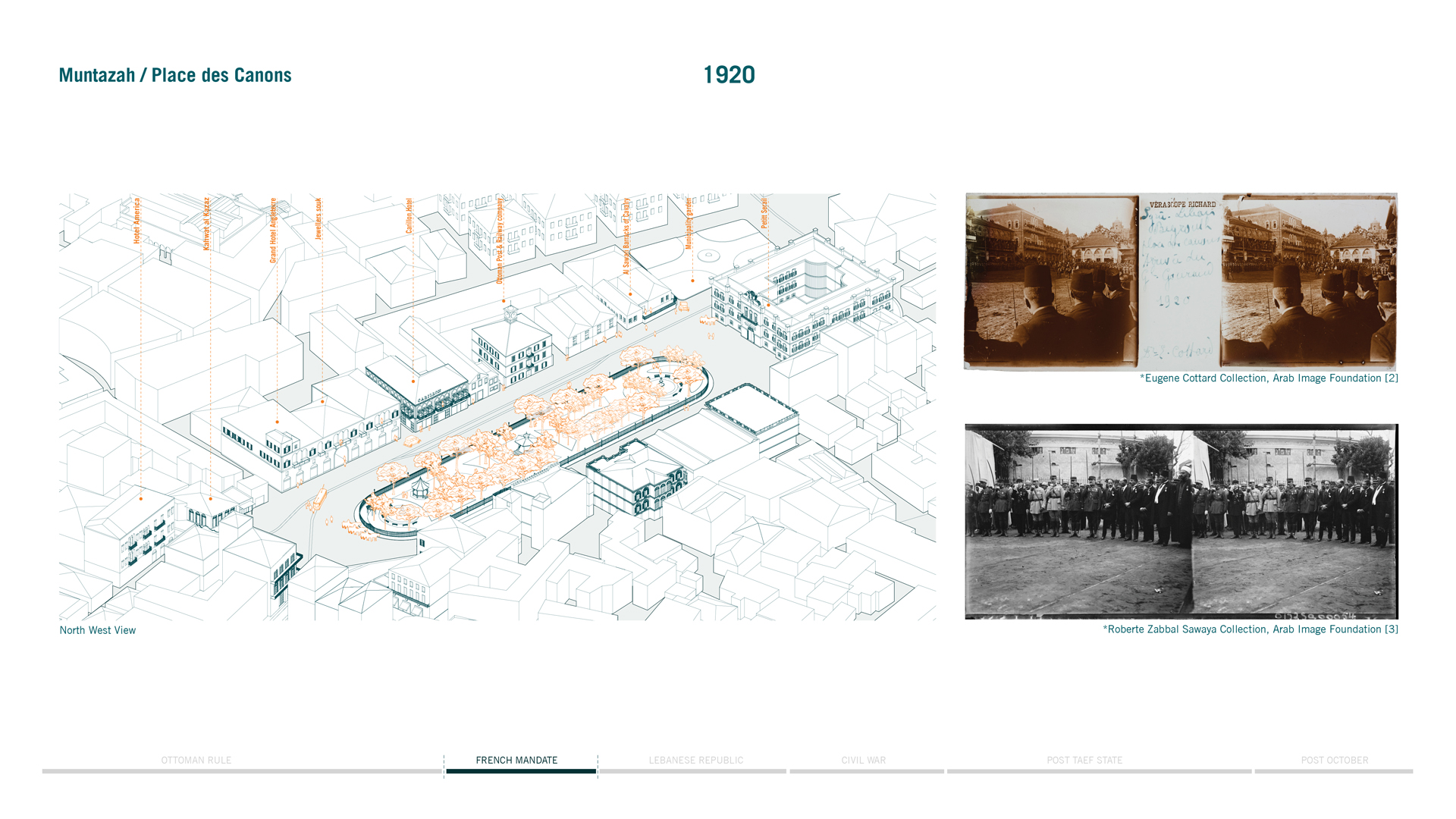

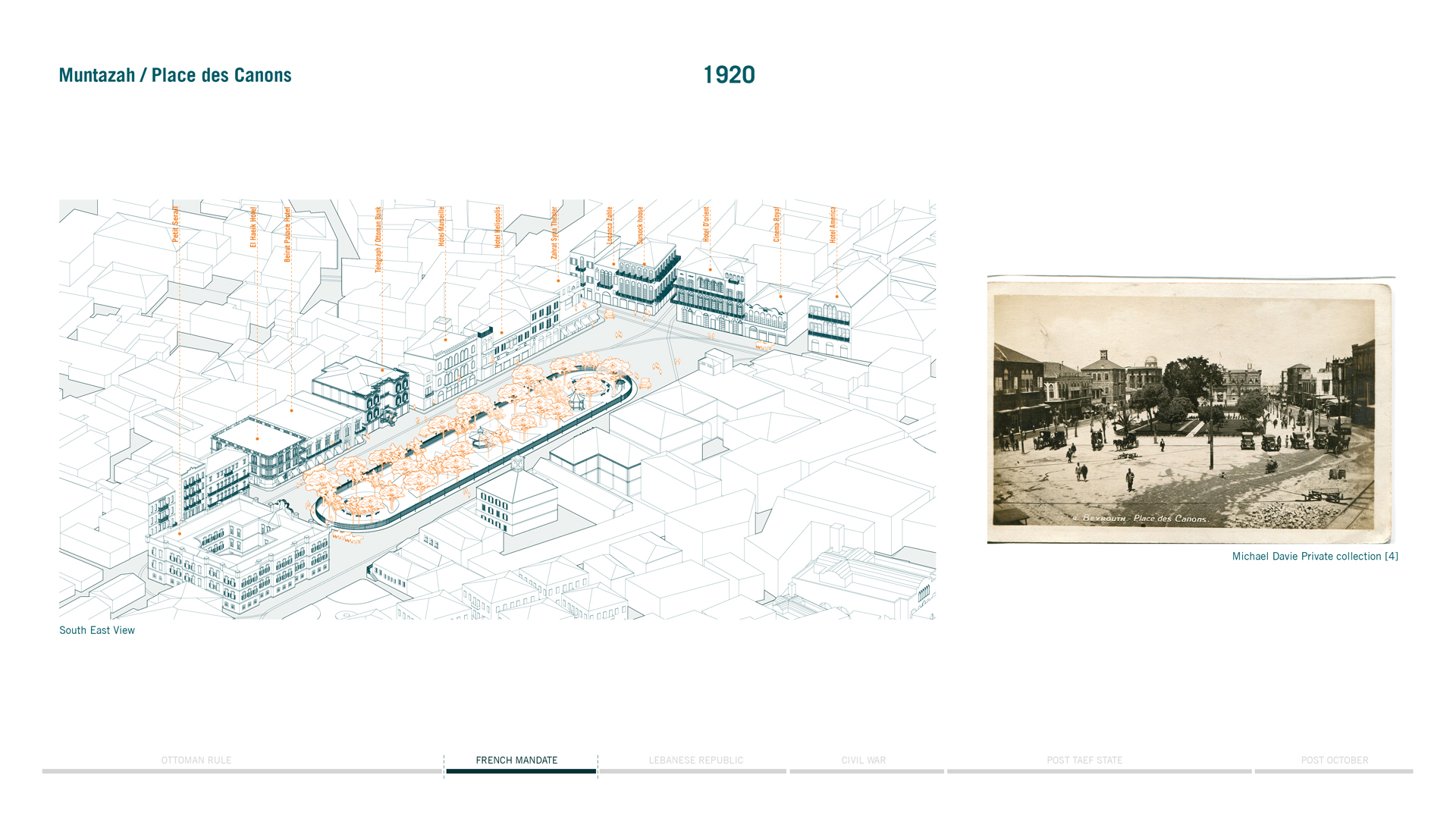

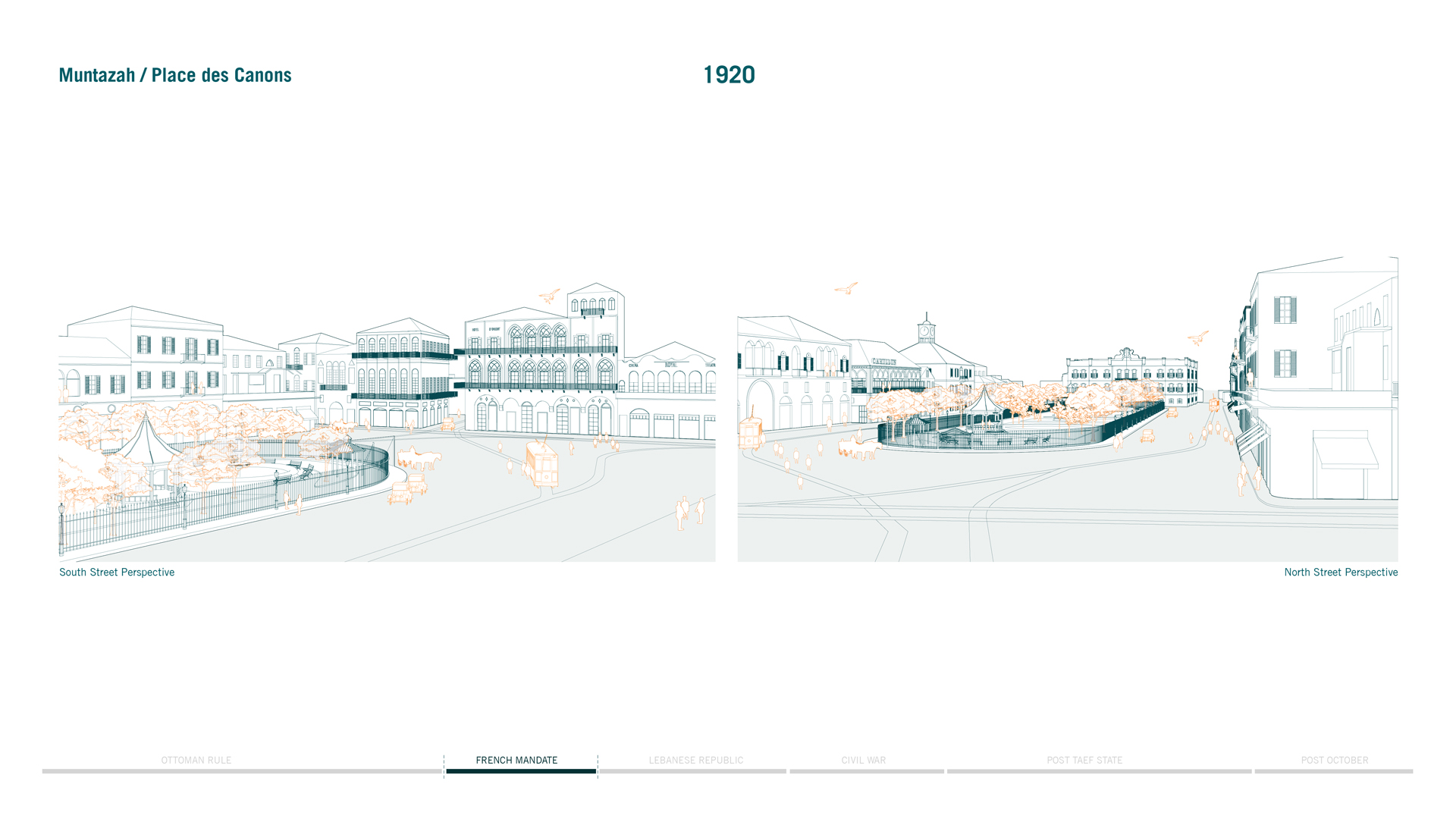

1920 - Muntazah / Place des Canons

The 1920s witnessed radical changes as the French take over remnants of the Ottoman Empire after World War I. The French proclaimed Greater Lebanon, and initiated their mandate with ambitious urban renewal projects, affecting the old city and reshaping its historic quarters.

The Beirut International Fair was hosted in the city with Pavilions installed inside the garden. Furthering this transformation, the square was redesigned as a modern French garden and fountain, and its centrality rose as hotels, cafes, and theaters prospered. The square also witnessed political demonstrations amid demands for local governance.

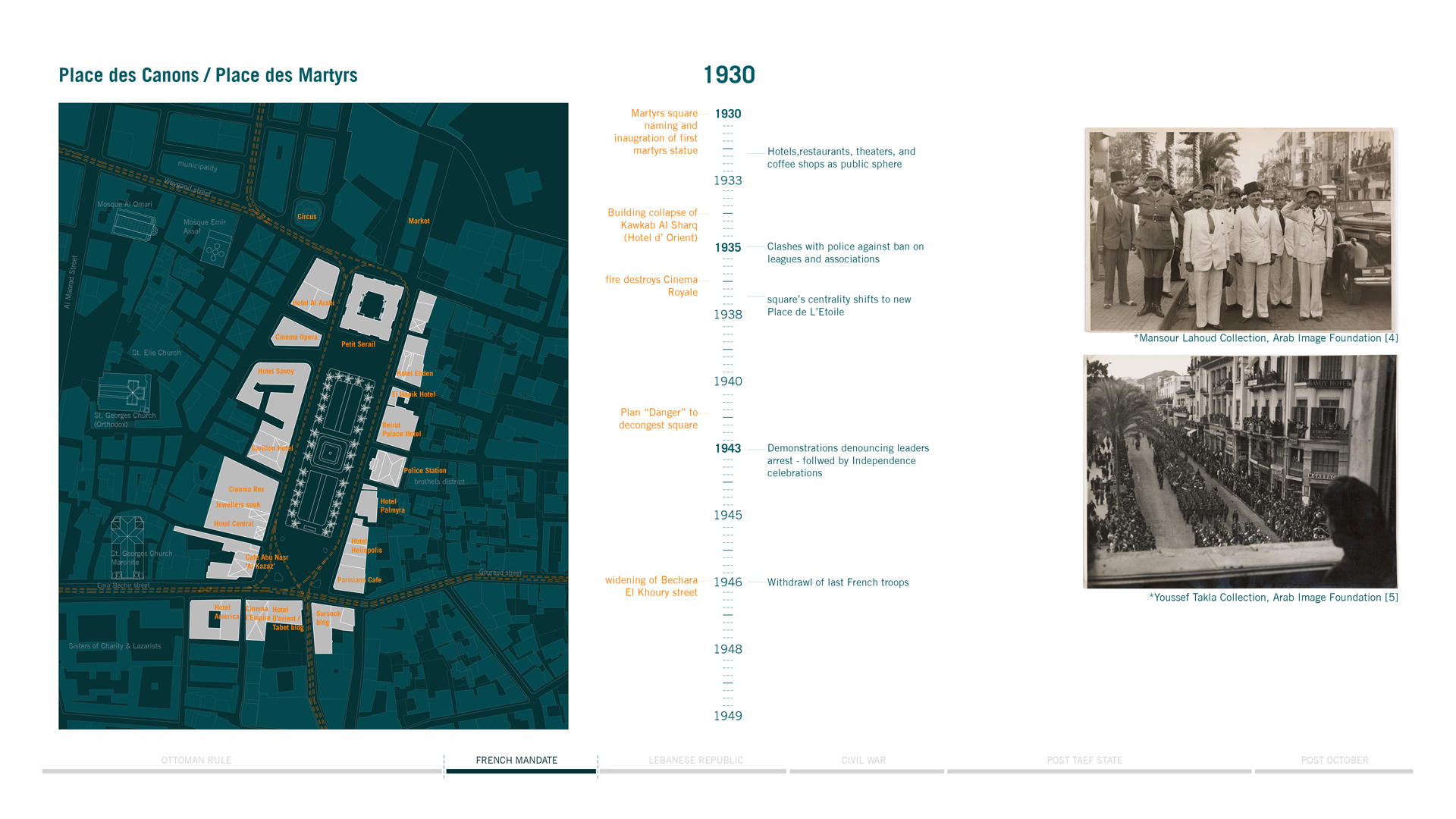

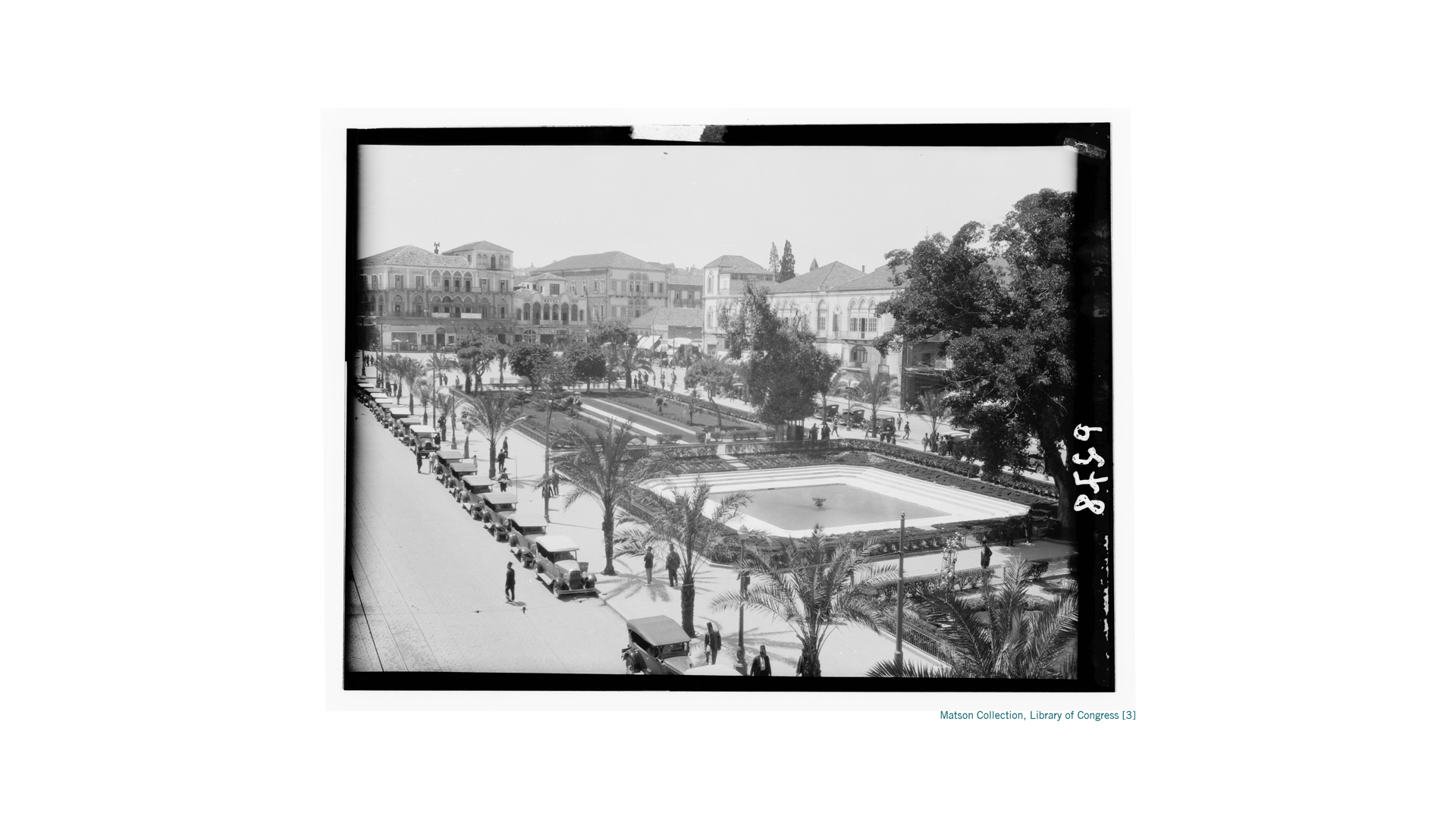

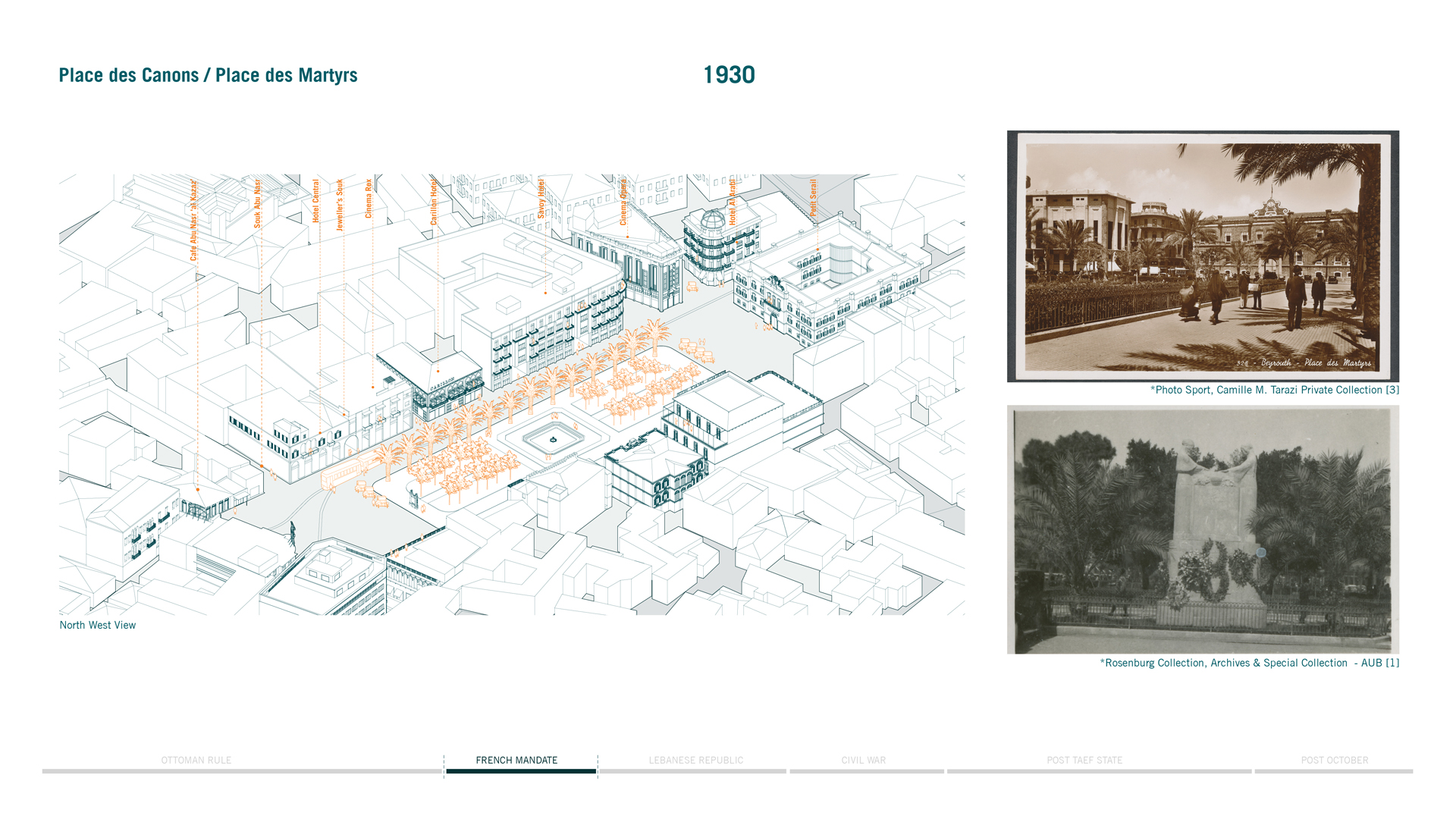

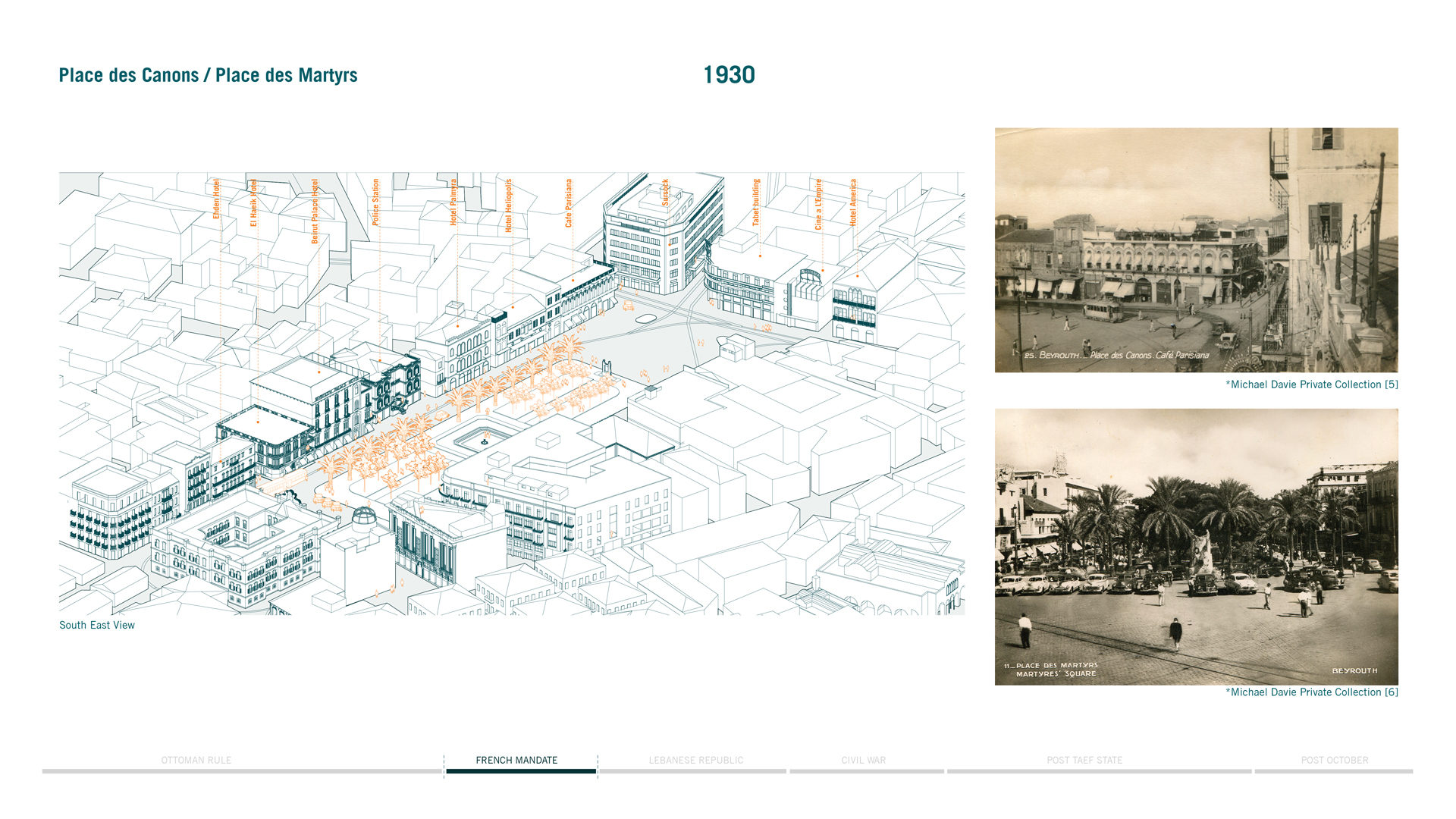

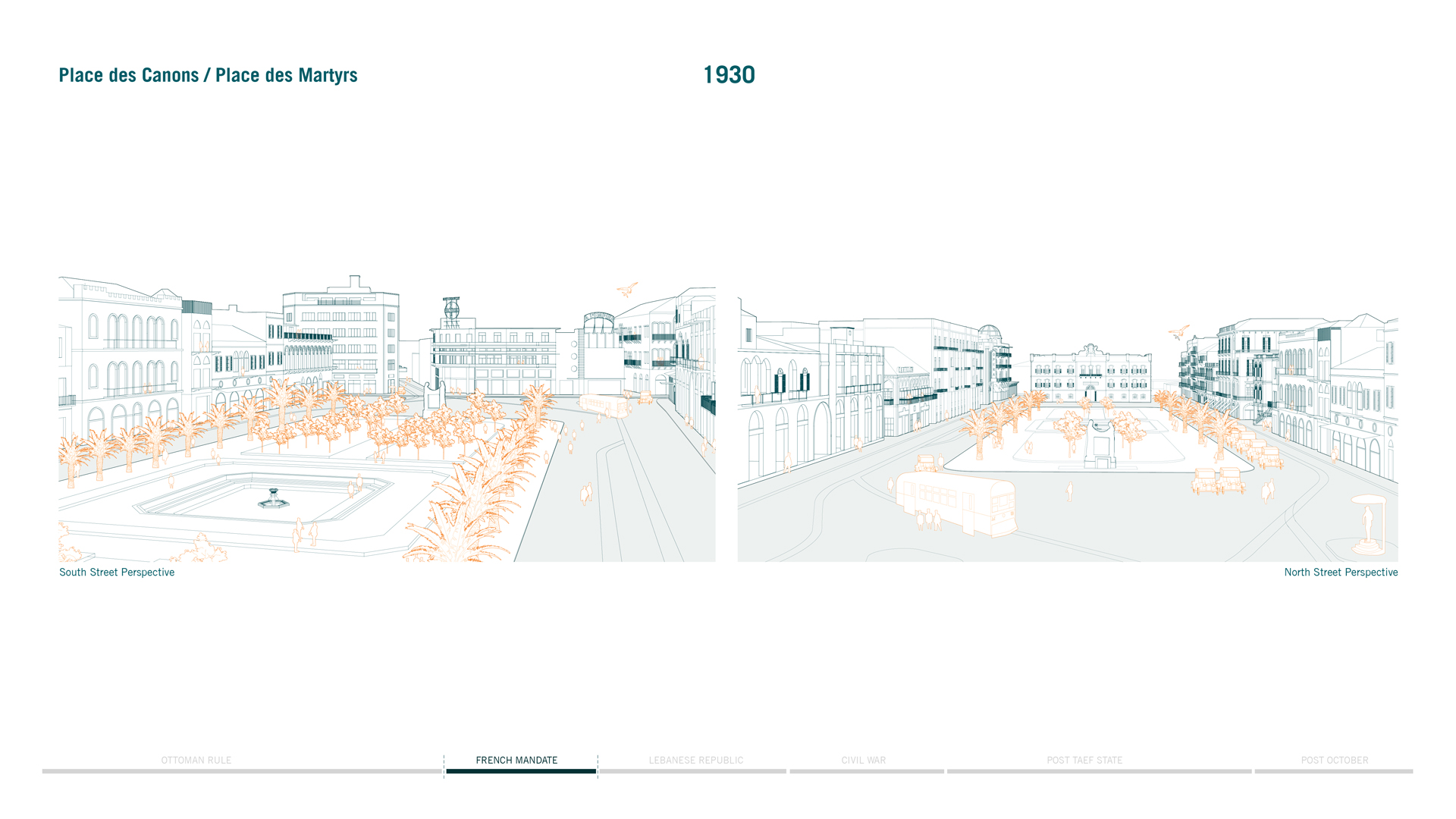

1930 - Place des Canons / Place des Martyrs

The redesigned square was renamed Martyrs square with the installation of the Weeping Women statue, commemorating the Martyrs of 1916. The collision between the local government and the mandate escalated in 1943, and the square witnessed mass demonstrations supporting local leaders, arrested for defiance.

Following the local leaders’ release and the declaration of Lebanon’s Independence, the square amassed huge celebrations and signaled a new future. Its role however as a commercial and political center, gradually shifted towards the recently completed Place de l’Etoile.

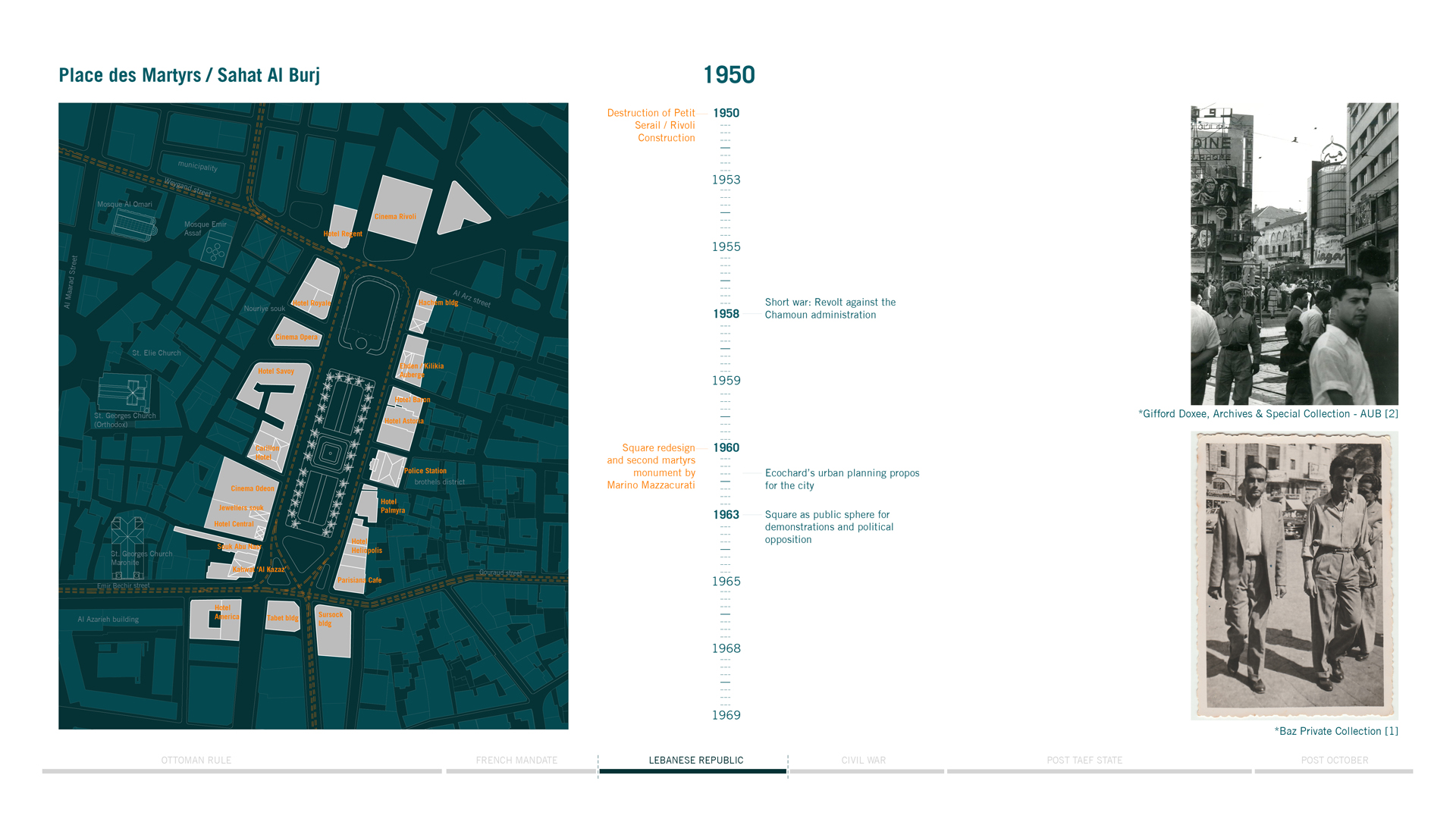

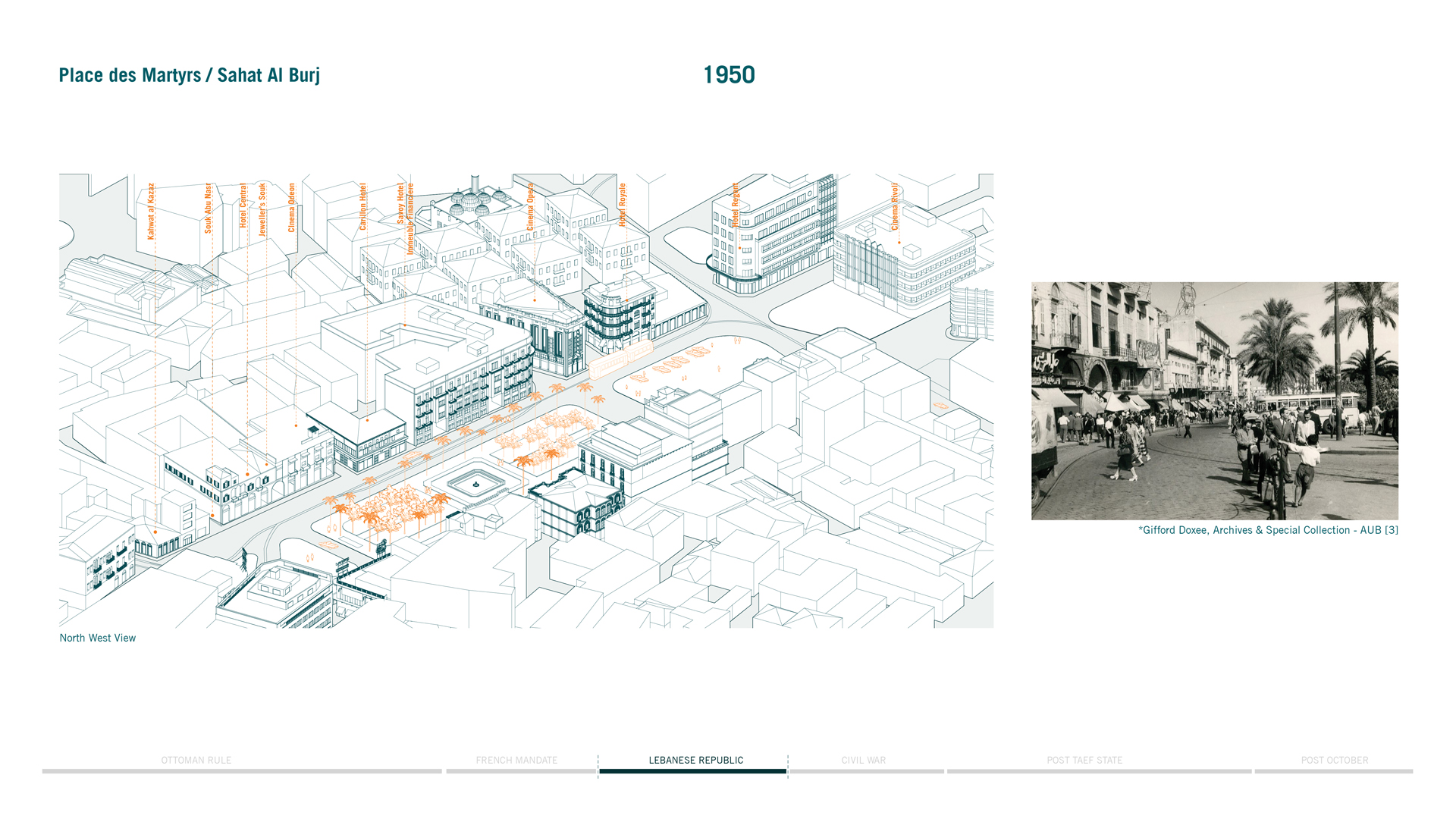

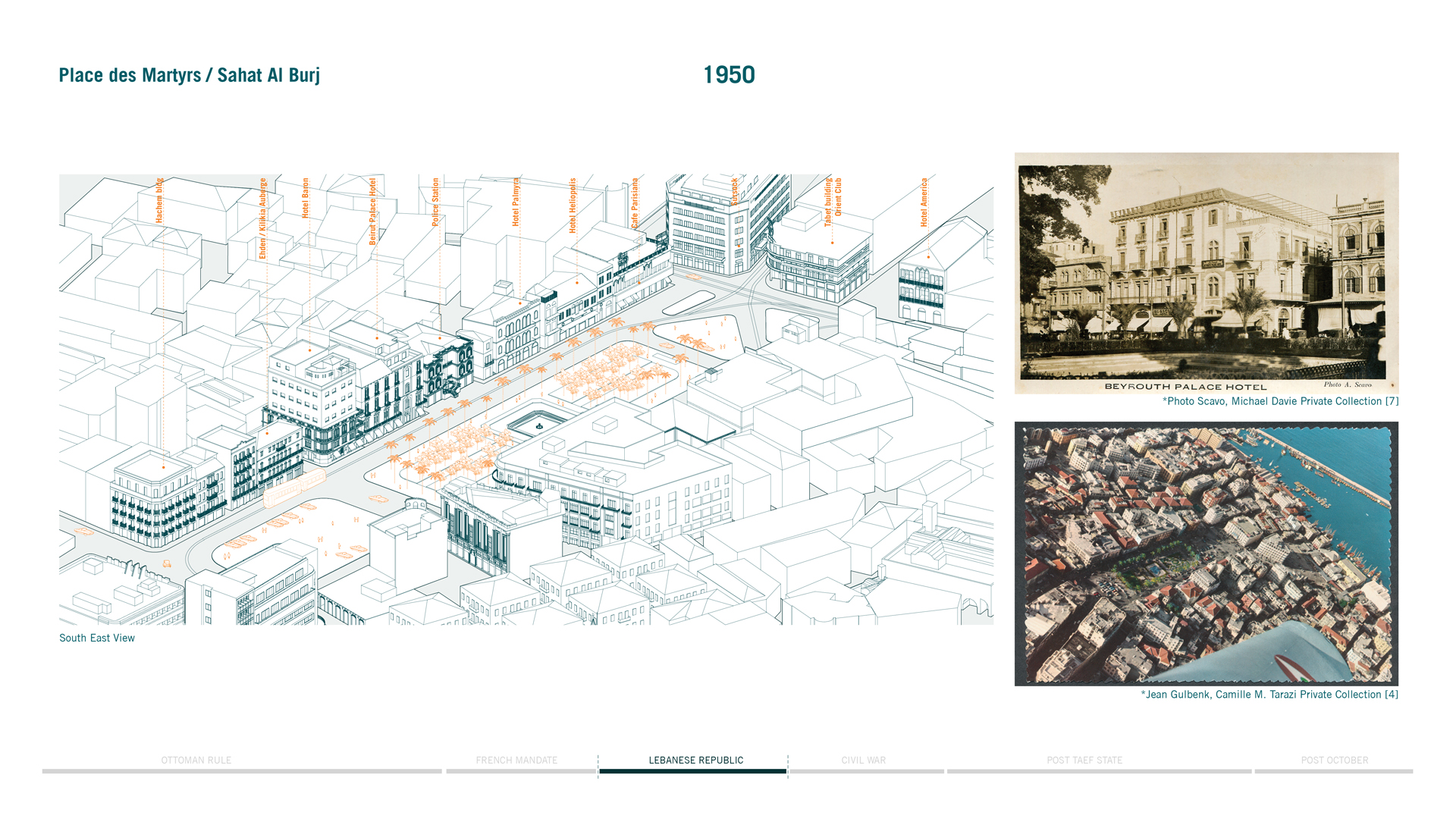

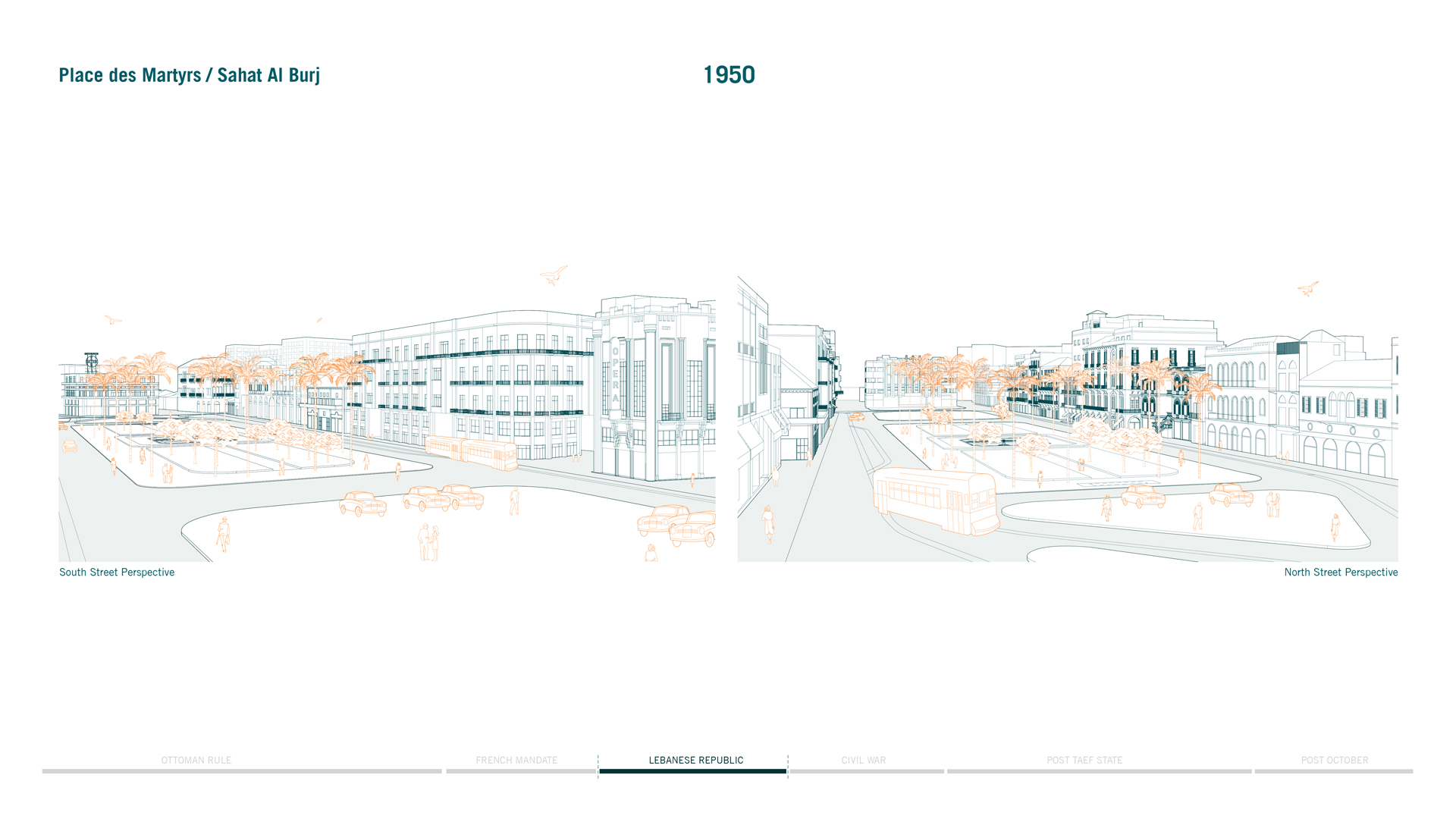

1950 - Place des Martyrs / Sahat Al Burj

The 50s established the square as a leisure and cultural center, with the proliferation of theaters, cinemas, and hotels. After the controversy surrounding it, the Weeping Women statue was removed, as plans to redesign the square in the Chehab administration period were underway.

Ambitious urban plan by Michel Ecochard proposed the opening of the square to the sea. The Rivoli Cinema instead was built in the 60s bordering its northern edge, and a new martyrs’ monument was installed in its center. A short war in 1958 of local conflict amid regional political shifts, positioned the square as a political node.

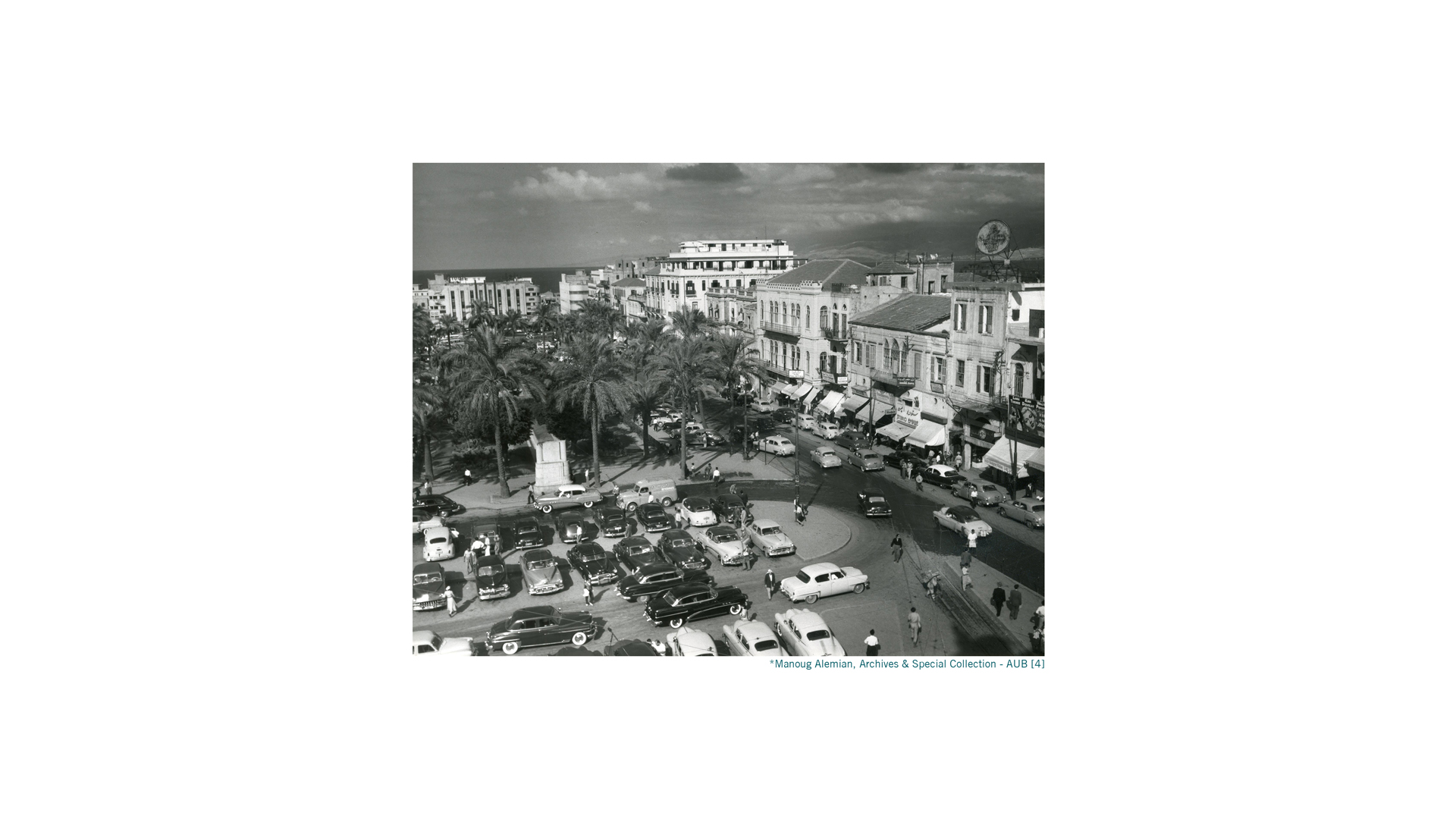

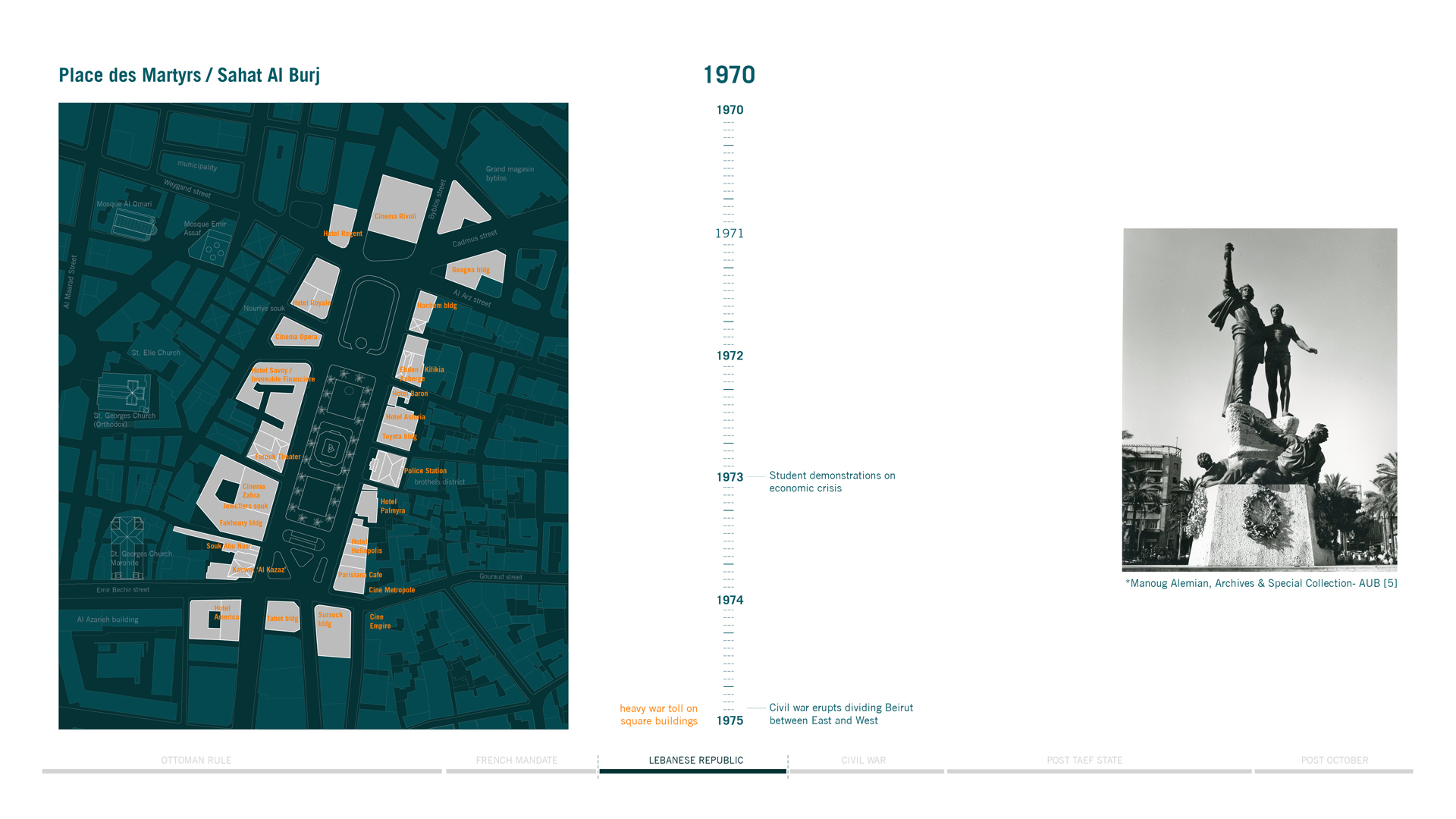

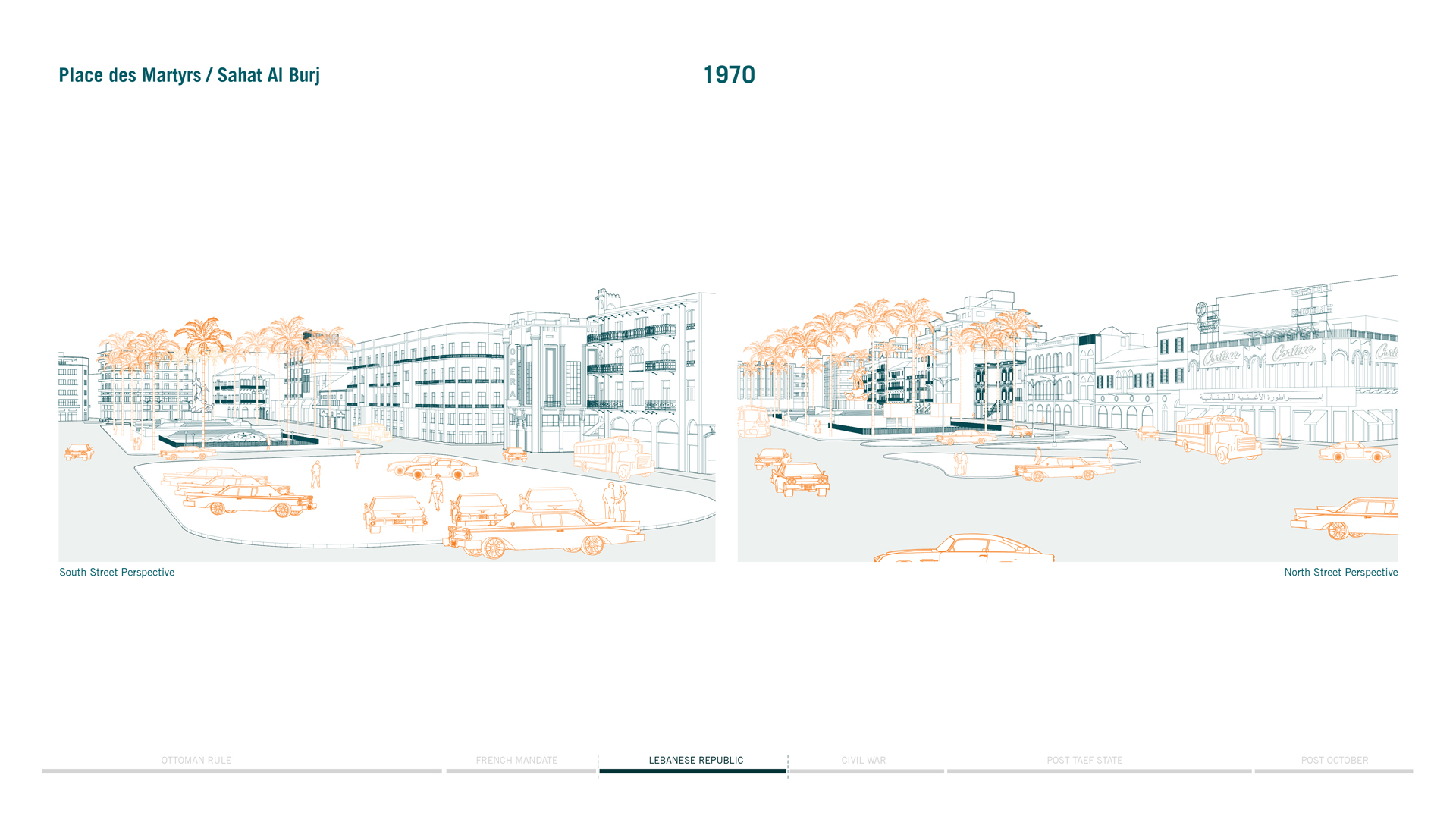

1970- Place des Martyrs / Sahat Al Burj

The square’s role as a transportation and cultural hub manifested strongly in the 70s, with taxis, buses, congested streets, and daily performances, with international and Arab movie screenings and theater groups.

Rising tensions escalated with student demonstrations in the period preceding 1975, when the 15 year-long civil war ignited. The square transformed into a center of conflict along a divisive line between East and West Beirut. Heavy with checkpoints and snipers, the square, once a uniting center, became a junction of fear and division.

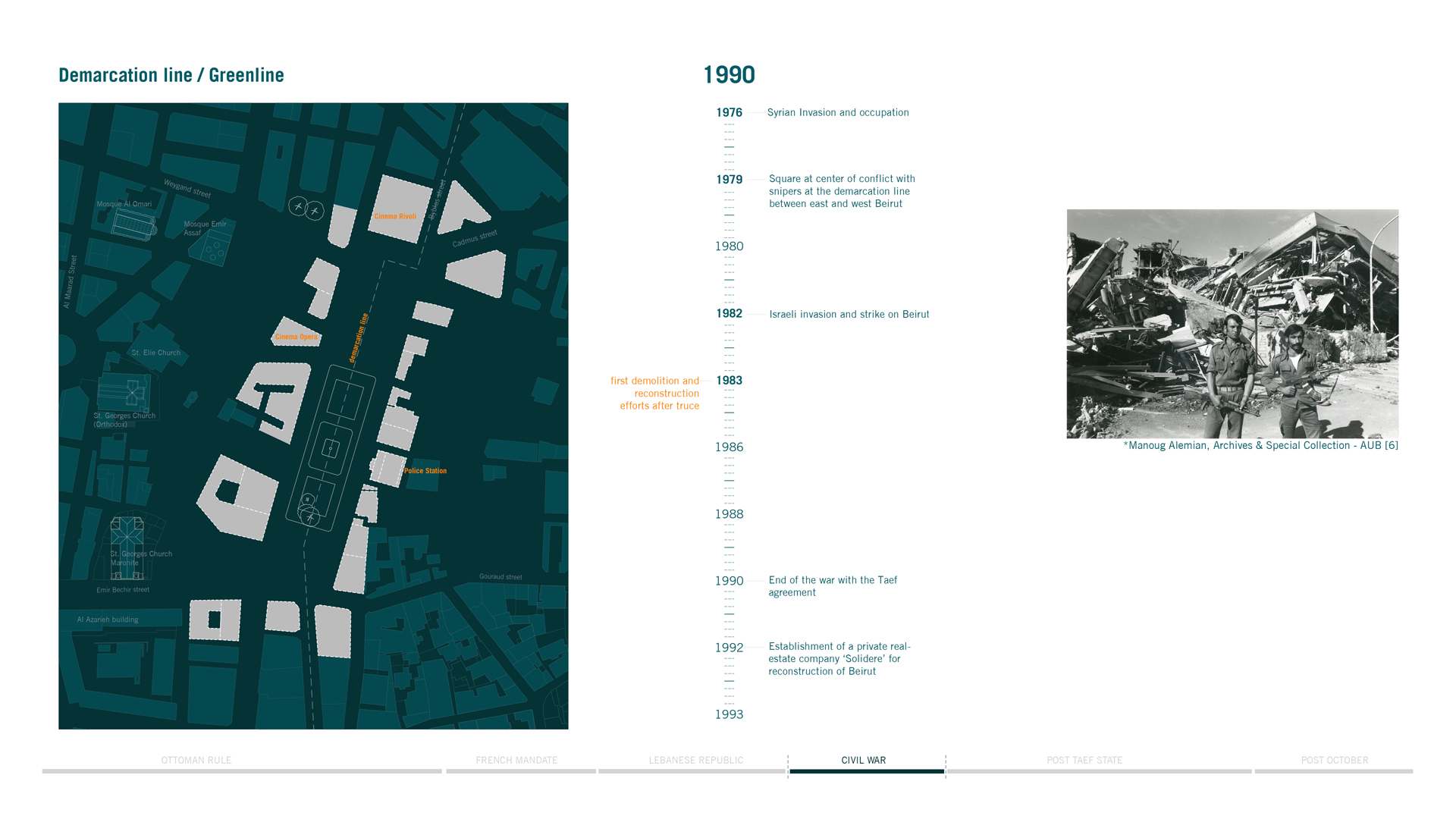

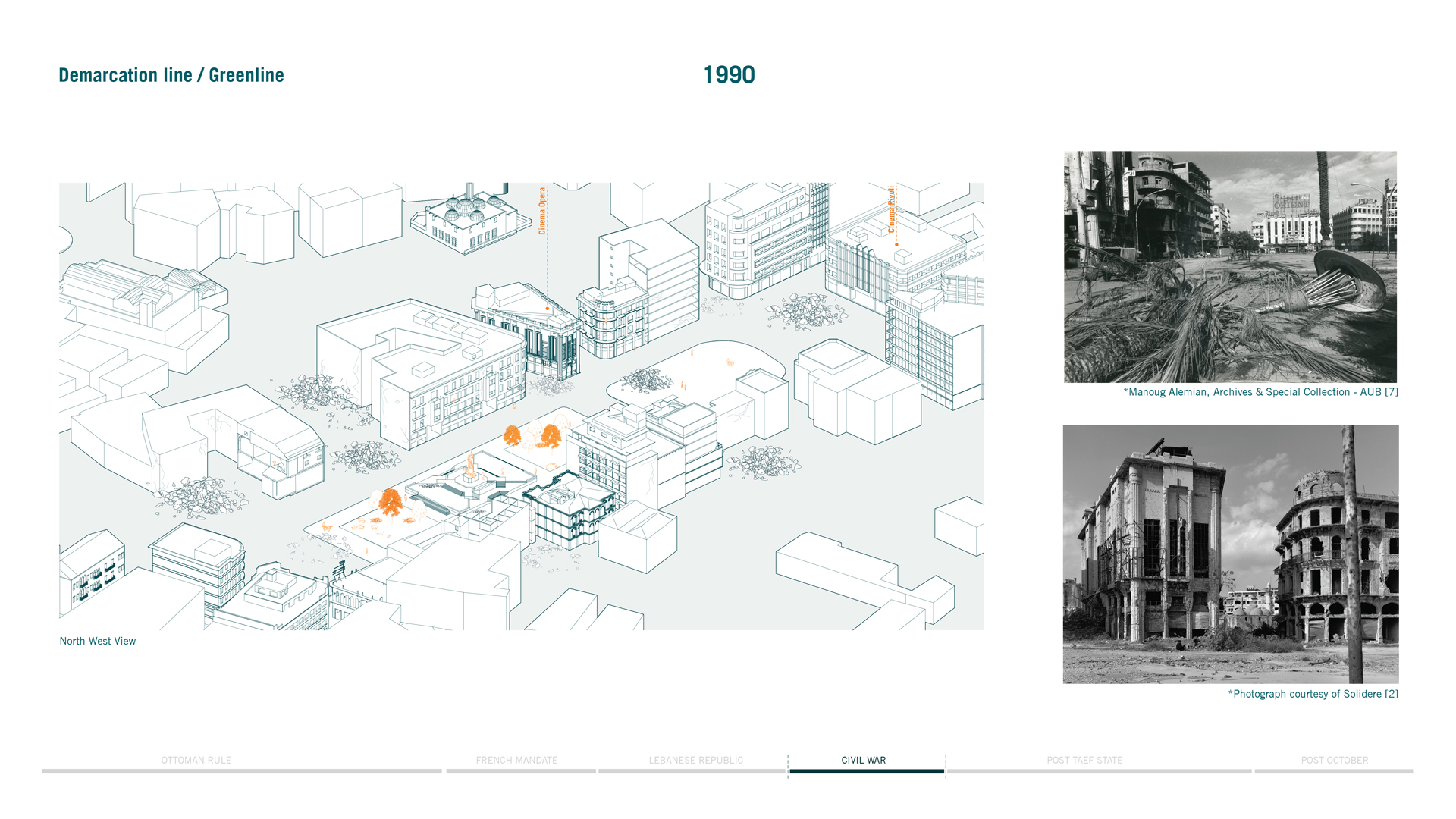

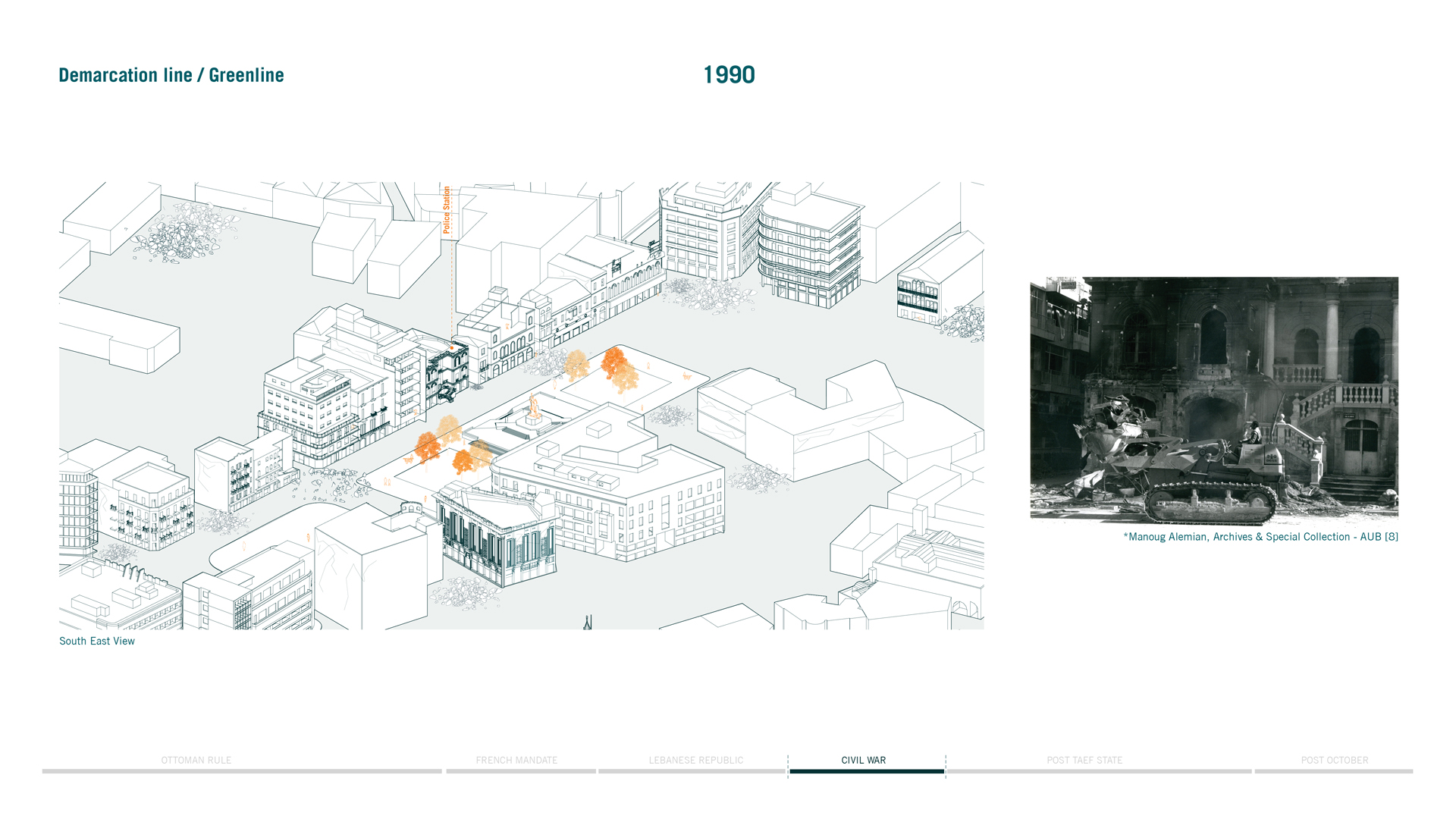

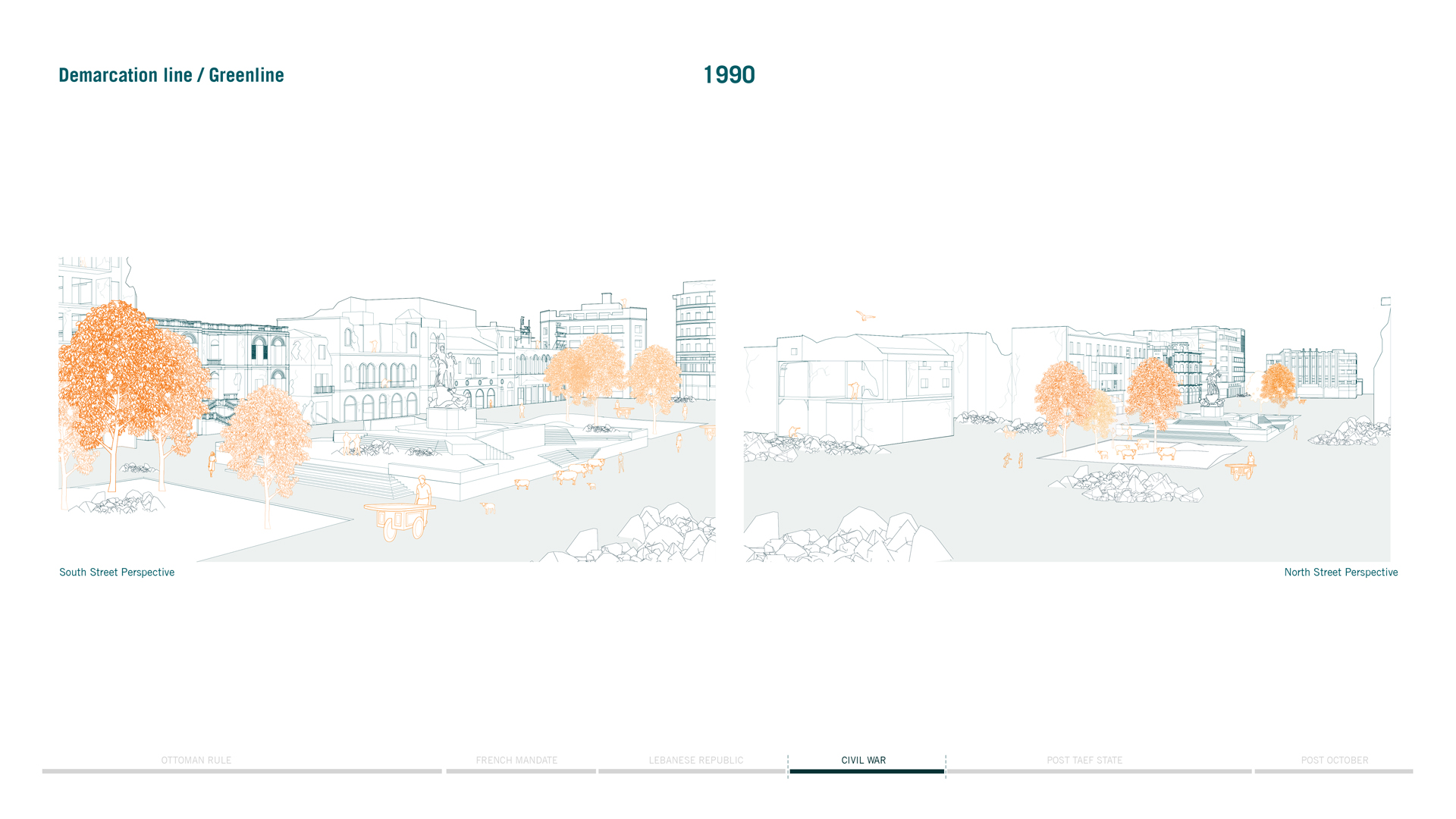

1990- Demarcation line / Greenline

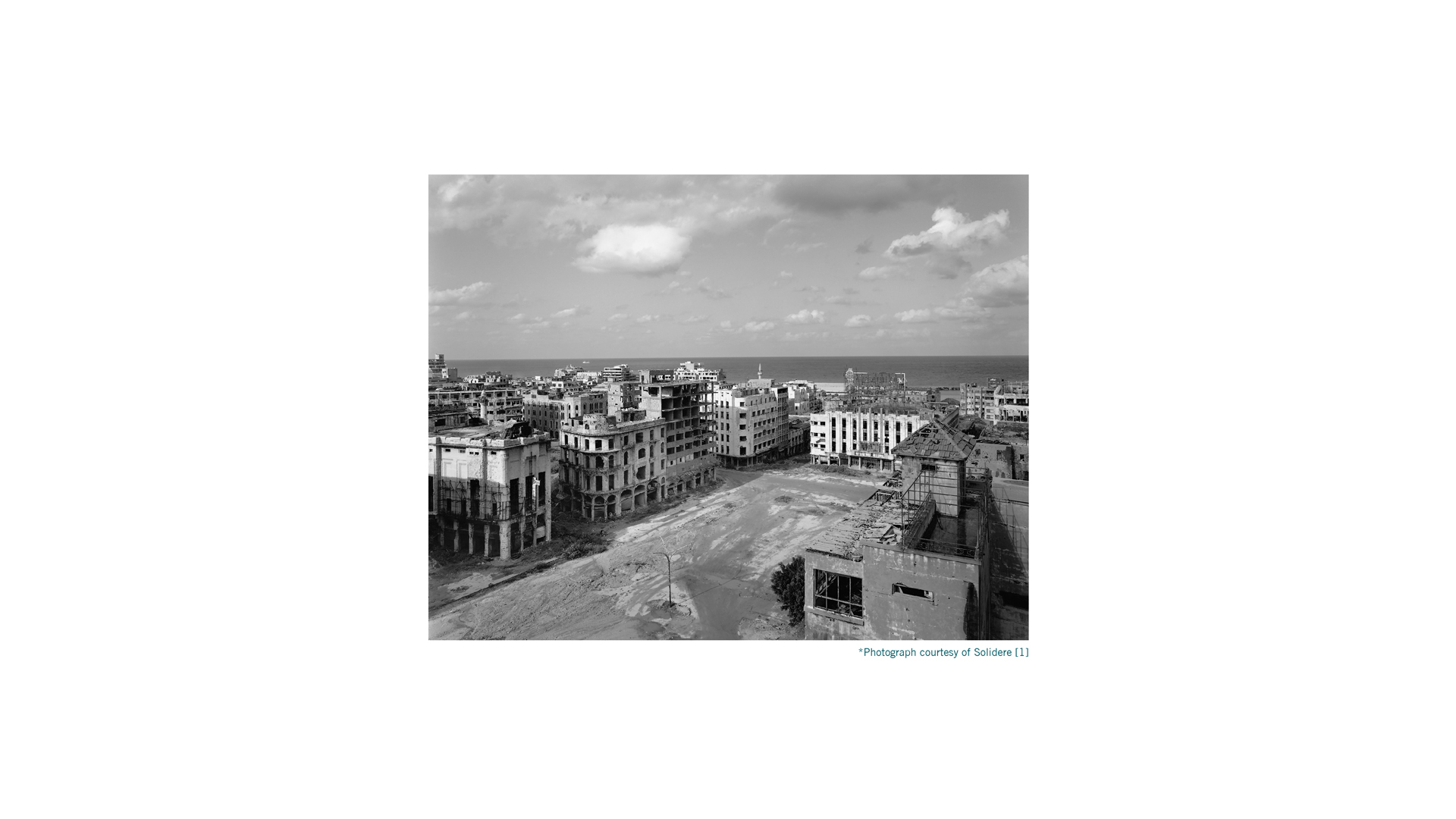

The 15-year war distorted the square, turning it into a demarcation zone and wild no-man’s land. Its buildings and surrounding urban fabric were heavily destroyed, with bullet ridden facades as its central monument remained standing.

After the end of the war, the square sat in limbo, with the occasional visitors, journalists, and local vendors selling souvenirs of its lost history.

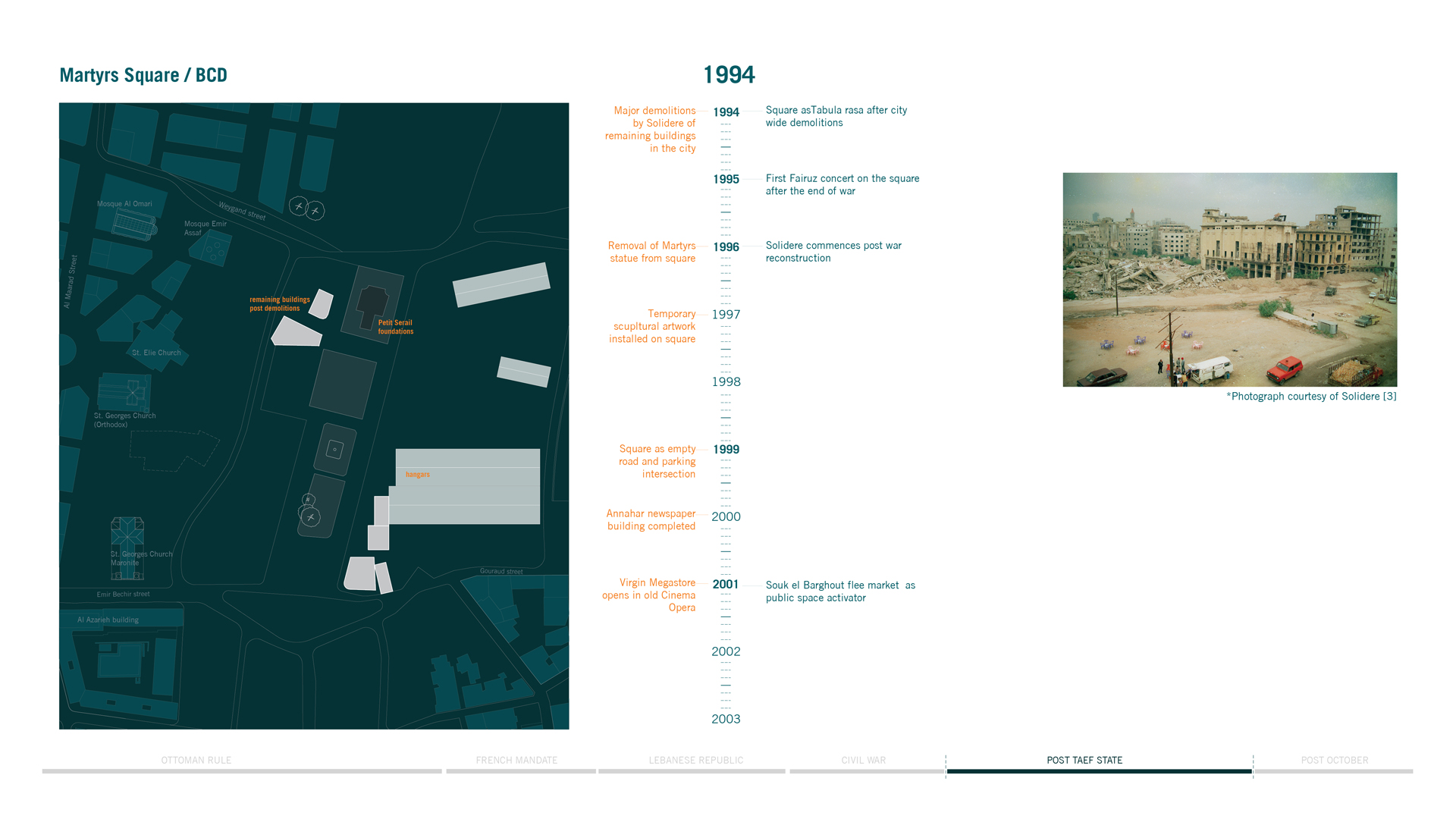

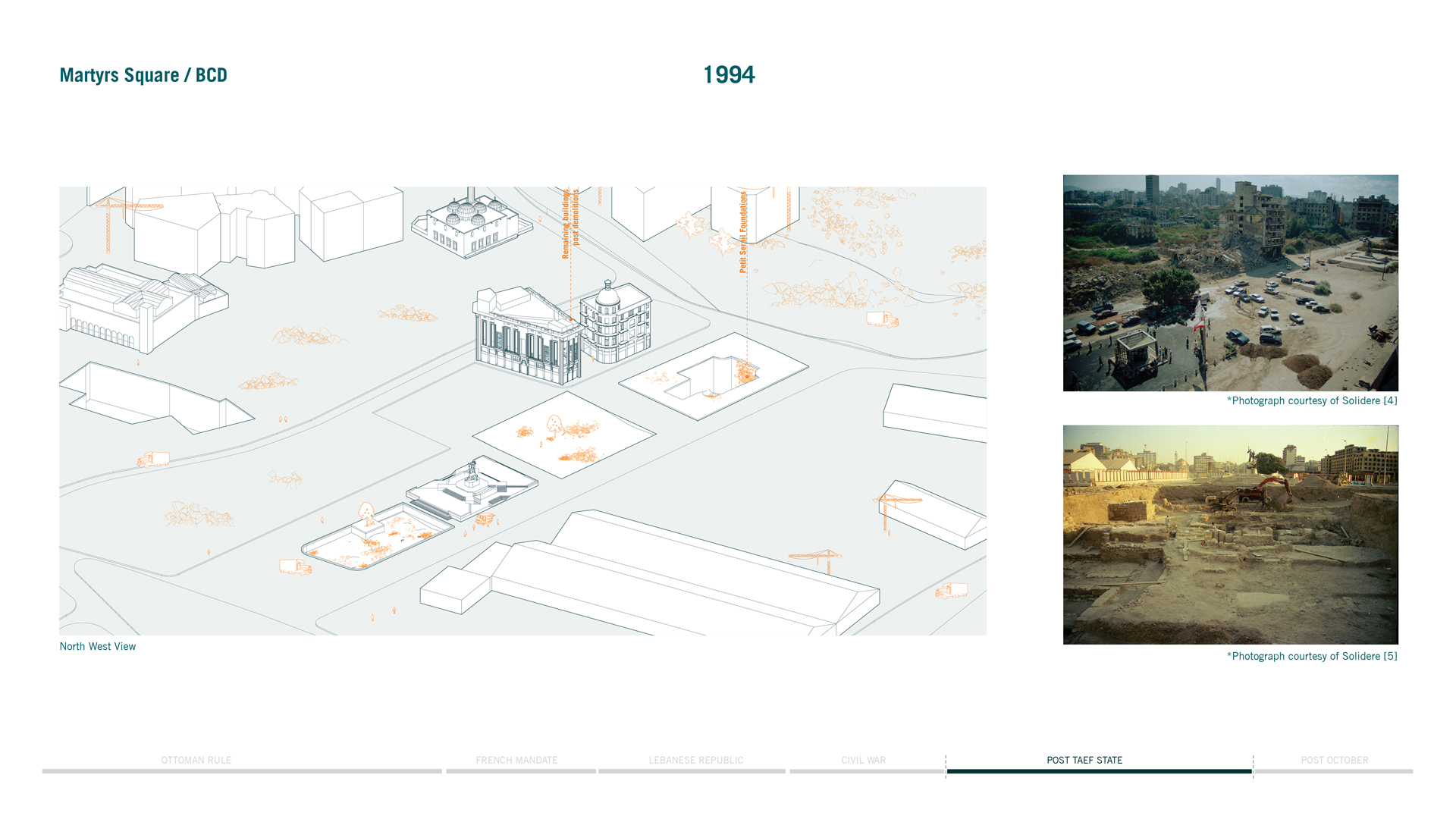

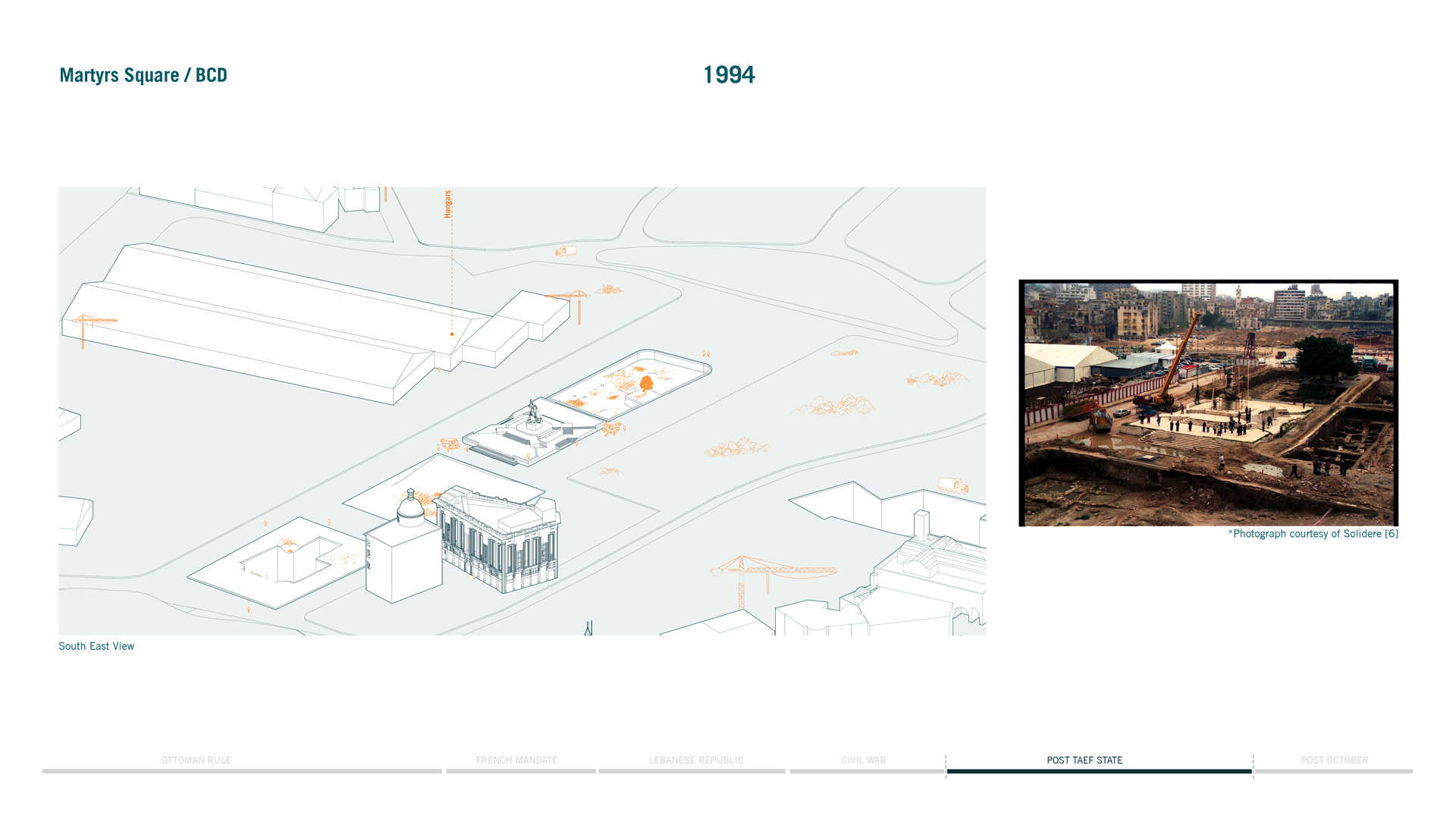

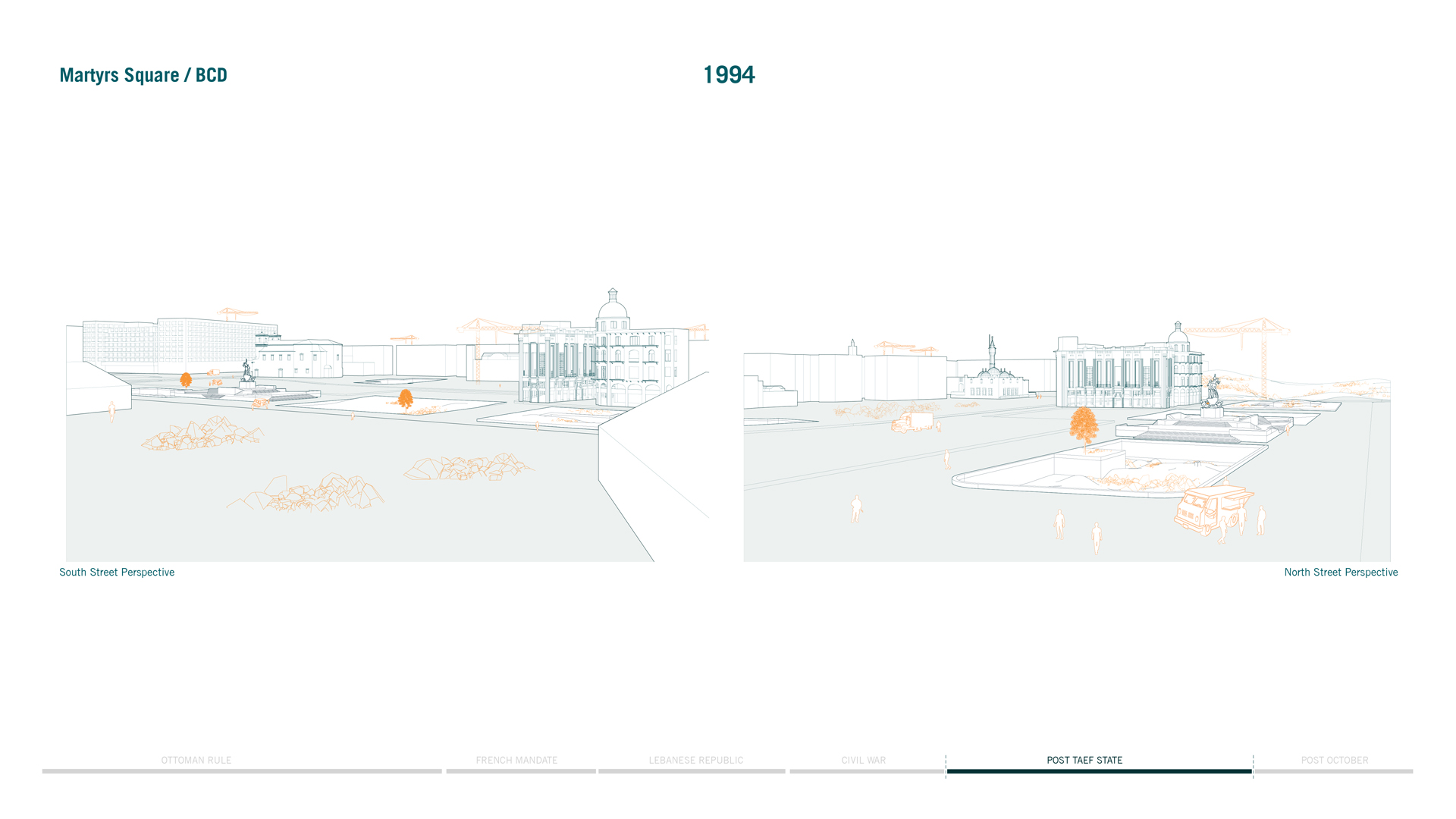

1994- Martyrs Square / BCD

After the establishment of Solidere, a private company for reconstructing Beirut, the square witnessed major demolitions, with only two buildings surviving its mass transformation. The area shifted into a reconstruction ground with hangars, trucks, and piles of rubble, while the Martyrs monument was relocated for restoration.

After its clearing, a first concert by Fairuz on the square signaled a new era, pushing the war into a distant memory, enforcing a long collective social amnesia. Popular market events and artwork around the square attempted to bring people back to their lost center, now mostly functioning as a void road junction.

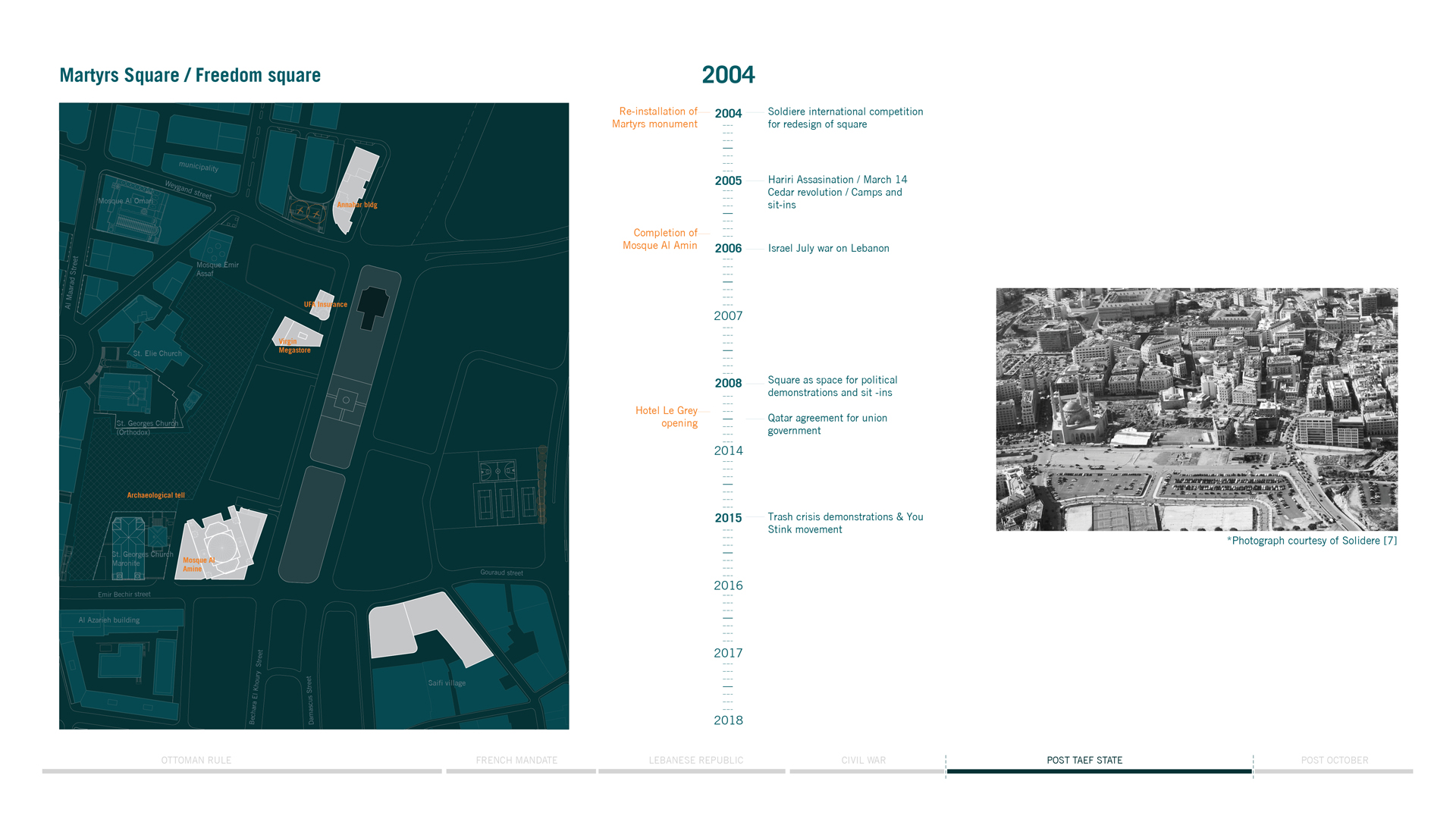

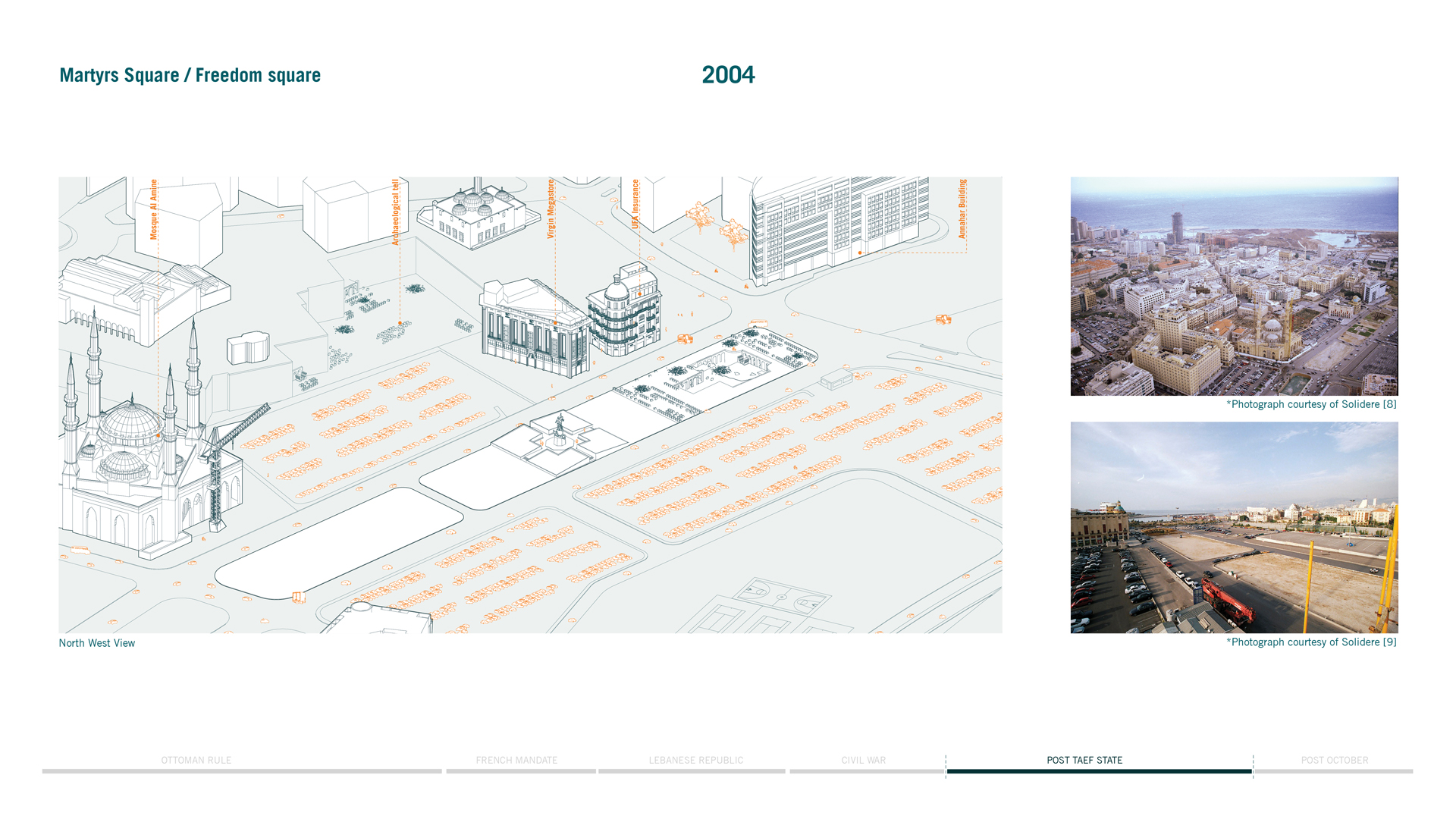

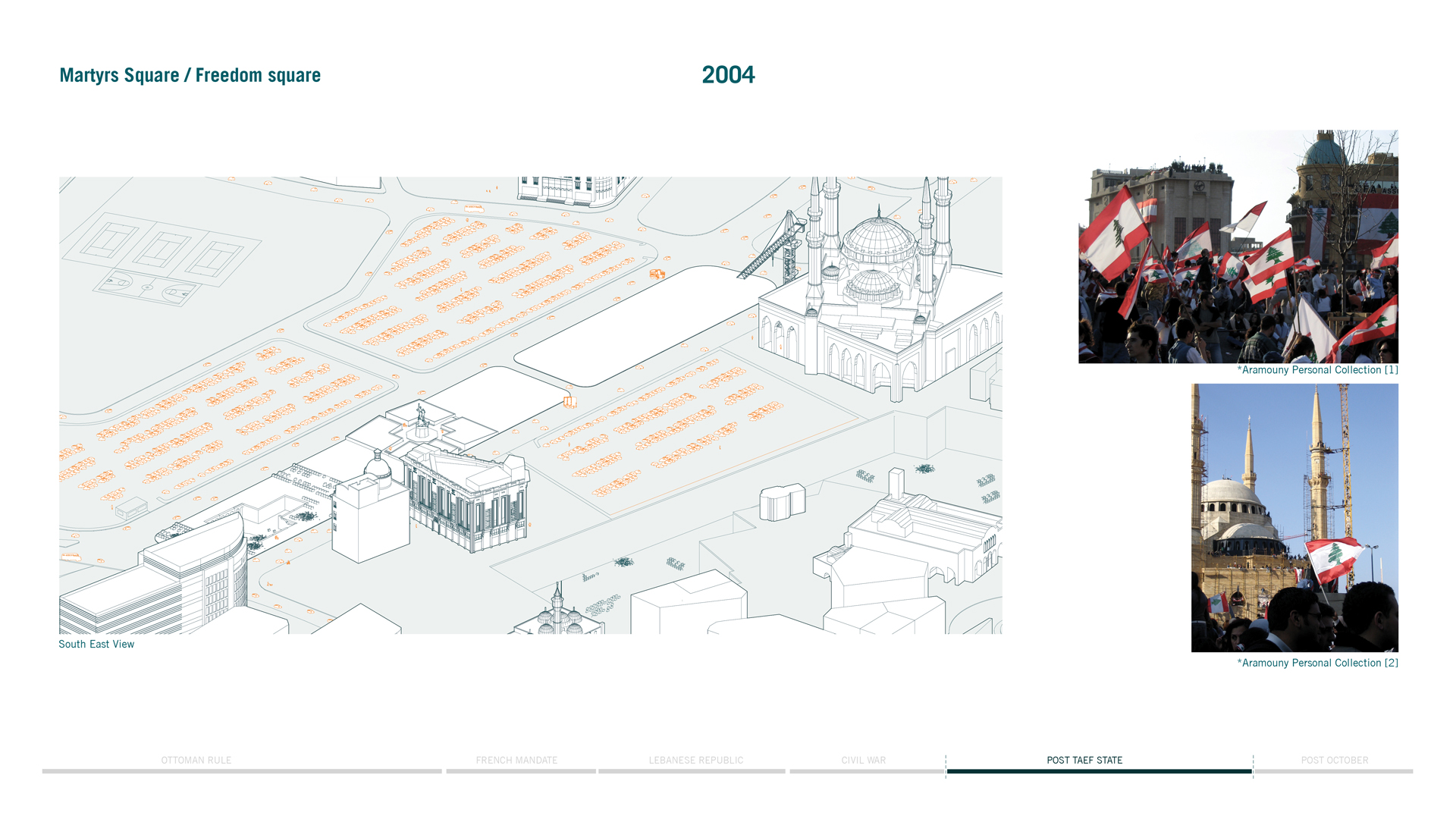

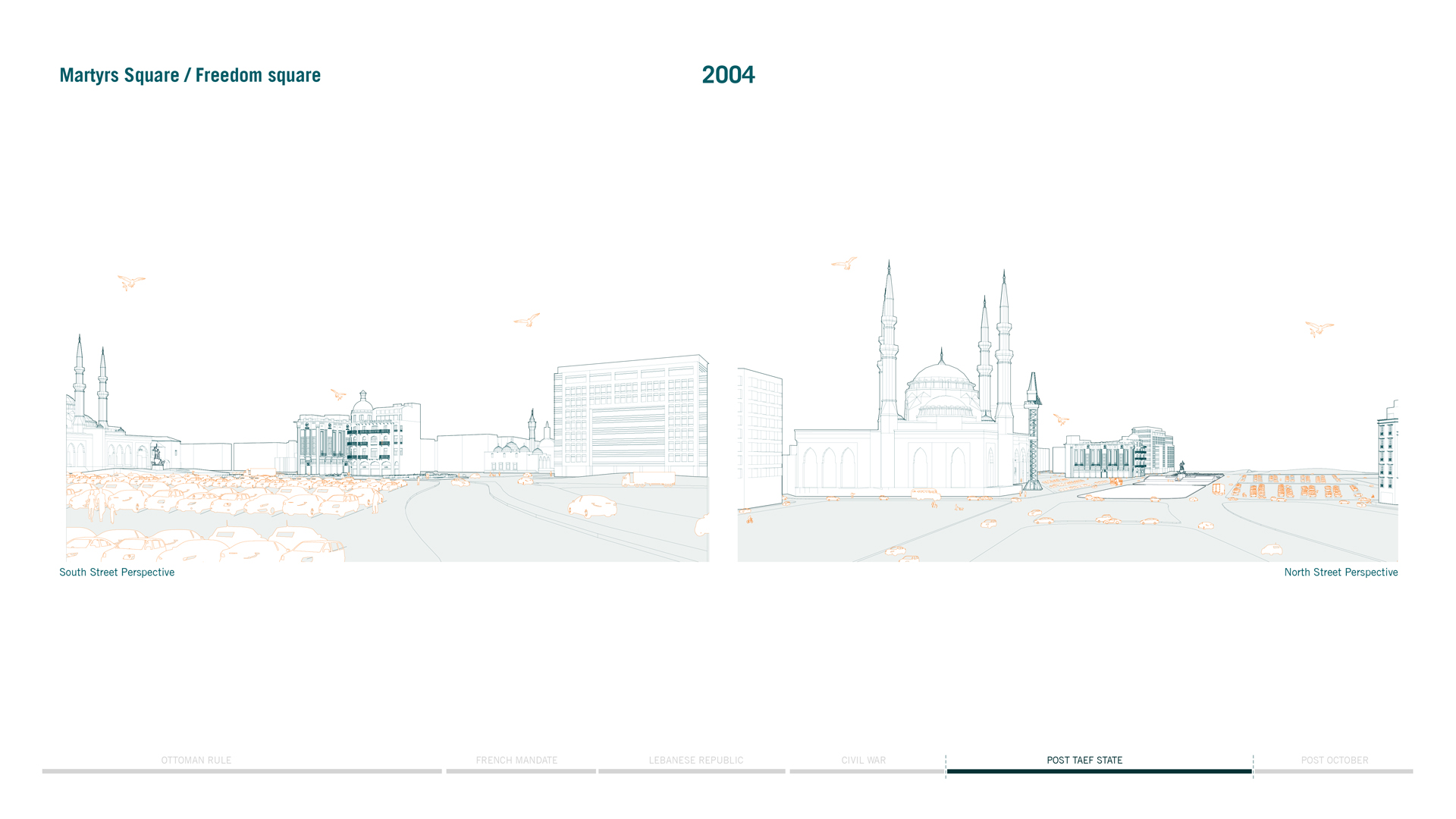

2004 - Martys Square / Freedom Square

The Martyrs monument was reinstalled in 2004 as Solidere launched an international competition for the redesign of the square aligning with their open sea-axis plan. The 2005 assassination of prime minister Rafic Hariri drew millions of people to the square, manifesting against Syria’s role and occupation. This 2005 Cedar revolution gave the square back its role as a political and collective symbol of resistance, labeling it Freedom Square. Different camps and political groups took the square as a space of sit-ins and demonstration, escalating in 2015 with the trash crisis. Despite the tensions, New Year’s Eve celebrations were hosted for several years on the square.

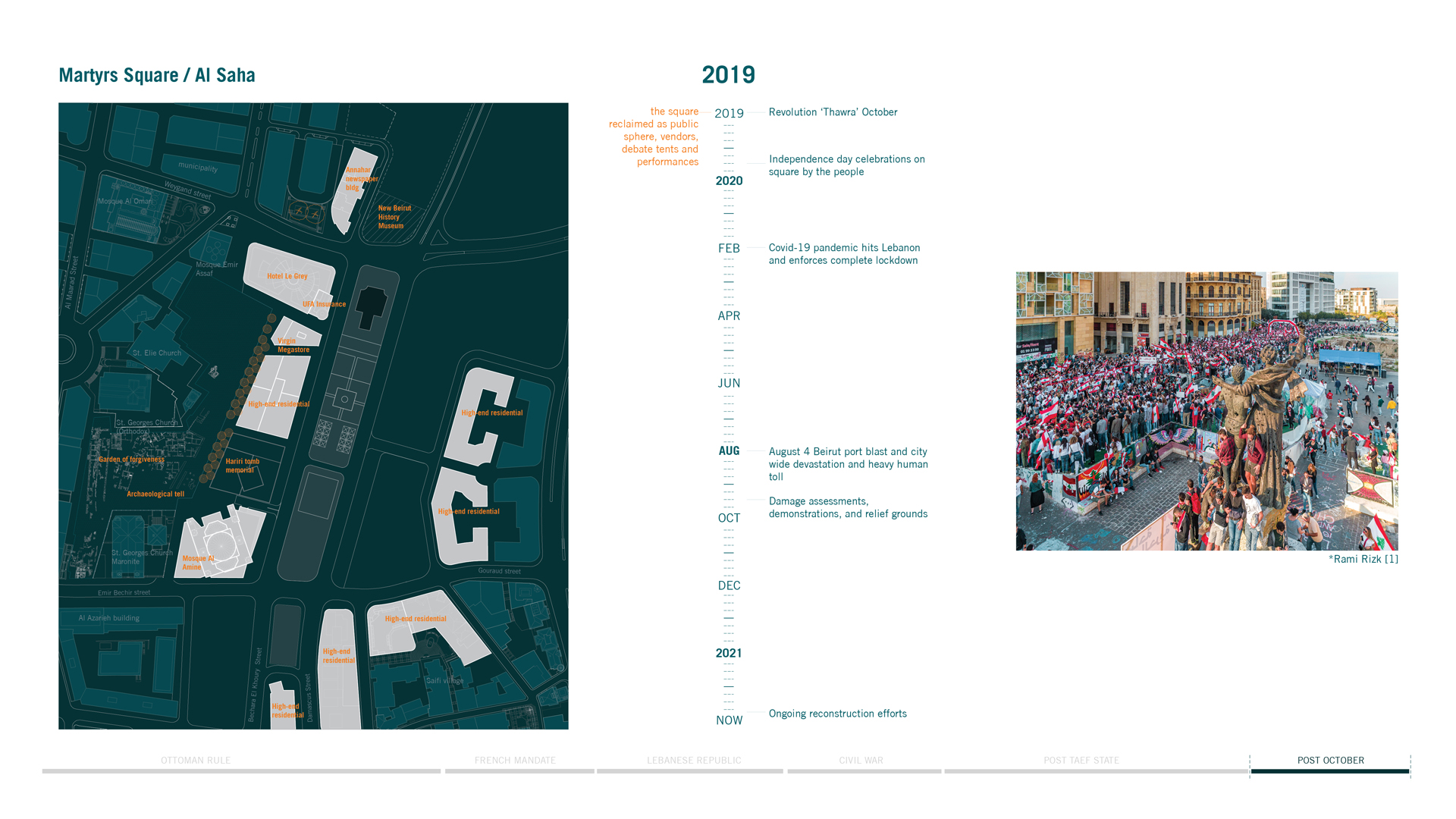

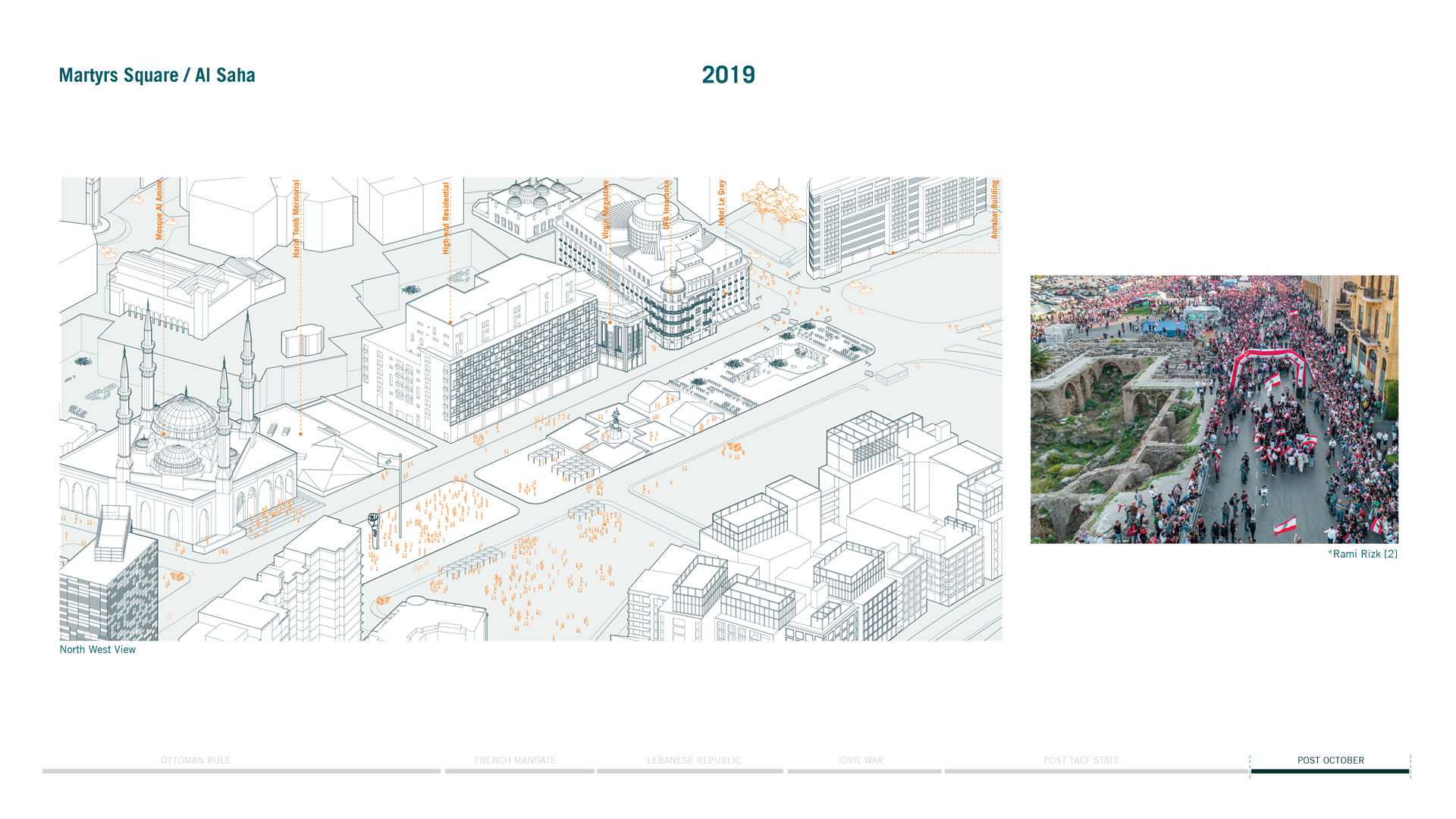

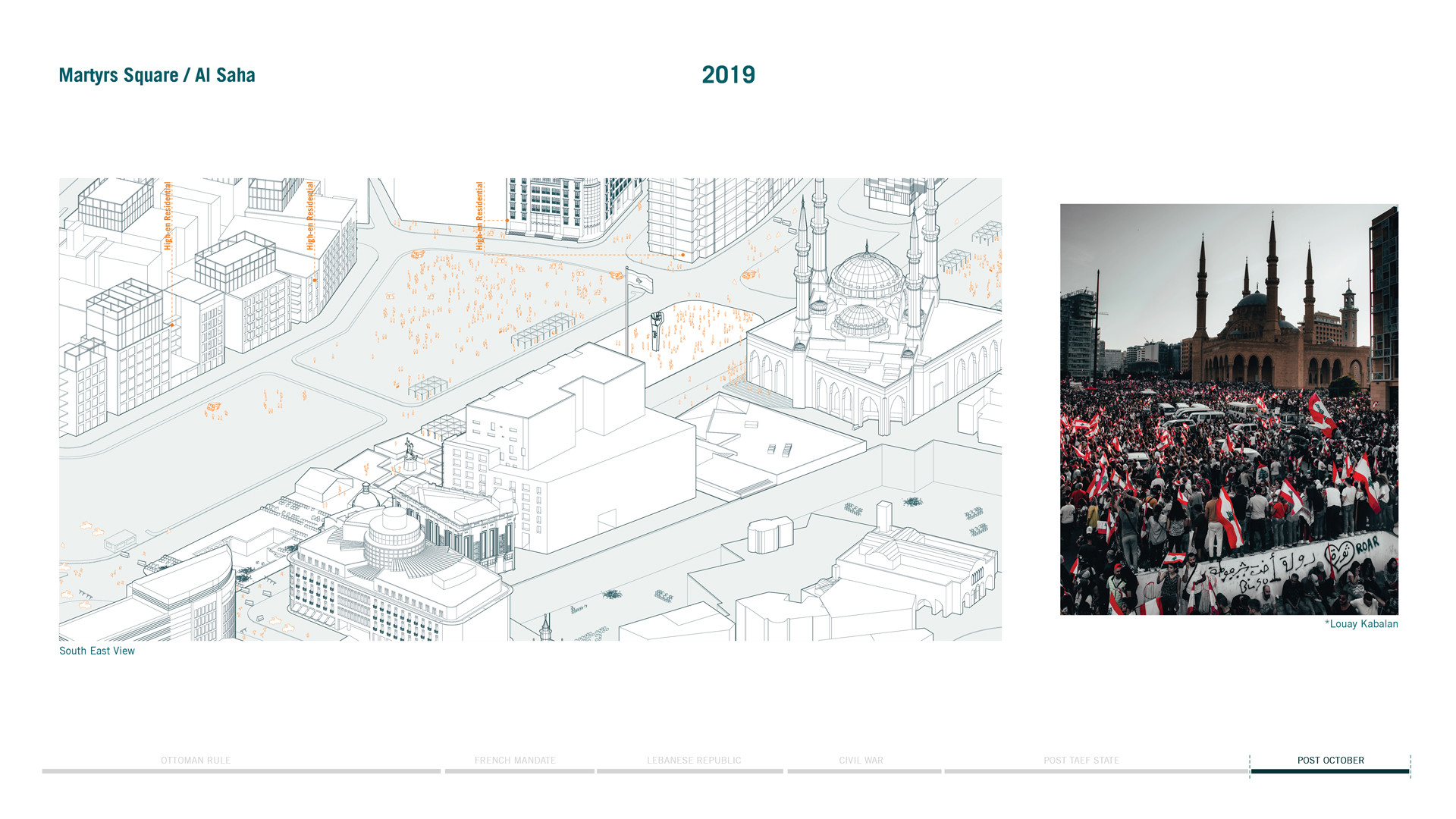

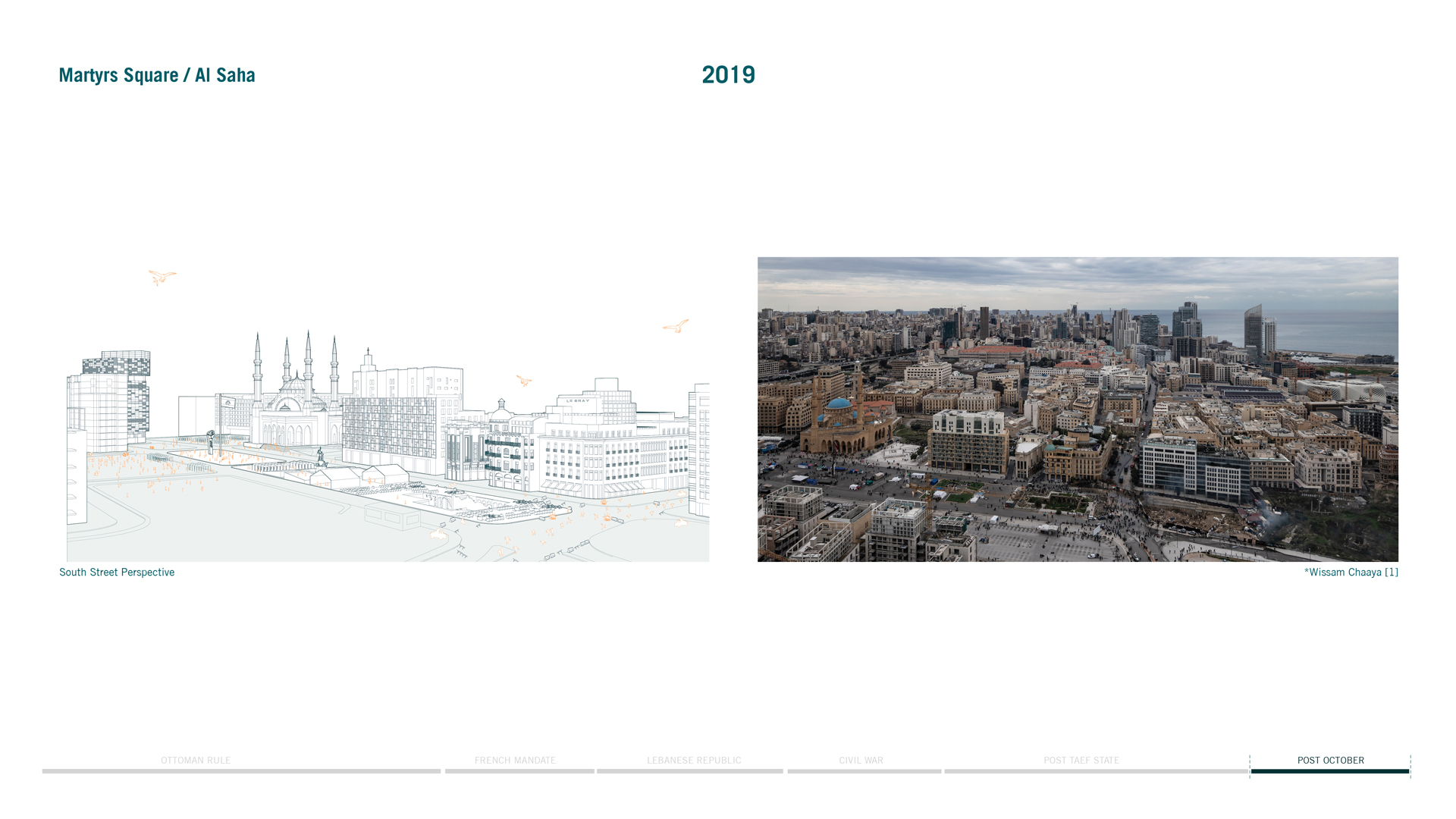

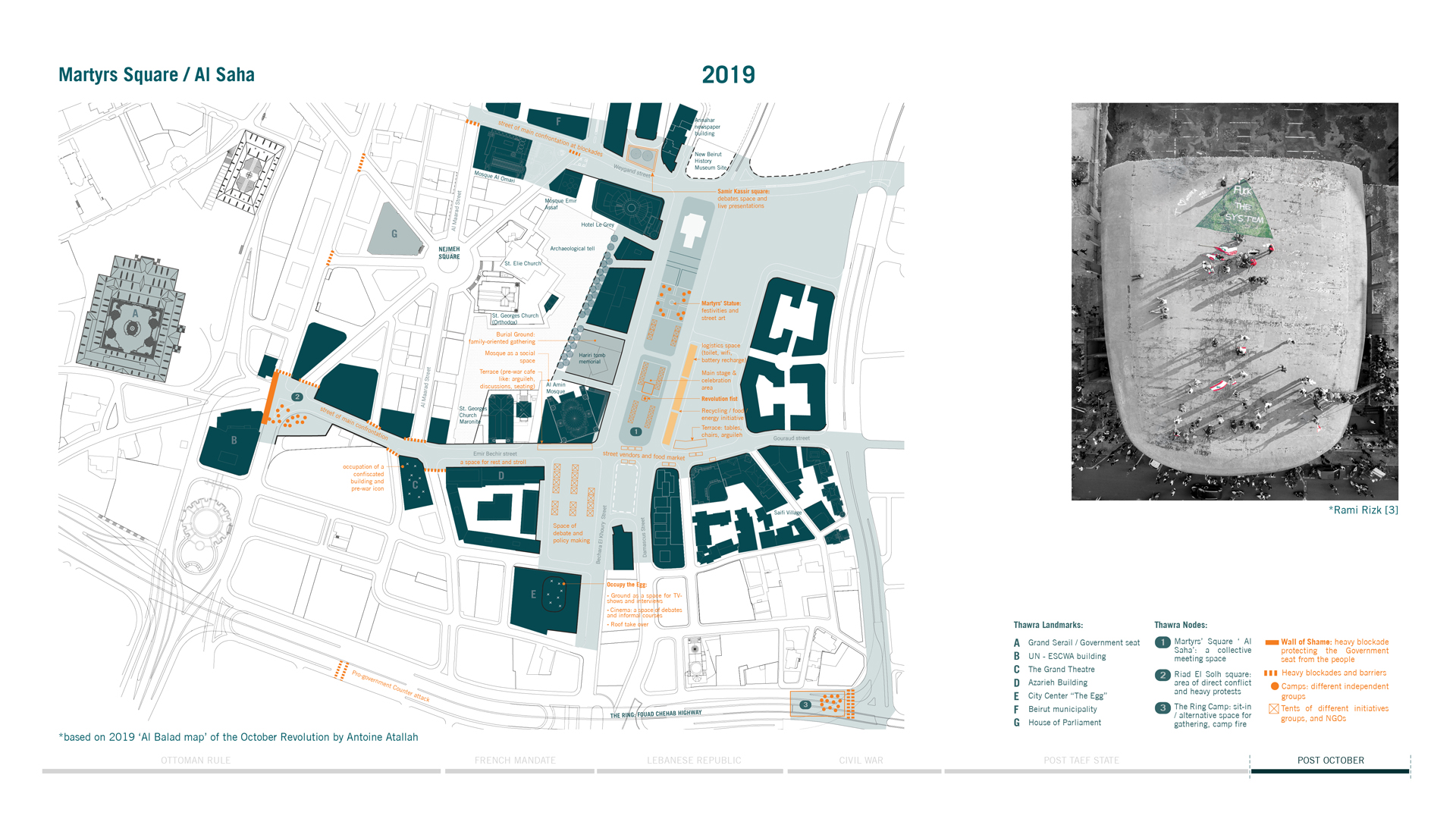

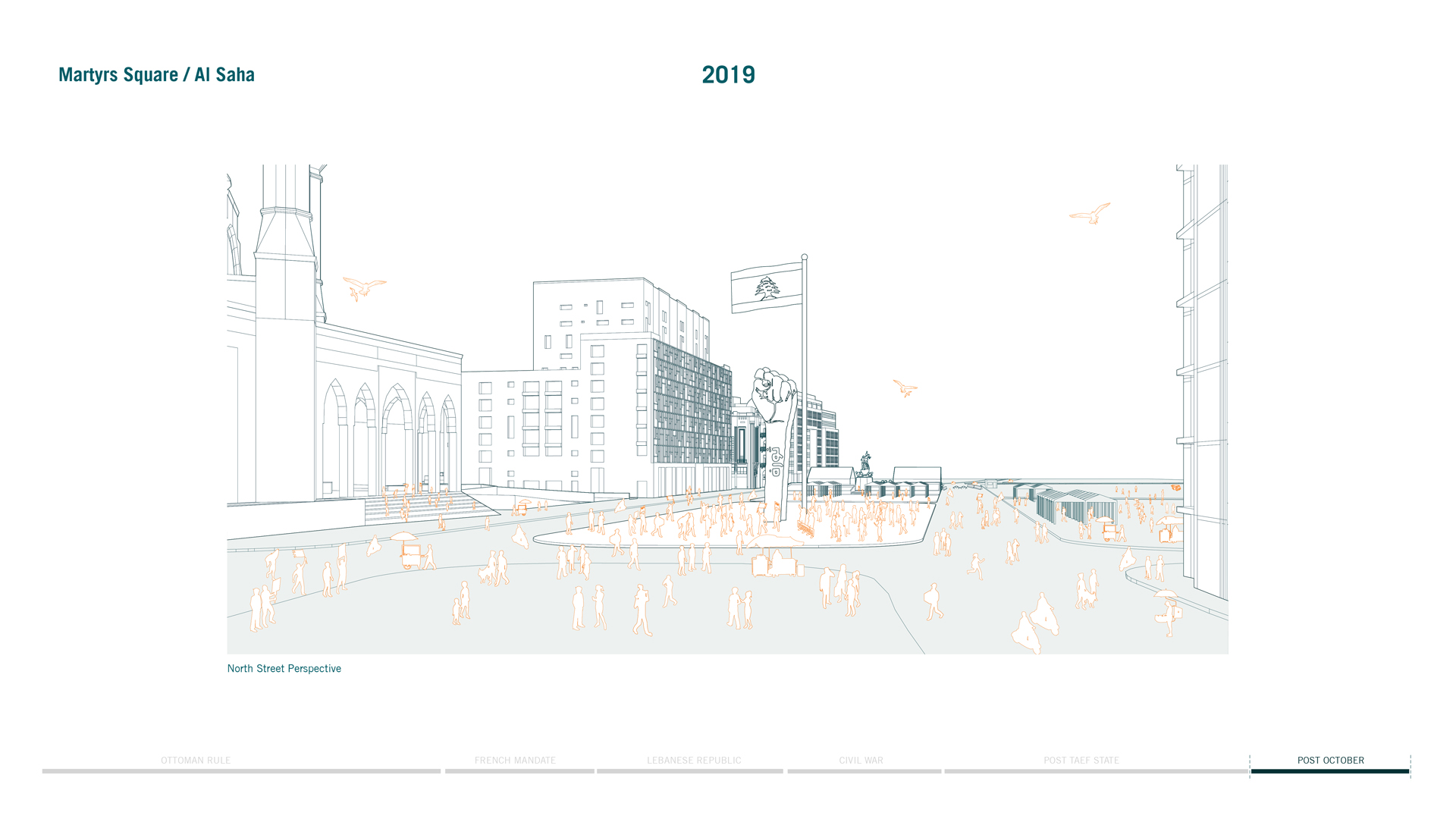

2019- Martyrs Square / Al Saha

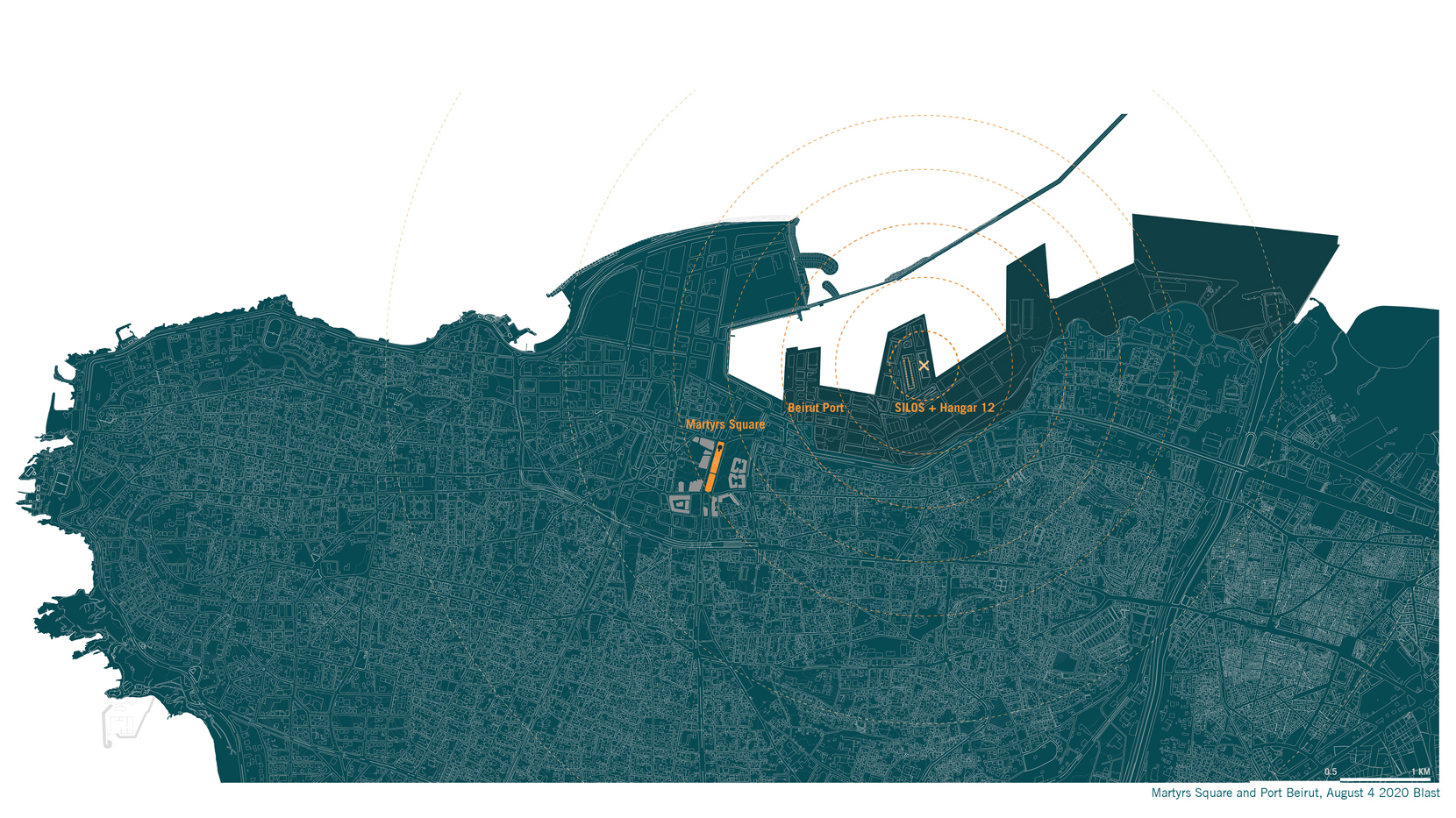

Today’s square, an almost complete real estate project, features high-end developments with privatized ground floors, while it remains a highway junction. After the October revolution, a new spatial transformation emerges, one that takes back the square as a space of collective appropriation – a reclaimed ground by grassroots groups and civil society activists. New informal spaces emerge, from debate areas, independent camps and kiosks, stages for festivities and celebrations, to street vendors and informal markets. Equally affected by the catastrophic blast of 2020, the square as an open field is reinterpreted and re-centralized, from a space of resistance to post-blast relief efforts and gathering grounds.

Free Space for the Collective

In its 180 years of transformation history, the square metamorphosed from a ‘maidan’, an open field utilized as an extramural meeting node and market, to its current state, an open junction and free space that is continuously reclaimed, re-appropriated, and re-imagined by the people.

In its ever-changing forms and boundaries, it has enabled a collective coming together, and a local hybrid identity to be constantly reborn. Despite times of division and conflict, it has retained its significance as a collective ground, projecting forth the necessity of ‘togetherness’ as the only social act that can move us forward.

Credits

Lead Investigator

Carla Aramouny

Carla Aramouny

Production Team

Joseph Chalhoub, Carmen Matta, Lea Tabaja, Rabih Arasoghli, Sarah Tannir, Yasmine Atoui, Ismail Hutet, Mia Baraka, Christina Battikha, Ghinwa Azzi, Michelle Azzi

Support Team

Yara Abdallah, Nour Abdel Baki, Salameh Abla, Lama Barhoumi, Helena Homsi, Careen Matta

Acknowledgments

Archives and Special Collection Department, Jafet Library, American University of Beirut / Sursock Museum Library and Archives / Arab Image Foundation / Solidere / Antoine Atallah / Michael and May Davie / Fadi Ghazzaoui / Rami Rizk / Camille M. Tarazi

*The work wouldn’t have been possible without the support and generous information provided by Fadi Ghazzaoui, Antoine Atallah, Michael and May Davie, and Camille Tarazi. The archives of the Sursock Museum, AUB Archives and Special Collection department, the Arab Image Foundation, and Solidere, provided essential data and photographs to support this production.

References

Gaby Daher (1994), Le Beyrouth des Années 30, Anis Printing, Beirut

Michael Davie (1994), Center and Centralities in Beirut, 1850-1995

Michael Davie (1987), Maps and the Historical Topography of Beirut

May Davie (1996), Bayroût Al Qadîmat: Arab City and Its Suburbs in The Late 18th Century

May Davie (1997), The History and Evolution of Public Spaces in Beirut Central

District, Beirut

Michel Fani (1996), L’Atelier de Beyrouth: 1848 -1914, Editions de L’Escalier, France

Nina Jidejian (1997), Beirut Through the Ages, Dar al-Mashreq

Samir Kassir, Beirut, translation by M. B. DeBevoise (2010)

Samir Khalaf (2006), Heart of Beirut: Reclaiming the Bourj, Saqi Books

Emile Larose (1922), La Syrie et le Liban en 1921. La Foire-Exposition de Beyrouth.

Conférences, Libraire-Éditeur, Paris

Gabriel Rayes, Tania Rayes (2011), Le Centre Ville de mon Pere, Editions de la Revue Phenicienne, France

Farès Sassine, Ghassan Tueni, (2003) El-Bourj. Place de la Liberté et Porte du Levant, Dar an-Nahar Editions, Beirut

Sursock Museum (2014), Regards sur Beyrouth, 160 ans d’Images, Beirut

Michael Davie (1994), Center and Centralities in Beirut, 1850-1995

Michael Davie (1987), Maps and the Historical Topography of Beirut

May Davie (1996), Bayroût Al Qadîmat: Arab City and Its Suburbs in The Late 18th Century

May Davie (1997), The History and Evolution of Public Spaces in Beirut Central

District, Beirut

Michel Fani (1996), L’Atelier de Beyrouth: 1848 -1914, Editions de L’Escalier, France

Nina Jidejian (1997), Beirut Through the Ages, Dar al-Mashreq

Samir Kassir, Beirut, translation by M. B. DeBevoise (2010)

Samir Khalaf (2006), Heart of Beirut: Reclaiming the Bourj, Saqi Books

Emile Larose (1922), La Syrie et le Liban en 1921. La Foire-Exposition de Beyrouth.

Conférences, Libraire-Éditeur, Paris

Gabriel Rayes, Tania Rayes (2011), Le Centre Ville de mon Pere, Editions de la Revue Phenicienne, France

Farès Sassine, Ghassan Tueni, (2003) El-Bourj. Place de la Liberté et Porte du Levant, Dar an-Nahar Editions, Beirut

Sursock Museum (2014), Regards sur Beyrouth, 160 ans d’Images, Beirut

Photograph References

Sursock Museum

[1] Beyrouth - Panorama n°4, ca. 1870-1875, Beirut Lebanon, Albumen print mounted on board (album), Bonfils, Félix, The Fouad Debbas Collection/Sursock Museum. Inv.No: TFDC_118_004_0248.

[2] Beirut, Panoramic view of the old city, no date, Albumin print mounted on board, Bonfils studio, The Fouad Debbas Collection/Sursock Museum, Inv No: TFDC_511_032_SN_01

[3] Place des canons à Beyrouth, no date, Beirut Lebanon, Albumen print, Bonfils Studio, The Fouad Debbas Collection/Sursock Museum. Inv.No: TFDC_511_038_1256.

Library of Congress

[1] American Colony . Beirut. Cafe at the public garden. 1900 [Approximately to 1920] G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2019692682/>.

[2] American Colony . Beirut. Street scene. 1900 [Approximately to 1920] G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2019692681/>.

[3] Beirut. El Burj. Principal city square also called the "Place de Cannon". [Between 1898 and 1946] G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2019703519/>.

Arab Image Foundation

[1] View of the Grand Serail, Photographed by Dr. Eugène Cottard in 1909 in Beirut, Lebanon. Stereograph transparency. 0300co00234pg, 0300co - Dr. Eugène Cottard Collection, courtesy of the Arab Image Foundation, Beirut.

[2] Arrival of General Gouraud at the Place Des Canons

Photographed by Dr. Eugène Cottard in 1920 in Beirut, Lebanon

Stereograph transparency. 0300co00052pg, 0300co - Dr. Eugène Cottard Collection, courtesy of the Arab Image Foundation, Beirut.

[3] Stereograph taken by Aziz Zabbal in 1921 in Beirut, Lebanon

Gelatin silver stereograph negative on glass

0152sa00054, 0152sa - Roberte Zabbal Sawaya Collection, courtesy of the Arab Image Foundation, Beirut.

[4] Celebration of the Lebanese Independence Day at the Place Des Canons. Photographed by Albert Issa in 1944 in Beirut, Lebanon, Gelatin silver developing-out paper print

0089la00014, 0089la - Mansour Lahoud Collection, courtesy of the Arab Image Foundation, Beirut.

[5] Funeral of Selim Takla, Photographed by Mouhieddine Saadé in 1945 in Beirut, Lebanon

Gelatin silver developing-out paper print - 0220ta00281, 0220ta - Youssef Takla Collection, courtesy of the Arab Image Foundation, Beirut.

Archives & Special collection, Jafet Library, AUB

[1] Weeping Women Statue on Martyrs Square. around 1930. Saul Rosenburg Collection. Archives and Special Collection Department, Jafet Library, American University of Beirut

[2] Scene from Martyrs Square –Gifford Doxee. around 1950. Archives and Special Collection Department, Jafet Library, American University of Beirut

[3] Beirut Martyrs Square – around 1950. Gifford Doxee. Archives and Special Collection Department, Jafet Library, American University of Beirut

[4] Martyrs Square - Manoug Alemian Collection. Archives and Special Collection Department, Jafet Library, American University of Beirut

[5] Martyrs Square Statue- around 1960. Manoug Alemian Collection. Archives and Special Collection Department, Jafet Library, American University of Beirut

[6,7,8] Martyrs Square war destruction - around 1990. Manoug Alemian Collection. Archives and Special Coll

Camille M. Tarazi Private collection

[1] Beyrouth. Place des Canons- André Terzis & Fils. Postcard.10 45952- Collection Camille M. Tarazi

[2] Beyrouth. Place des Canons- André Terzis & Fils. Postcard. 10 45967- Collection Camille M. Tarazi

[3] Beyrouth- Place des Martyrs- Photo Sport - 528- Collection Camille M. Tarazi

[4] Beyrouth- Vue aérienne de la place des Martyrs - Jean Gulbenk- M1- Collection Camille M. Tarazi

[5] Beirut- Place des Martyrs- Photo Sport – 91 - Collection Camille M. Tarazi

Michael Davie Private collection

[1] Beyrouth La Place Des Canons. 105. Selecta. Postcard. Michael Davie private collection

[2] Beyrouth, Le Jardin Public, Le Kiosk. 34. Postcard. Michael Davie private collection

[3] Beyrouth Jardin del la Liberte. Postcard. Michael Davie private collection

[4] Beyrouth Place Des Canons. 4. Postcard. Michael Davie private collection

[5] Beyrouth Place Des Canons. Café Parisiana. Postcard. Michael Davie private collection

[6] Place Des Martyrs - Beyrouth. 11. Postcard. Michael Davie Private Collection

[7] Beyrouth Palace Hotel. Photo A. Scavo, Postcard. Michael Davie Private Collection

[8] Cinema Rivoli, Martyrs Square. Postcard. Michael Davie Private Collection

[9] Beyrouth Place Des Canons. 73. Postcard. Michael Davie Private Collection

Baz private Collection

[1] Salim Baz and friend on Martyrs Square. Beirut. Around 1950. Private family photo

Solidere

[1,2] Martyrs square destruction after the war. Around 1990. Photograph courtesy of Solidere

[3,4,5] Martyrs square demolitions and reconstruction. Around 1994. Photograph courtesy of Solidere

[6] Removal of Martyrs Statue for restoration. 1996. Photograph courtesy of Solidere

[7, 8] The square in 2004. Photograph courtesy of Solidere

[9] Virgin Megastore and the square. 2002. Photograph courtesy of Solidere

Aramouny Personal collection

[1,2] Cedar Revolution March 14, 2005. Photographs by Carla Aramouny

Ali Chehade

[1]Flag man video taken during the October Revolution in 2019. Courtesy of Ali Chehade

Rami Rizk

[1,2,3] Photographs taken during the October Revolution in 2019. Courtesy of Rami Rizk

Wissam Chaaya

[1] Panaromic Photograph of the square. 2020. Courtesy of Wissam Chaaya

Louay Kabalan

[1] Photograph taken during the October Revolution in 2019. Courtesy of Louay Kabalan