Architecture / Production

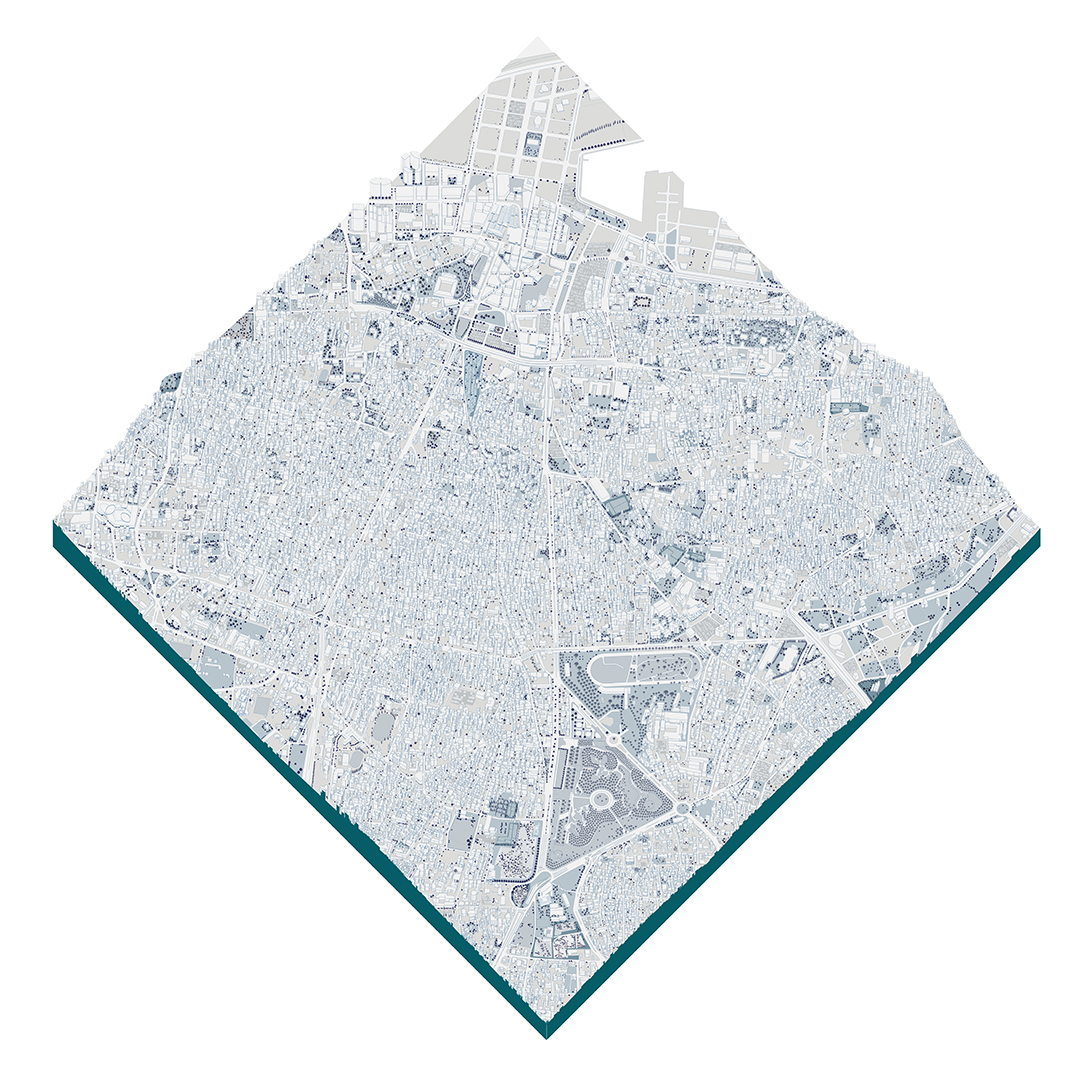

The architecture lens looks at the different architectures and models of development that produced Beirut’s urban ground in the different periods

In a city where the ground has been shaped by its urban architecture rather than by planning, this lens magnifies the architecture of the ground through a comparative outlook of sectional relationships where buildings engage the public ground of Beirut, drawing connections between the regulations that produced them and the type of public grounds they helped create

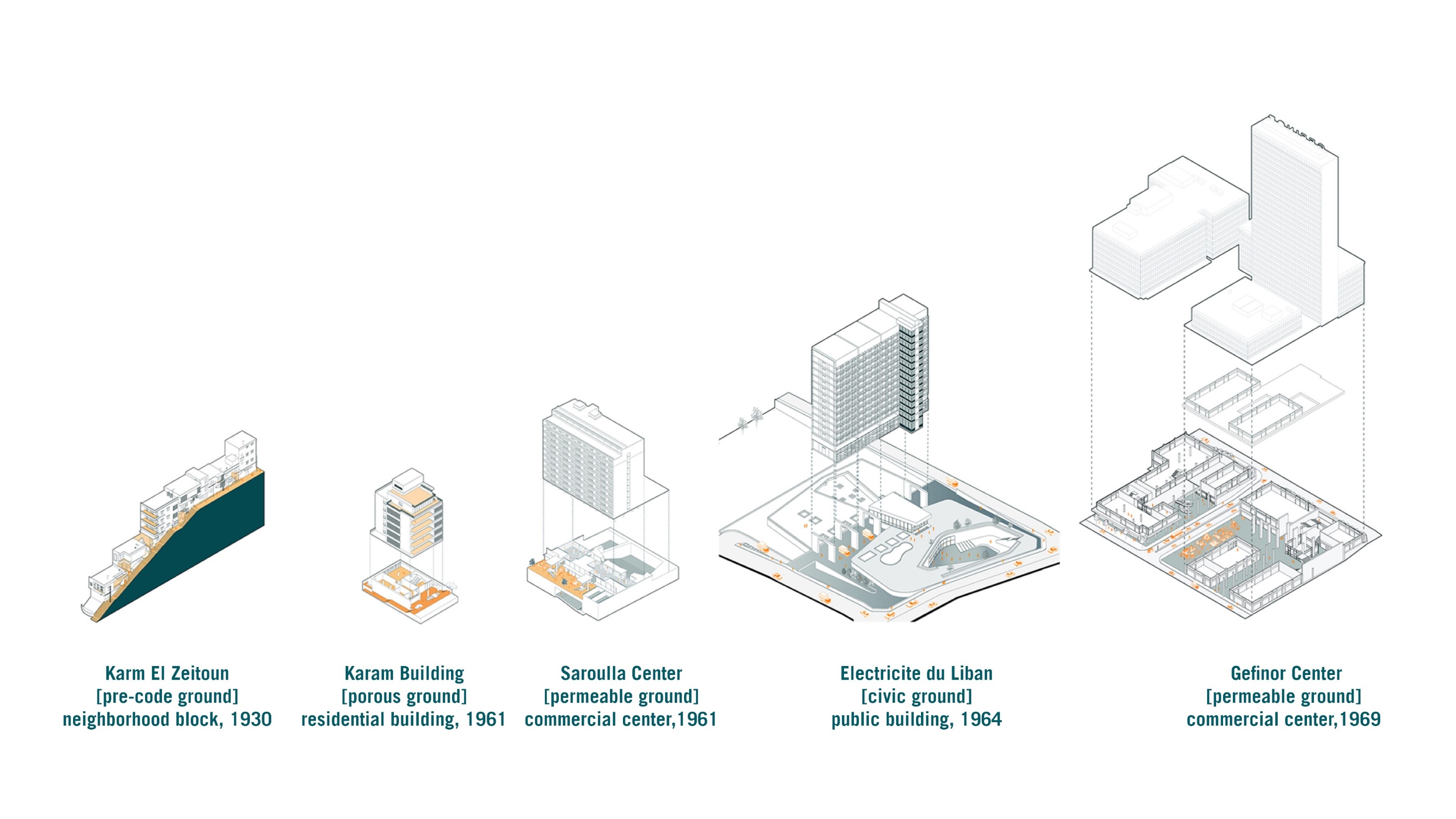

We focus on specific episodes of the ground: Karm El Zeitoun building block as an example of adaptive pre-code ground, Karam Building as an example of porous pilotis ground, Saroulla and Gefinor commercial centers as shapers of hybrid permeable grounds, and EDL building as the epitome of the welfare state period and civic grounds that emerged during the seventies. We focus on pre-code architecture with the urban architecture of Karm El Zeitoun, the residential modernist pilotis building and the ideal of the porous ground, the urban commercial center as a hybrid public realm and the public building as the epitome of the welfare state period.

Through their evolution in the decades to follow- and in times their subversion against their initial spatial premises, we reflect on the modes of production that shaped Beirut in until the Port blast and the need for new bottom up architectural practices.

[1920-1940] the rise of the urban ground

Beirut’s architecture didn’t get a proper building code until the early 1940s. Guided by minimal building regulations throughout the Ottoman and Mandate periods, individual buildings shaped the streets in the burgeoning neighborhoods, led by a skilled scene of master masons and apprentices. Residential urban buildings incorporated commercial street fronts, porous entrances and semi-open staircases that became ground activators and natural extensions of the street space.

Ground 1 | Karm El Zeitoun Building Block

[the pre-code ground]

Neighborhood Block, Karm El Zeitoun

Ground area: 1370 m2

Year: 1930

[the pre-code ground]

Neighborhood Block, Karm El Zeitoun

Ground area: 1370 m2

Year: 1930

The case of Karm el Zeitoun, a neighbourhood created for Armenian new comers in 1930, is a case-in-point of the pre-code architecture and its sensitive adaptation to the ground of the city. The urban morphology of a grid that goes on to meet the topography yielded transversal spines that break and become stairs in the steepest parts. The variation of slopes created a typology of alleyways that adapted today to accommodate various living needs.

Shaped by different types of architectural thresholds and incremental add-ons, the hybridity of public and private results with an urban morphology that is not possible anymore under the current building code.

Shaped by different types of architectural thresholds and incremental add-ons, the hybridity of public and private results with an urban morphology that is not possible anymore under the current building code.

[1940-1971] the hybridized ground

In 1954, a code adjustment removed the maximum height limit of 26 meters, introducing instead the gabarit regulation, which linked the height of the building to the proportion of its parcel. With a lack of specification as to ground implantation, this revision resulted with increased building heights and setbacks in order to go higher; which undermined ground floor alignments and well as streets’ spatial definition.

In 1971, major amendments to the code introduced rules that are largely behind today’s ground: Exclusion of the open areas of the pilotis from the net total of built surfaces, Removal of compulsory fences in the case of setbacks, foregoing street alignments, Additional upper floors on condition of liberating the ground from any construction…

Ground 2 | Karam Building

[the porous ground]

residential building, Badaro

Architect: Joseph Karam

Ground area: 540 m2

Year: 1961

[the porous ground]

residential building, Badaro

Architect: Joseph Karam

Ground area: 540 m2

Year: 1961

The Karam Building was built in 1961, one of many modernist buildings on Alam Street, Badaro. It is characterized as one of the first buildings to introduce the open pilotis ground floor with the intention to extend the sidewalk and the greenery inside and under the building, with an interesting play of materials on the ground, the volumes and walls that make up the pilotis space.

The 1958-1970 period, also known as the welfare state or chehabist period, was a golden age for modern architecture and its engagement with the public realm of the city. Numerous commissions and competitions gave Beirut its modernist landmarks, such as Ministry of Defense, Electricite du Liban and Gefinor Center to name a few. Architecture acquired a public dimension, translated at the ground level(s) of such buildings.

The 1958-1970 period, also known as the welfare state or chehabist period, was a golden age for modern architecture and its engagement with the public realm of the city. Numerous commissions and competitions gave Beirut its modernist landmarks, such as Ministry of Defense, Electricite du Liban and Gefinor Center to name a few. Architecture acquired a public dimension, translated at the ground level(s) of such buildings.

Ground 3 | EDL Building

[the civic ground]

Public building, Mar Mikhael

Architect: CETA

Ground area: 8000 m2

Year: 1965

[the civic ground]

Public building, Mar Mikhael

Architect: CETA

Ground area: 8000 m2

Year: 1965

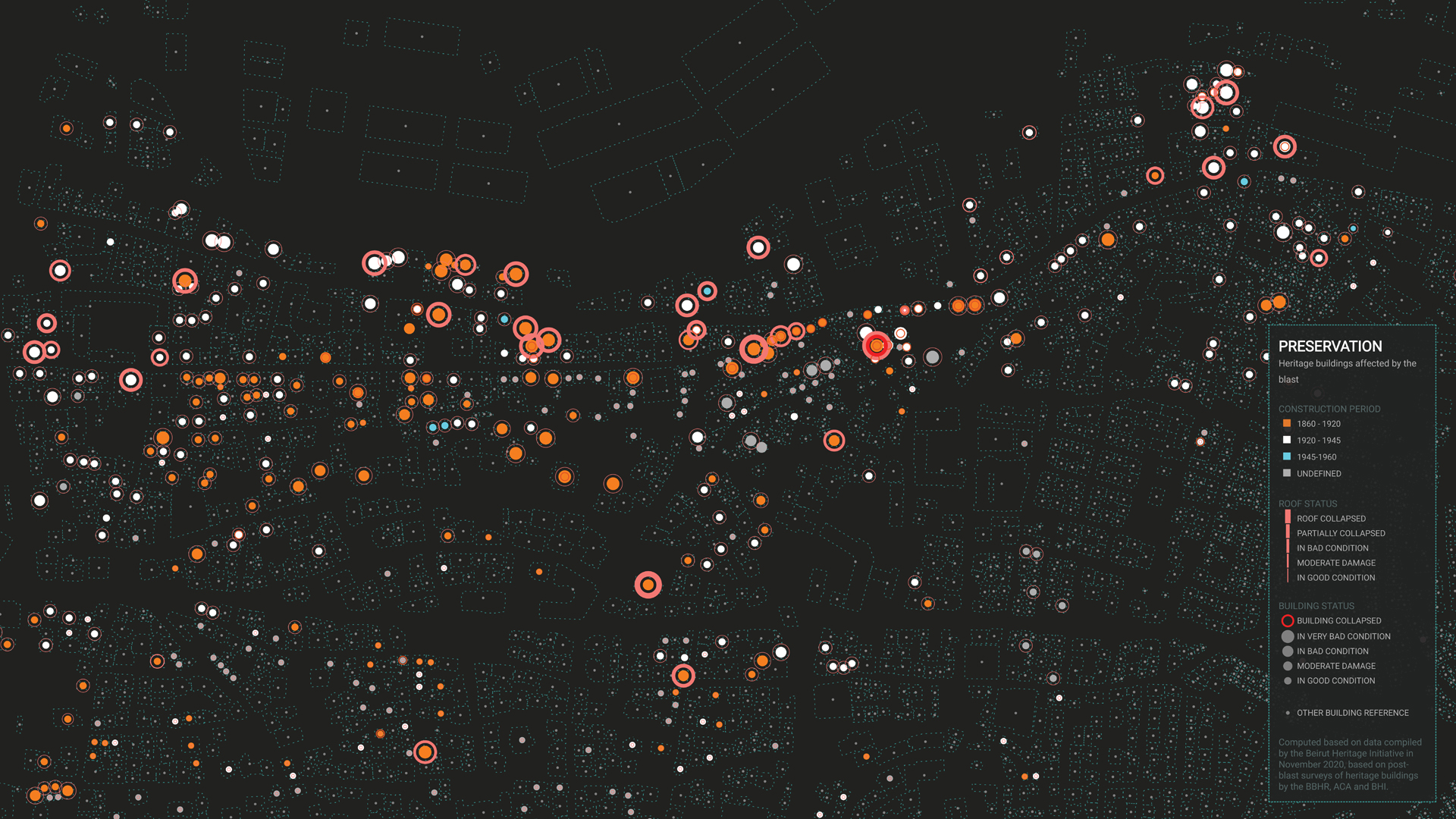

EDL was the outcome of a public competition to host the headquarters of the Electricity company, won and built by renowned architect Pierre Neema and his colleagues Jacques Aractingi, Joseph Nassar and Jean- Noël Conan- also known as CETA. The winning scheme established powerful public realm through its sliding ramp to a lower courtyard, reconnecting through its multileveled ground the inner street fabric to the sea. After the war and in recent period of revolutions, such porosity was undermined by the security mechanisms that were deployed on its ground level, reversing the initial intentions and values of public accessibility the building promoted. The building was shattered due to the Port Blast on August 4th, 2020.

During the sixties, the emergence of urban centers on Hamra street integrated the architectural premise of a porous urban ground, with a clear intention to maximizing the urban/ commercial realm, with the ground acting as a visual and spatial hinge between the urban fabric, street level and upper and/or lower floors. In their golden age, such centers combined the booming entertainment, economic and intellectual life of Hamra and the capital.

During the sixties, the emergence of urban centers on Hamra street integrated the architectural premise of a porous urban ground, with a clear intention to maximizing the urban/ commercial realm, with the ground acting as a visual and spatial hinge between the urban fabric, street level and upper and/or lower floors. In their golden age, such centers combined the booming entertainment, economic and intellectual life of Hamra and the capital.

Ground 4 | Gefinor Center

[the permeable ground]

Commercial center, Hamra

Architect: Victor Gruen

Ground area: 6500 m2

[the permeable ground]

Commercial center, Hamra

Architect: Victor Gruen

Ground area: 6500 m2

When it was built, the Gefinor Center was the largest business and shopping centers in the Middle East.The five blocks, surround a piazza adjoining a street that crosses the complex and joins Rue Maamari and Rue Clemenceau located at different levels.

The architect- Victor Gruen- designed a porous ground with multiple stairs and passages leading from adjacent streets to the main square, contrasting with the typology of “big box” shopping centers that he was building at the same time throughout the world.

Largely due to its location between vital medical hubs, its programming and its architecture that facilitated pedestrian flows between different commercial nodes, Gefinor never experiences the decline of its 1960s counterparts on Hamra Street or Downtown. It remains to this day a vibrant center that gained value with age.

The architect- Victor Gruen- designed a porous ground with multiple stairs and passages leading from adjacent streets to the main square, contrasting with the typology of “big box” shopping centers that he was building at the same time throughout the world.

Largely due to its location between vital medical hubs, its programming and its architecture that facilitated pedestrian flows between different commercial nodes, Gefinor never experiences the decline of its 1960s counterparts on Hamra Street or Downtown. It remains to this day a vibrant center that gained value with age.

Ground 5 | Saroulla Center

[the permeable ground]

Commercial center, Hamra

Architect: Karol Schayer

Ground area: 1500 m2

[the permeable ground]

Commercial center, Hamra

Architect: Karol Schayer

Ground area: 1500 m2

The Saroulla Center was built in 1961 by Karol Schayer. Saroulla was one of the few centers that retained its architecture and vibe after the war, due to the decisions of its owner. Turning down more profitable options of renting the first three levels to an outlet store, he rented the ground to Dunkin Donut coffee shop in exchange of supporting a less commercial counterpart, Gilad bookstore, and rented the former Saroulla cinema to Al Madina Theater, in exchange of renovating the space. Supported by the pop up restaurant of Kababji, the center’s ground was the nexus of a renewed street life for the past three decades.

[1971-1990] the discordant ground

The 1992 amendments to the building code introduced the increase of compulsory cars per residential units and with mandatory parking, and the parking ramp as a marking element on the ground floor. The new regulation forfeited corners situations, rhythm, spatial and pedestrian continuity in favor of optimum column spacing for underground car parking. As a result, the street became a space of traffic, putting cars first and prioritizing vehicular access over human-friendly entrances. Ground floors featured an assemblage of spaces with discordant adjacencies: random storefronts, terrain vague of unbuilt properties, giant retaining walls, prestigious entrances, illegal plug ins, parking ramps…

[2004-2020] the privatized ground

The 2004 law amendment removed porosity between building and street by legalizing the enclosure of balconies with curtain glass, further 25% increase in development on large parcels, that allowed developers to take advantage to push their own interpretations. The ground become linked to the number of sellable square meters, to the number of cars that it can accommodate, to parcels’ merging to result with bigger footprints- and increased height/sellable meters… all interpretations were valid, motivated by a single purpose: to make profit.

This triggered a wave of gentrification in the city, that swept through Monot, Gemmayze, Mar mikhael, Badaro, pitting large developments and vulnerable social groups, and draining the city from its residents in favor of foreign investors who can afford luxury properties.

[2020] crisis

The construction spree portrayed the archaic culture that ruled and ruined the city. After the collapse of the economy and the real estate bubble, empty and unfinished projects stand today throughout Beirut as the ultimate representation of this failed system that rested too much and for too long on real-estate investment as a cornerstone for the economy.

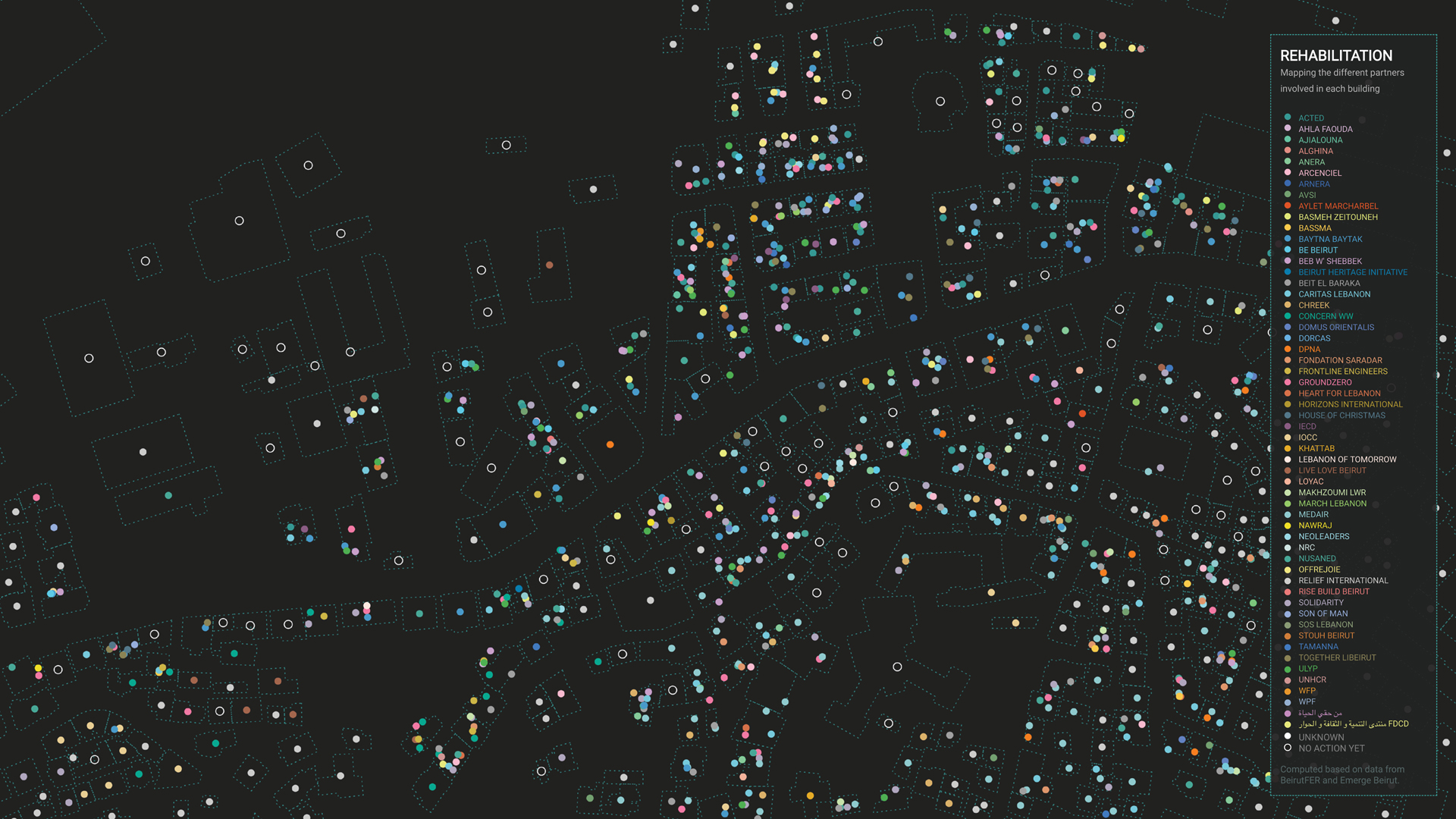

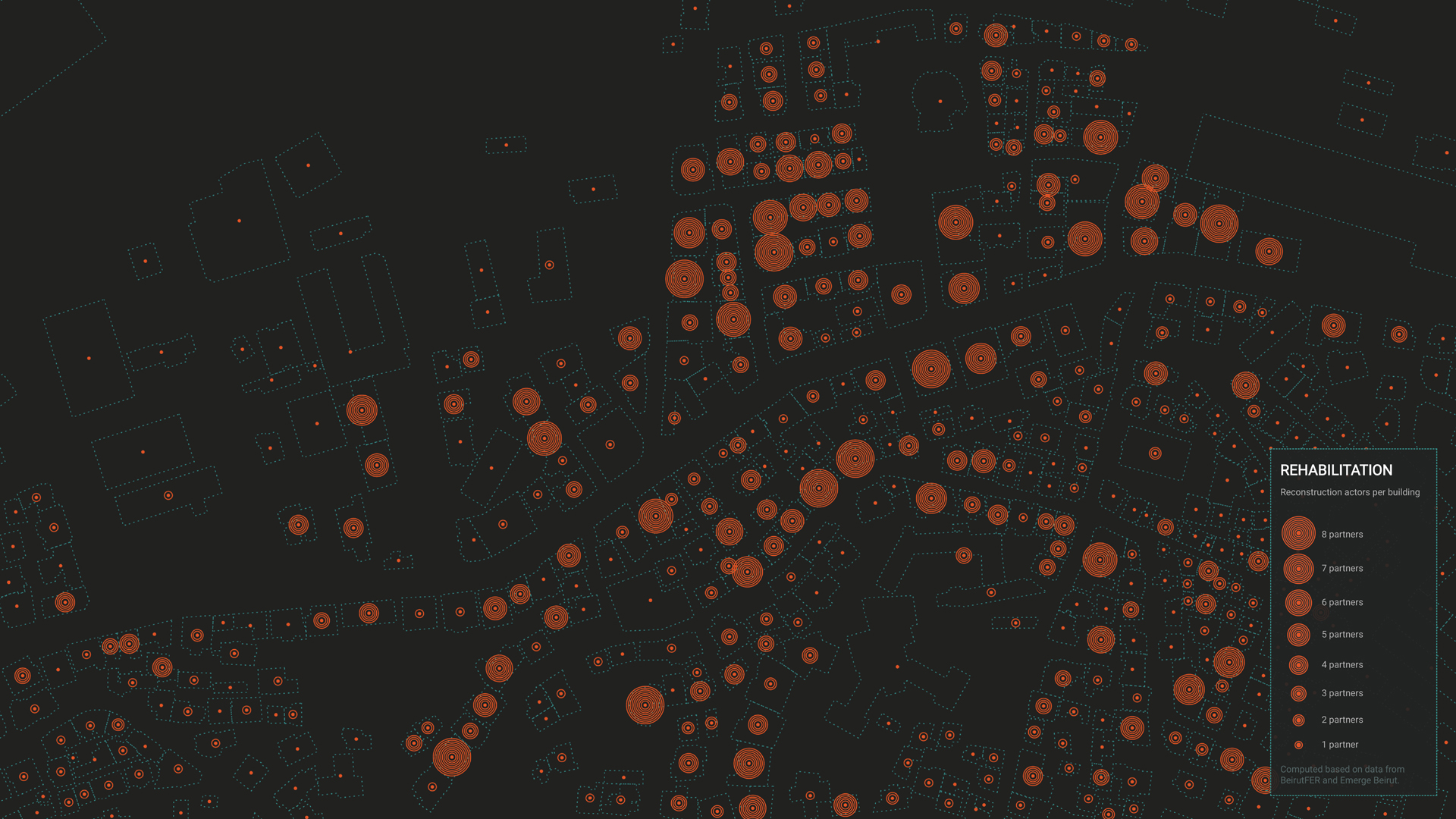

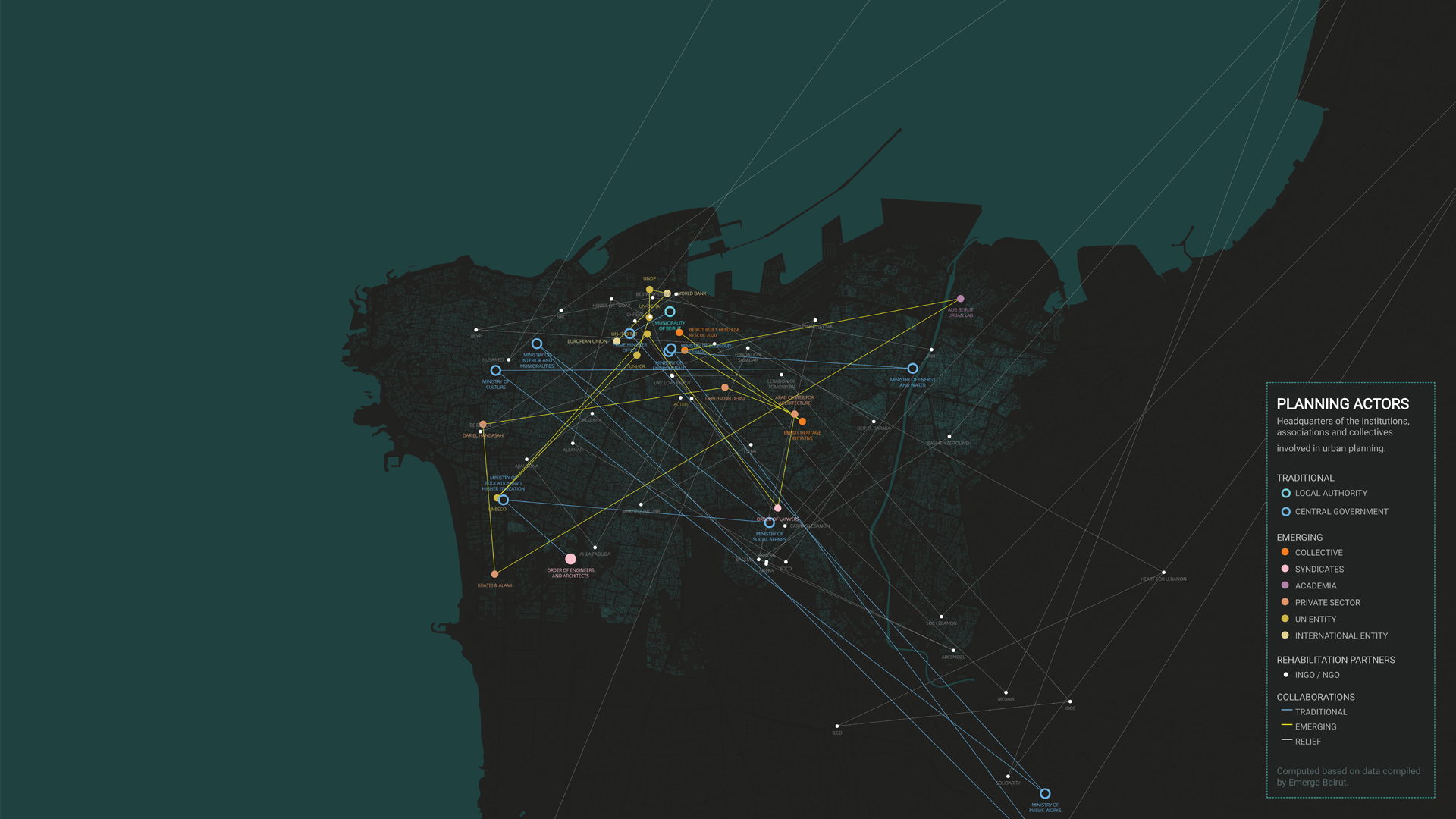

After the Port Blast in August 2020, the reconstruction process showed first and foremost the potential of people, activists, collectives and civil society groups in the production of the city in response to people’s needs.

[2021] collective production

The ongoing financial meltdown brings with it many opportunities. The political and economic changes that led the country to crisis are also the ones that allowed an emerging civic consciousness to challenge sectarian logics and capitalist models of development.

Now that Beirut is starting a new chapter, we propose different ways of inhabiting and reclaiming it, ways that reflect such aspirations and engage its realities.

In such realms, essential infrastructure outlets—water, electricity, data—can overlay the ground and support collective activities and exchanges, like communal kitchens, markets, temporary gatherings, and occupation. Coming from neighborhood-harnessed renewable energies, like rainwater collection and photovoltaics, such outlets can be customized, relocated, and adjusted as needed, and will be the objects of negotiation between the different collectives using it, not unlike the revolution and post-blast deployments.

Now that Beirut is starting a new chapter, we propose different ways of inhabiting and reclaiming it, ways that reflect such aspirations and engage its realities.

In such realms, essential infrastructure outlets—water, electricity, data—can overlay the ground and support collective activities and exchanges, like communal kitchens, markets, temporary gatherings, and occupation. Coming from neighborhood-harnessed renewable energies, like rainwater collection and photovoltaics, such outlets can be customized, relocated, and adjusted as needed, and will be the objects of negotiation between the different collectives using it, not unlike the revolution and post-blast deployments.

With the collective infrastructure serving as a supportive “carpet,” we show multiple possibilities for how the ground floor could transform into an assemblage of amenities that support collective urban life.

Credits

Lead Investigators

Boulos Douaihy

Nicolas Fayad

Boulos Douaihy

Nicolas Fayad

Production Team

Mariana Boughaba, Joanna Howayek, Riad Tabbara, Jana Semaan, Nour Balshi, Careen Matta, Michelle Azzi, Ghinwa Azzi

Image Credits

Wissam Chaaya, Boulos Douaihy, Sandra Frem, Carla Aramouny, Rami Rizk

Wissam Chaaya, Boulos Douaihy, Sandra Frem, Carla Aramouny, Rami Rizk

References

Carla Aramouny, Electricite du Liban building. 2017, Brownbook magazine Issue 66 Aramco World

George Arbid.“Practicing Modernism in Beirut, Architecture in Lebanon 1946- 1970”

Elie El-Achkar. Réglementation et formes urbaines: Le cas de Beyrouth. (Beyrouth: Presses de l’Ifpo 1998)

Robert Saliba. Beirut 1920-1940: domestic architecture between tradition and modernity. (Beirut: Order of Engineers and Architects, 1998.)